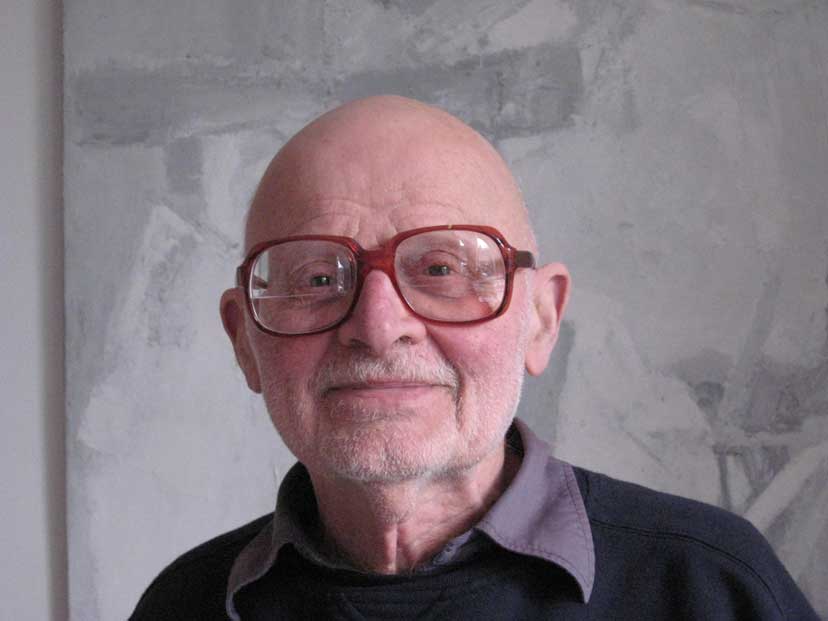

Of the many artists the Dunera bore across the ocean to Australia, none are more well-known for both biting political commentary and atmospheric scenes than Friedrich (Fritz) Schonbach. This article draws from two primary sources to create as comprehensive a picture as possible of this enigmatic artist's life: an oral history, recorded in 1996 by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and a written interview conducted with his daughter Gabriela in late 2019.

Born on 1 July 1920 in Vienna, Austria, Fritz Schonbach (born Friedrich Schönbach) grew up as the only child of a relatively well-off family in what he called an ‘almost suburb’ of Vienna – within walking distance of the city centre. Though years later in Australia, he would switch to using the anglicised 'Fred', his daughter Gabriela writes that he went by many different names over the years, and when he relocated to the US later in life, close friends still tended to call him 'Fritz' or 'Fritzl'. 'I think throughout his life he was trying to accommodate whatever culture and language he was part of,' Gabriela writes. During his time in Buenos Aires, he even sometimes went by Federico. 'He had many identities throughout his life, and each variation of his name seemed to reflect that', says Gabriela. In this article we use 'Fritz'.

Fritz's father, Leo, was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in what is now the Ukraine. He left school early, and ultimately, after leaving the army, was able to build a successful business. Fritz's mother came from Moravia, an area where, according to her son, Jewish communities were better off – ‘one step ahead’ of their counterparts in Poland and Russia when it came to acceptance within the wider, non-Jewish community. His mother was not particularly religious, and while his family tried 'half-heartedly' to give him a religious upbringing, it never really took hold.

As a youth, Fritz attended a private school that catered to a large proportion of the Viennese Jewish community, which may have been the reason why he didn’t feel that Jewish students were treated differently. Though Fritz remembered only one Jewish teacher at the school, the sheer number of Jewish students likely meant that the school couldn't afford to discriminate against Jews and so alienate a large part of its community.

That was in stark contrast to the wider Viennese community. In the 1996 interview, Fritz said anti-Semitism was a given in Vienna at that time and ran very deep in Austria. In spite of the superficial friendliness among the upper classes, Fritz doubted this camaraderie reflected how people felt deep down. From reading the papers to incidents in the streets, there was ‘hardly a time I remember where there were not at least verbal assaults from people on the train’.

Immediately after the Anschluss – the Nazi takeover of Austria in 1938 – Fritz's parents realised they had to get him out. ‘We knew enough of what had happened in Germany to Jews and political opponents to want to leave immediately’. 'Dachau', one of Nazi Germany's first concentration camps, had by then already become almost a generic term for a concentration camp, and Fritz was aware of its existence from the time he was about 14, in 1934.

Fritz's parents managed to secure him passage to a Swiss school, and though his documents weren't entirely in order, luck was on his side when he went to cross the border. He passed along a tiny train track, and the Austrian border official didn't examine his documents closely, telling him only to hurry on his way. Fritz studied in Switzerland for one year, passing the Oxford School Certificate in just a couple of months, and later joined his parents in Italy. Through friends he managed to obtain a visa for Britain, and one month before the outbreak of the Second World War, found himself alone in London.

A series of Schonbach cartoons highlighting how much life changed for the men interned and sent away aboard the Dunera.

A series of Schonbach cartoons highlighting how much life changed for the men interned and sent away aboard the Dunera.

His time in London was lonely. When war broke out, he was forbidden from taking any work, and not long after was denounced by his landlady, who had heard him speaking German to a Jewish refugee in a neighbouring building. He was hauled before a tribunal and categorised as ‘to be interned if the need arises’. His good command of the English language unexpectedly worked against him. Why would an Austrian be able to speak English so well if not for nefarious purposes? One of the most painful things for Fritz was the extent to which people did not understand his situation and that of his fellow refugees. To them, he was just another German speaker from Vienna: what was he doing outside his country?

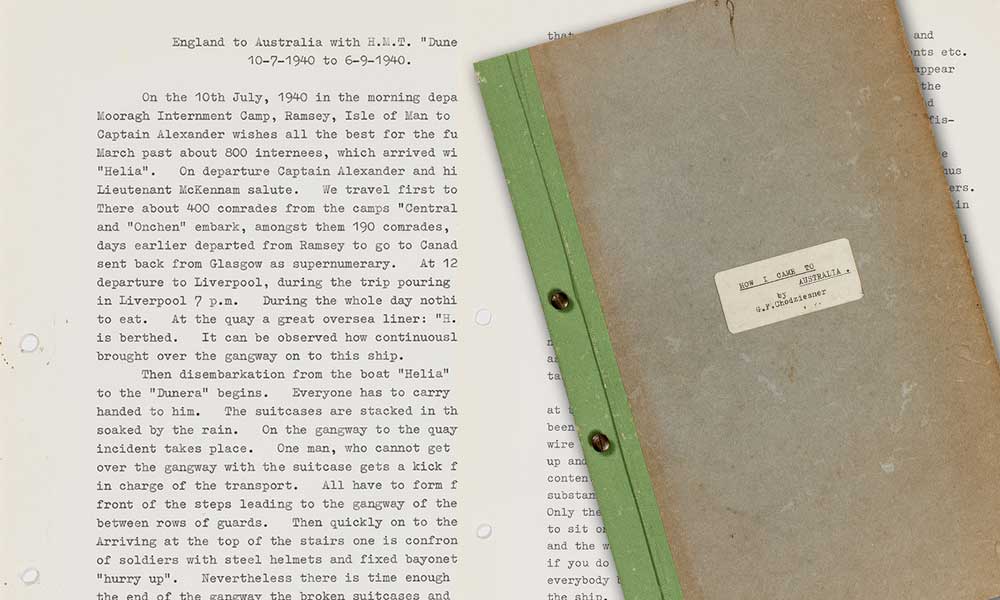

A drawing done aboard the Dunera.

A drawing done aboard the Dunera.

After being interned, Fritz was moved to several sites around London, including Kempton Park and Lingfield Racecourse. On 10 July 1940 he arrived at Liverpool, along with 2,546 other male internees. There they boarded the Dunera and, in spite of the terrible conditions on the ship, he was able to pursue his love: drawing. From a young age, Fritz had wanted to be an artist – a caricaturist. This was not the future his parents had in mind for him: they believed that artists didn't make a living and went hungry. But on a ship of refugees, that didn't matter. He rescued a pencil stub from the pile of things taken from him when he boarded the Dunera, and used it to draw caricatures on the long table in his section of the ship. He drew life on the ship: fights in the latrines; the sleeping quarters; and his fellow refugees exercising.

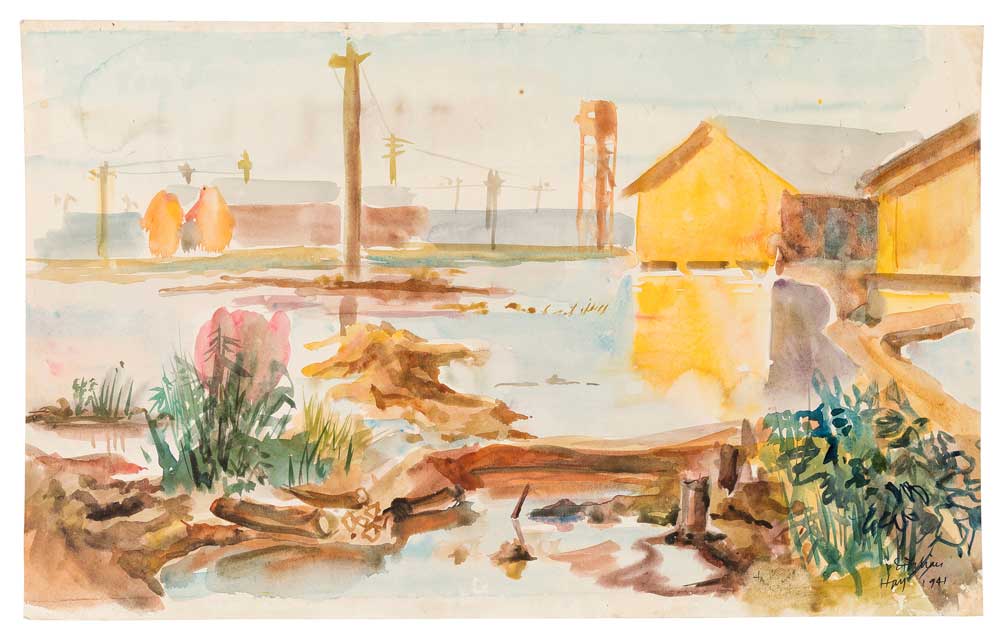

After the ship arrived in Sydney, Fritz and his fellow internees were transported by train to Hay, a remote town in western New South Wales. In camp 8 at Hay, Fritz, along with a few other internees, started a newspaper, Der Lager Spiegel (The Camp Mirror). And in the camp, with more access to materials, he continued to do caricatures and to sketch: reminiscences of the journey on the Dunera, documentation of Julian Layton's 1941 visit to Hay, and bird’s eye views of the camp. He even started to sell his work to some of the older, wealthier inmates. Many years after the war, he met with the sons of one of these men, who treasured these drawings as much as their father had; one man even returned one of his old drawings to mark the occasion of their meeting.

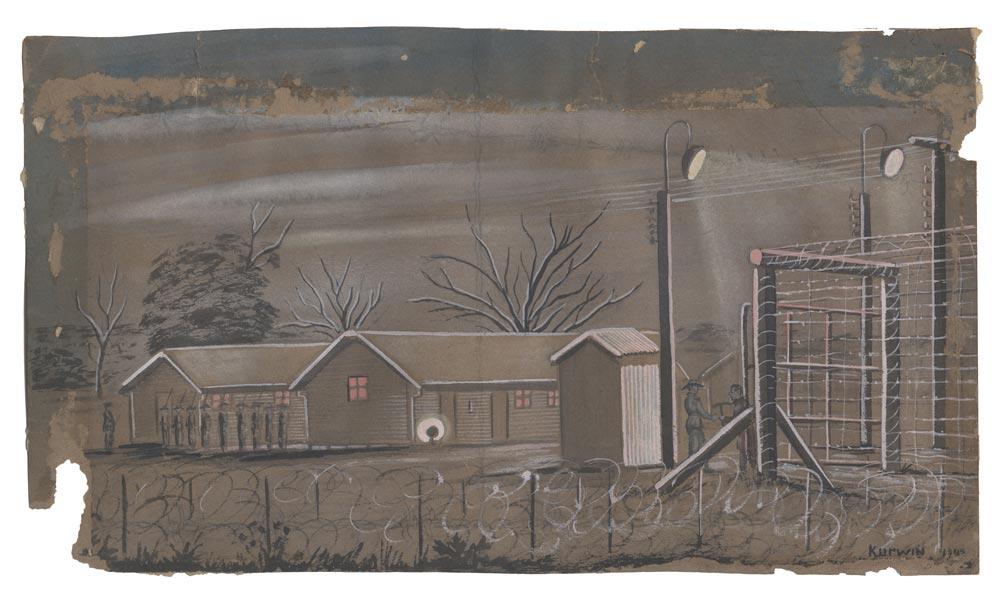

One of Schonbach's well-known bird’s eye view drawings.

One of Schonbach's well-known bird’s eye view drawings.

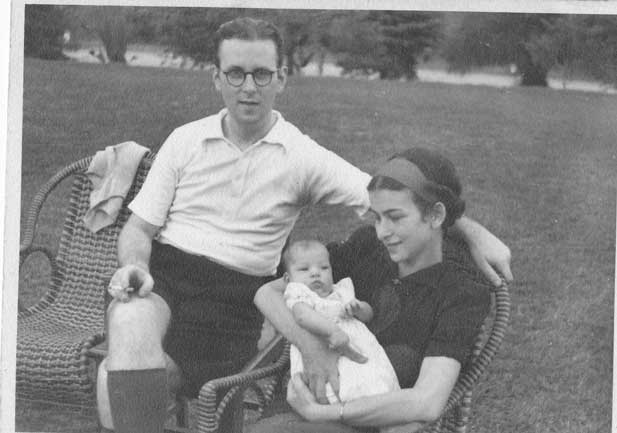

Like many other Dunera internees, Fritz joined the 8th Employment Company, and was able to start publishing cartoons in small newspapers. Fritz was ‘hooked’: ‘when I got out of the army, I wanted to be a cartoonist’. On demobilisation in 1946, he wasted no time in relocating to Sydney, where he enrolled in East Sydney Technical College through the Commonwealth Reconstruction and Training Scheme. During his studies there he met his future wife, June Heydon. Their daughter, Gabriela, says that her parents met at a locale frequented by Sydney students at the time. Fritz ‘caught sight of my mother across the room, and her beautiful smile and deep-red coloured hair captivated him.’ At the time, June was an apprentice to a photographer, which meant she and Fritz had a shared interest in art.

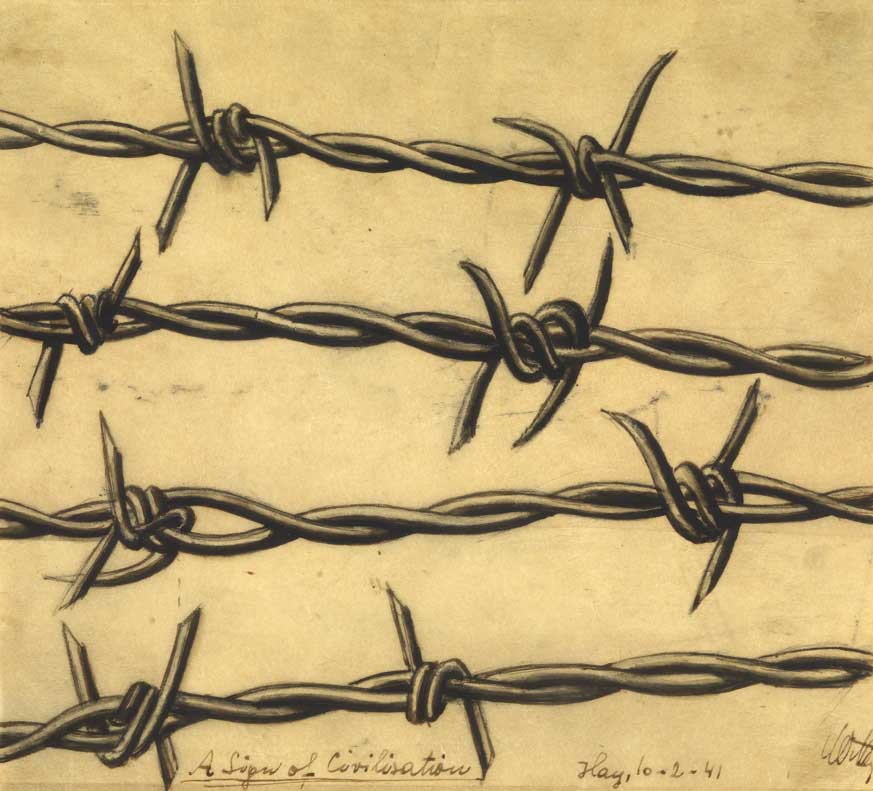

A sketch about release. Finally, the internee is on the other side of the barbed wire.

A sketch about release. Finally, the internee is on the other side of the barbed wire.

Gabriela says that, unlike many, her father was quite open about his wartime experiences. He shared many stories with his children. ‘You could tell,’ she writes, ‘[that] there was an underlying sense of anger around having been forced to flee and then being betrayed by the Austrians and the British. He had a lot of contempt for how the Austrians had welcomed Hitler into Austria’. This anger was, however, tempered by an optimism, an openness to adventure, to new experiences, a love for life.

An illustration done by Fritz for a 1948 issue of Home Fortnightly.

An illustration done by Fritz for a 1948 issue of Home Fortnightly.

After Fritz finished his degree, he and June made their way to Europe, where they hitchhiked across the continent. They ended up in London, where they spent a few months living with a cousin and attempting to piece together an income. At the end of 1950, Fritz's father – desperate to see his son after more than a decade – sent boat tickets to him and his new wife, and Fritz and June arrived in Buenos Aires in 1951. They lived there for the next eight years.

When Fritz was able to find work in Buenos Aires, it often involved illustrating book covers.

When Fritz was able to find work in Buenos Aires, it often involved illustrating book covers.

In the 1996 interview, Fritz remembers life in Buenos Aires as difficult, saying that though he was able to sell some illustrations – including some for book covers – he never made a decent living. Yet it was still a time of vibrant creativity. He sketched Buenos Aires street scenes, facades, dock workers and even returned to his old favourite – the bird's eye view.

A bird's eye view of a Buenos Aires park.

A bird's eye view of a Buenos Aires park.

Gabriela's own memories of this time are quite different. While she acknowledges how hard it must have been for her parents, her memories of Buenos Aires, as a carefree four-year-old, are almost all happy. She remembers running around the city with only her five-year-old brother for company. ‘Hard to believe now,’ she writes, ‘but we were very safe’. The family spent summers by the sea in a tiny beach town called Villa Gesell. For Gabriela, ‘being yanked out of the middle of summer in Argentina and [landing] in a bleak and cold foreign country’ was a rude shock. After eight years in Buenos Aires, Fritz and June decided to move to the US. Fritz left first in 1959, and his family followed not long after. They eventually settled in Washington, DC, where they remained for many years. Towards the end of his life, Fritz and June made one final move: to Canada, to be closer to their daughter, Gabriela, and their granddaughter.

An illustration done in Vancouver, Canada, 1993.

An illustration done in Vancouver, Canada, 1993.

Fritz never spoke German to Gabriela and her brother, but they attended a German kindergarten, and her grandparents spoke German to her when she was young. In high school, she was able to spend a month living in Vienna with her grandparents and studying German intensively at the University of Vienna. This was not her only trip to Vienna: the previous year she had made the trip with her father. She remembers ‘playing bridge with my grandfather and his friends, in German. It was a wonderful experience.’

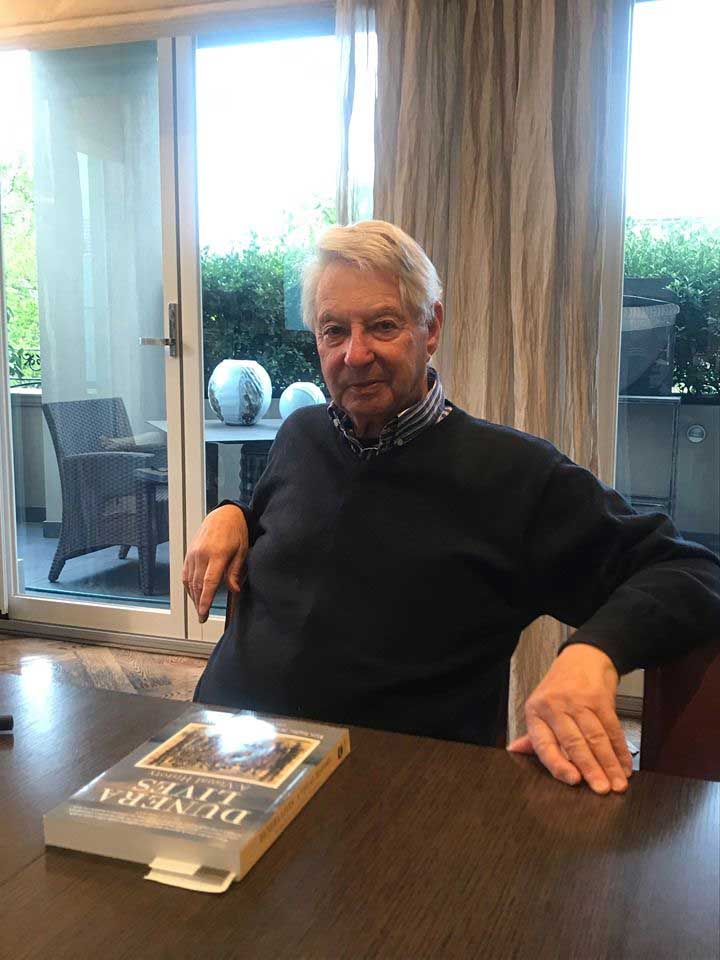

Fritz returned to Australia later in life, attending the 50th Dunera anniversary reunion at Hay in 1990. Gabriela says he enjoyed the experience immensely. Fritz had stayed in contact with a number of friends, both from camp and from art school in Sydney. His closest friend from that time was Klaus Friedeberger (1922-2019), a fellow Dunera boy and artist, who went on to make a name for himself in the world of abstract painting. ‘When my father died,’ writes Gabriela, ‘I viewed Klaus as the closest living person to stand in for him because he had such a similar story’. Over the past decade, Gabriela has been a frequent visitor to Klaus's London home.

Gabriela now works as a producer in the film industry, and has long been playing with the idea of creating a film based around her father's – and mother's – lives and experiences. She would love to explore his life across several continents, his journey with June – ‘and of course the art!’ Art was Fritz's way of existing in the world, and Gabriela writes that he never ‘separated himself from his art; he was always sketching and 'arting' as he would say’; he was an observer and a recorder.

There is much art and many memories to sift through and Gabriela is, by her own admission, very busy. Asked why she thinks her father's story is important, she writes: ‘even though it's a footnote in history, it's important to our family's history. All stories of the Holocaust and the diaspora of the Jews are important to record.’ Australia benefitted greatly from the men who chose to stay, and she notes how grateful she is that Australia is paying attention to this story. ‘History is under attack,’ she writes, ‘and we can't forget the past.’

All images © The Schonbach family

Author: Kate Garrett