Aboard the first Kindertransport to depart Germany for Britain, Peter Danby (formerly Danziger) could not have known the unlikely journey ahead.

Peter was born on 16 January 1923, the son of a grain merchant. He grew up in Rostock, Germany, on the Baltic Coast. The year before his departure to Britain, his parents had sent him to Berlin, to work in a carpentry workshop – 'sound planning,' observed his friend and fellow Dunera boy, Bern Brent: 'For a young immigrant abroad, this [experience] was far superior to have than the piece of paper certifying completion of high school'. This background would lay the groundwork for Peter's future in Australia.

On his arrival in Britain, Peter worked as an apprentice carpenter. It was during his time in Sutton that he first met Bern, to whom he would remain close for the rest of his life. In his autobiography, Bern remembers Peter as a 'stocky, fair-haired Pomeranian peasant type… [with] a ready laugh and an earthy hob-nailed kind of charm'.

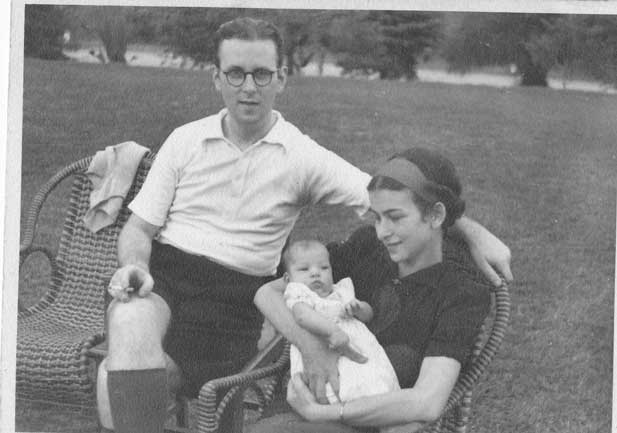

Bern Brent and Peter Danziger, c. 1946-1947. (Image: Bern Brent)

Bern Brent and Peter Danziger, c. 1946-1947. (Image: Bern Brent)

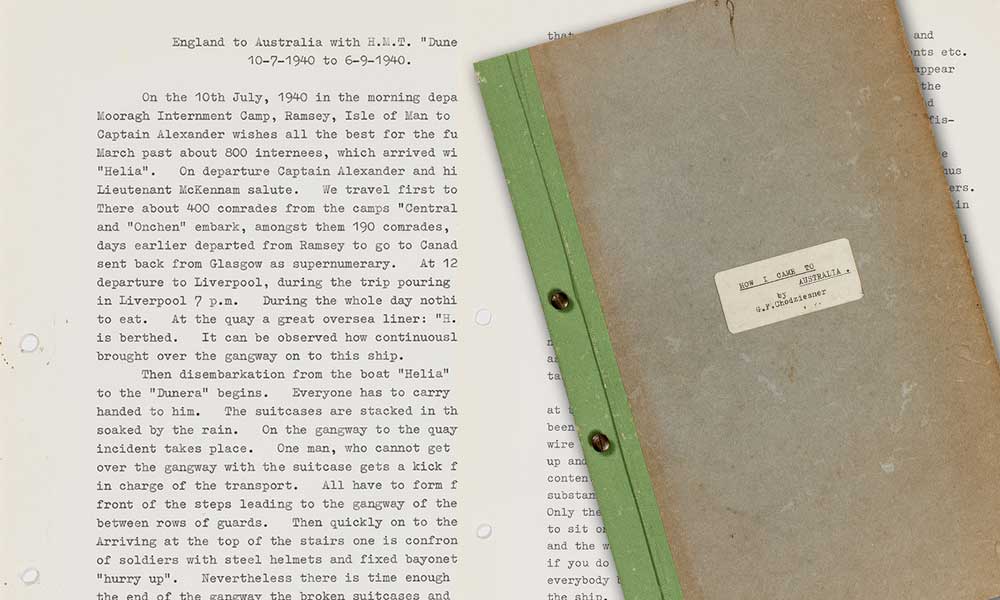

Indeed, it was Peter who Bern credits with convincing him to board the Dunera and make that fateful journey. Though at the time they did not know where the ship was headed, Peter hoped for Australia, where his brother – Kurt Joachim Danziger, later known as Fred – lived. Unlike most other Dunera boys, Peter and Bern volunteered to make the voyage. The Dunera sailed on 10 July 1940. Peter was just 17.

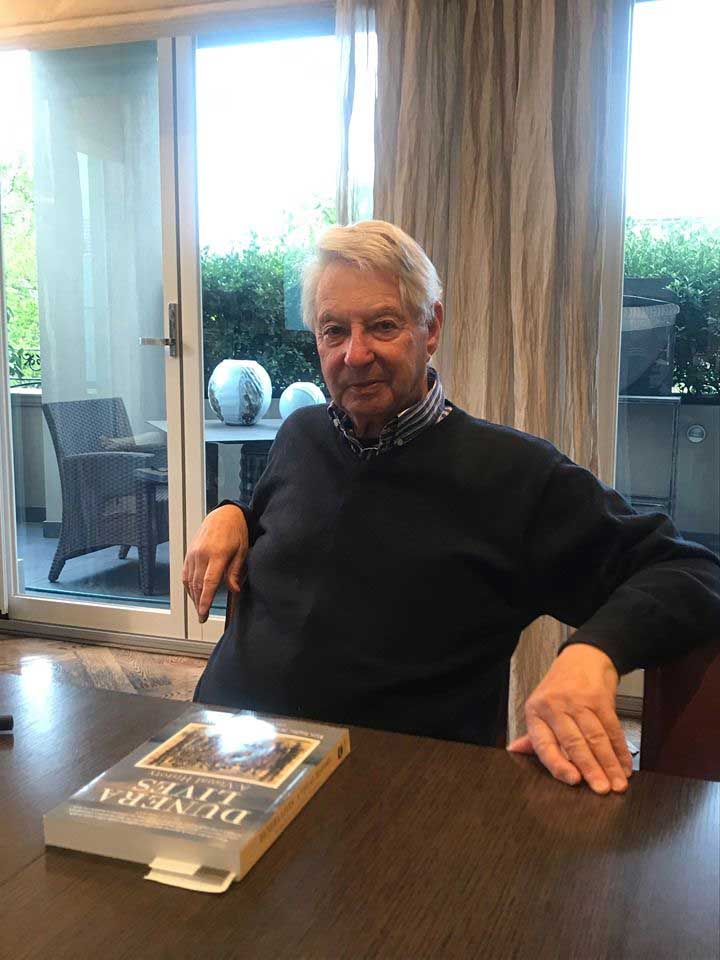

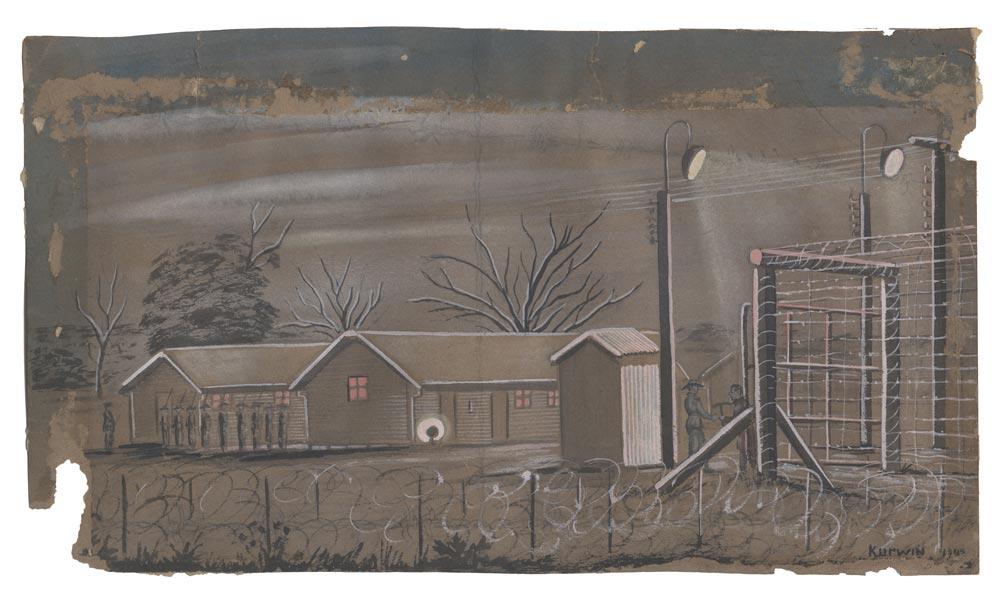

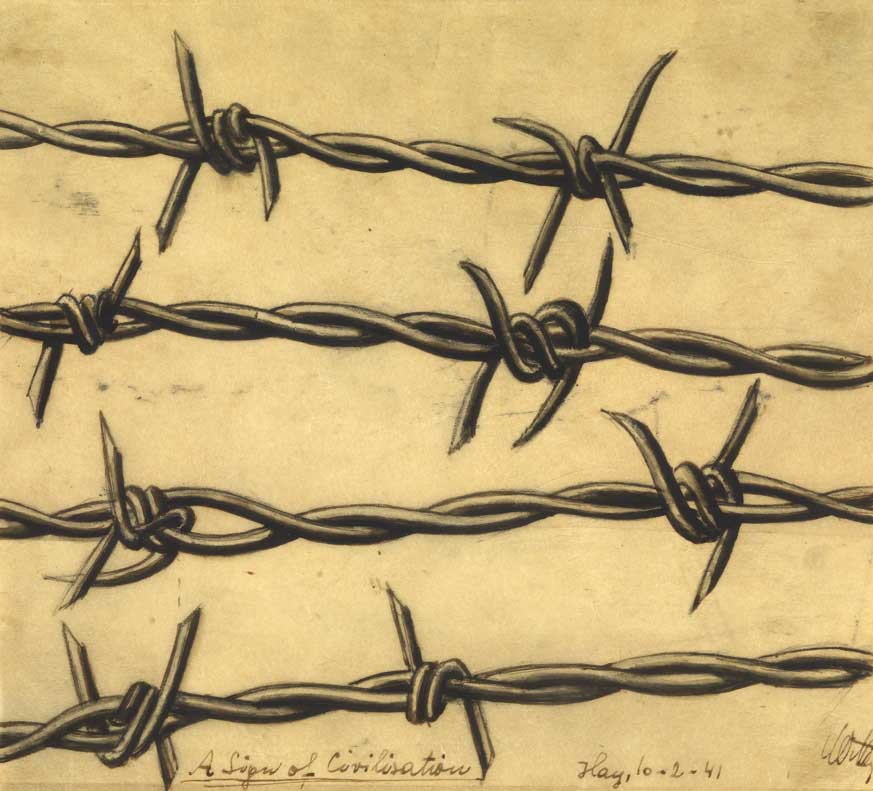

Peter’s files at the National Archives of Australia tell the story of his Australian internment. He was ‘marched into Hay’ on 9 September 1940. In May 1941, he was transferred to Tatura, where he lived for the next eight months. Like many of his fellow internees, including his friend Bern, Peter was released in January 1942. He picked fruit before joining the 8th Employment Company of the Australian army that April.

Peter Danziger after joining the 8th Employment Company. (Image: Bern Brent)

Peter Danziger after joining the 8th Employment Company. (Image: Bern Brent)

Peter's gamble paid off: he was reunited with his brother, Fred. Having arrived in Australia in 1939, Fred had been classed as a 'friendly enemy alien' when the war broke out and was permitted to join the military. Michael Danby, Peter's nephew, speaks of the many endearing letters Peter sent Fred while still interned.

The brothers later would learn that their parents had been deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered in the final days before the camp was liberated in January 1945. When we speak to Peter’s son Gary at the Danby factory in Surrey Hills, Melbourne, he shows us photos of his grandparents’ former home in Rostock and of the 'Stolpersteine' in front of it that bear their names: Bruno and Margarethe Danziger.

After joining the 8th, Peter was stationed at Caulfield racecourse. It was during this time that he met his future wife, Cipa Brott, at a dance for Jewish soldiers at the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation. They were married in 1946; Bern, Peter's friend from his days in England, was his best man.

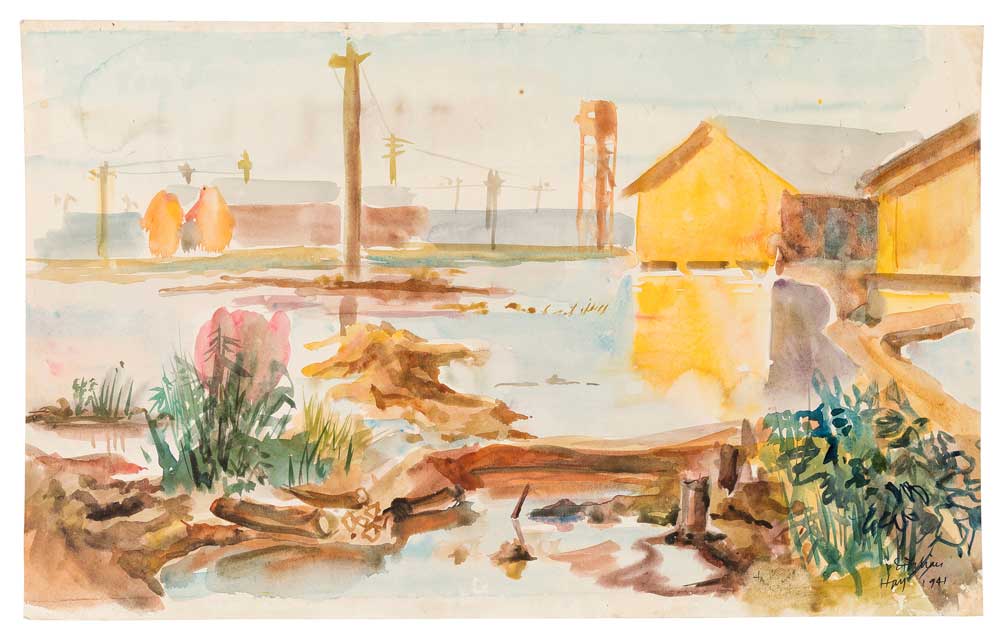

While Bern opted for university at the end of his military service, Peter returned to his pre-war training. With a loan from his wife's family, he purchased a former hay loft in Surrey Hills, then on the outskirts of Melbourne. It became the company's operations base for decades, and from the beginning, the focus was on interior fittings and contract furniture. Though Peter's son, Gary, has long since taken over the business, all the buildings in the factory complex still bear his father's name.

Peter's factory in the 1960s.

Peter's factory in the 1960s.

Peter remained in Australia for the rest of his life, becoming a citizen and adopting many Australianisms. But he never forgot the difficulties of finding work in a new country. Gary fondly recalls his father going to the Melbourne docks and recruiting immigrant labourers straight off the boats, offering them work at his Surrey Hills factory.

Peter's was a truly international workforce, with workers from Australia and all across the globe: from his homeland of Germany, Italy, Vietnam, the former Yugoslavia, Austria and beyond. Gary tells stories of his father's former employees: a quiet and unassuming Vietnamese man named Can, who was a martial arts expert; an Italian called Rocco Morrelli, who could create the most wonderful things with just an axe; Mario Nanut, who would declare something impossible – only to have that very task completed in a most professional manner the following day. Some of the company’s apprentices went on to earn the title coveted among young tradesmen: Apprentice of the Year.

Peter eventually built a successful business in the post-war boom in Australia, fitting everything from the Royal North Shore Hospital and the Melbourne Hilton's Cliveden Room – now the Pullman Melbourne – to CSIRO offices in Melbourne and Canberra, and the University of Sydney's biochemistry labs. The Cliveden Room, as Peter knew it, is no longer, but other renovations for which he was responsible remain in place across Melbourne and beyond.

After the war, the Dunera boys went their separate ways, making new lives and building futures. In 1968 they came together for their first reunion. The intervening years had done nothing to change Peter's good nature and the easy laugh that Bern remembers from their days in Sutton: according to Gary, Peter was one of those who helped bring everyone together in 1968.

Gary remembers his father as someone who worked hard and played hard. He loved to ski on snow and water , and was an avid golfer, fisherman, sailor and tennis player. With his extended family, he would throw large celebratory dinners, and pink champagne parties on festive occasions. Family was important to Peter, perhaps because of his own childhood cut short. He never stopped missing his mother, whom he last saw when he fled Germany at just fifteen.

Following Peter's premature death in 1973, his wife took over the business with Gary, then a fresh architecture graduate with a one-year-old child. With Cipa and Gary at the helm, the company went from strength to strength, fitting out the Regent Hotel, the 46 floors of the ANZ head office at Collins Place, and many other interiors. Their work in fitting libraries in the High Court of Australia led to the Danby Group being selected as a major contractor in the renovation of the new Parliament House in Canberra. Even now, Gary's company, Danby Contracts, is still involved with Parliament House; it is refurbishing the lift interiors.

Melbourne University labs in the 1960s.

Melbourne University labs in the 1960s.

Gary and his mother Cipa, continued to run the business for many years, with the same drive and vigour of the late Peter Danby. Gary tells me about how Cipa, in her 80s, planted herself in the front office of a non-paying client with a sign saying, ‘this company does not pay its subcontractors’. She stayed in the foyer, telling anyone who entered that the company was refusing to pay. Finally she was paid just to get her to leave.

The Danby family in Australia has grown significantly from the two brothers separated by the war and then reunited halfway across the world. Peter's two children, his son Gary and daughter Peppy, now have children and grandchildren of their own. While Gary's children work in other areas, Peter's legacy lives on in his growing and happy family, and in the offices, labs and libraries across Melbourne and Australia that bear the Danby mark.

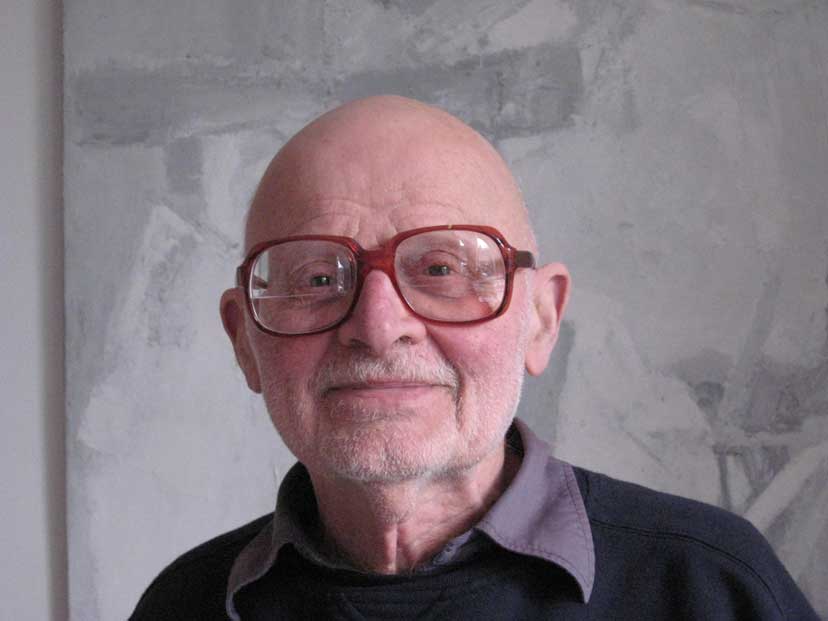

Peter Danby.

Peter Danby.

Unless otherwise specified, all images © Gary Danby

Author: Kate Garrett