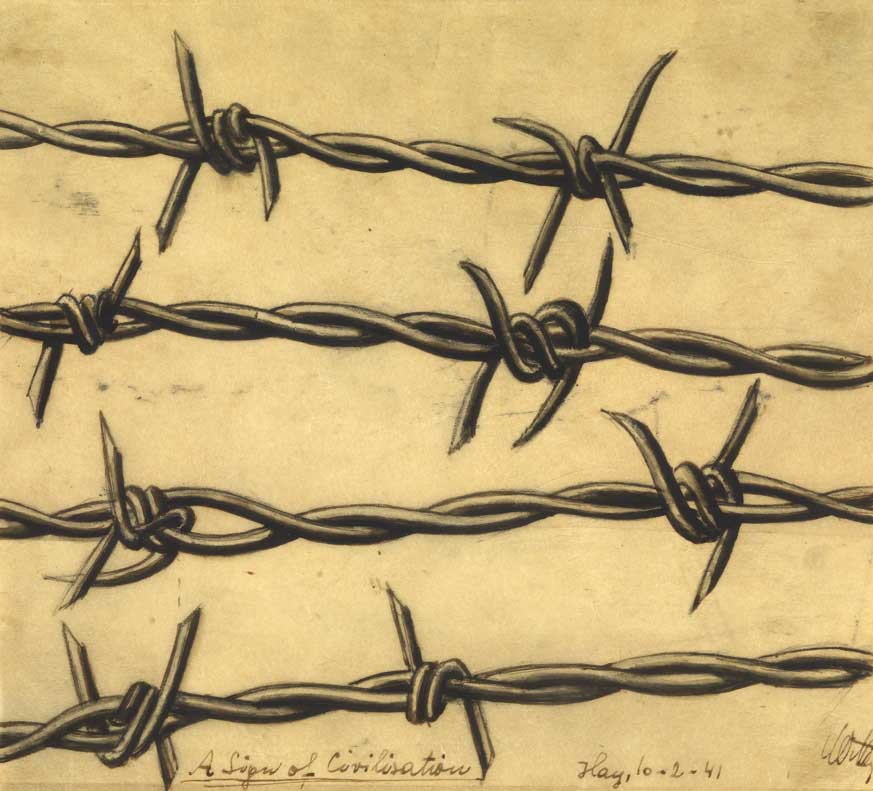

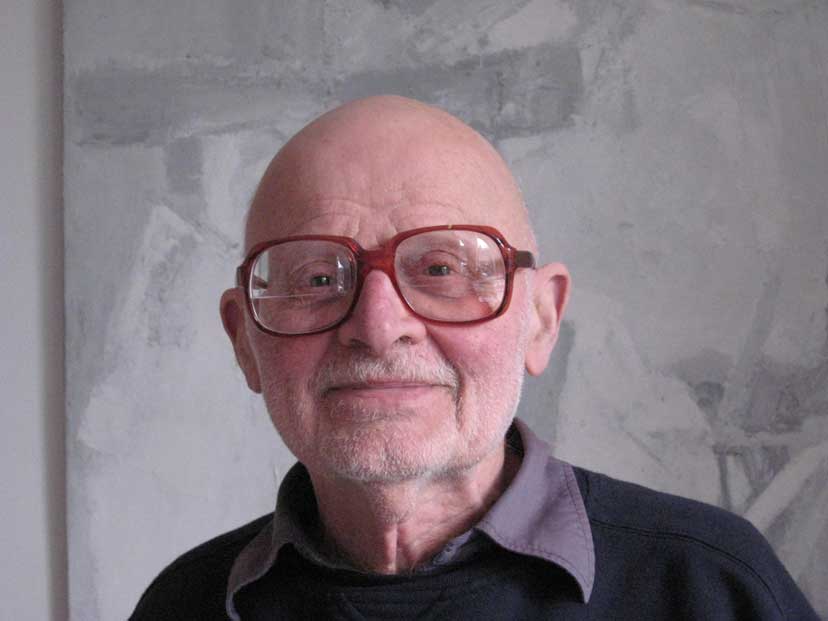

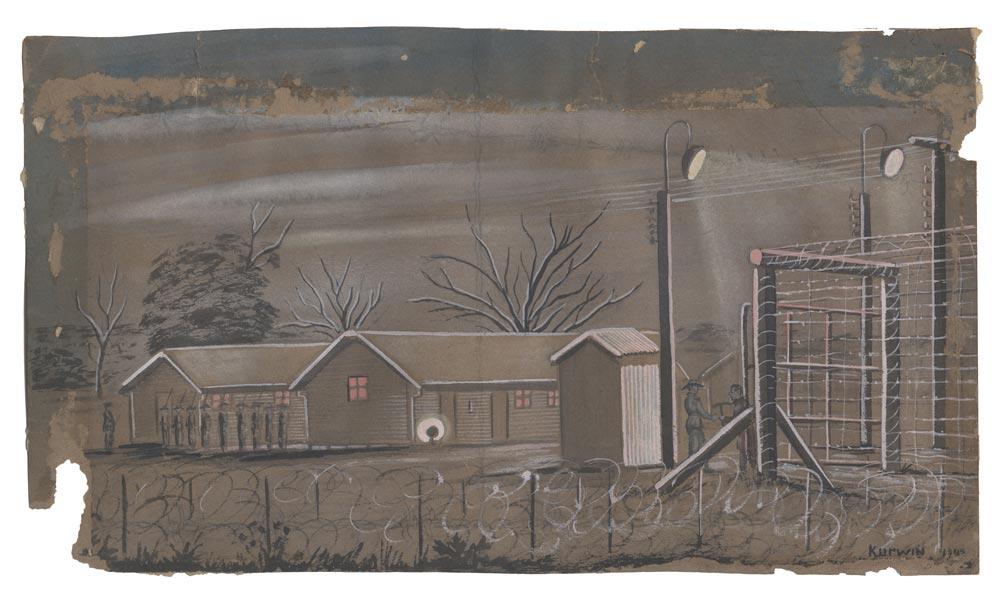

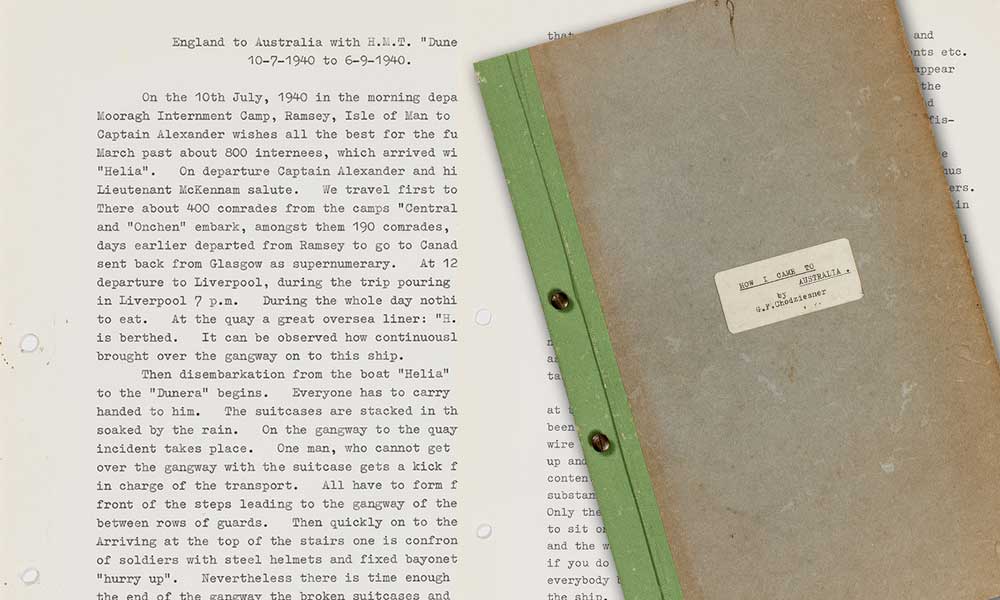

We knew we had our work cut out when we started our search for Emil Wittenberg, one of the most prolific of Dunera artists. We'd seen many of his artworks of course – the image of dreary internees huddled behind thick barbed wire; the hand struggling to free itself from the nails and wire that tacked it to the ground. And we'd heard there may be still a mural he painted located somewhere in Melbourne. But with little else to go on, we organised an interview with his nephew, Martin Burman, and – as we have experienced many times throughout the course of this project – from there the story began to spread.

The iconic Emil Wittenberg hand.

The iconic Emil Wittenberg hand.

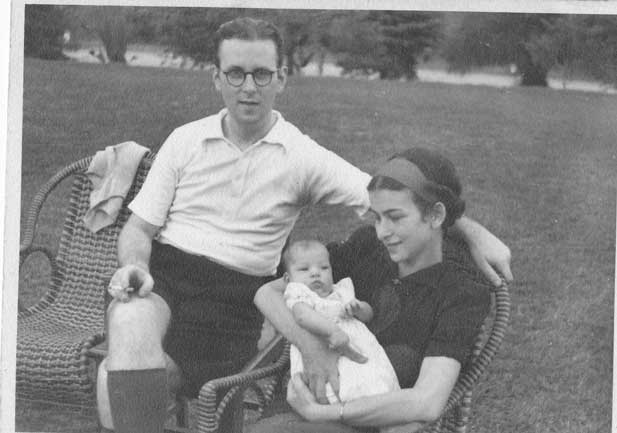

Emil Wittenberg (later Witten) was Martin's uncle by marriage, the husband of his maternal aunt, Gerty. He has many fond memories, he tells us, of his childhood, in which both his uncle and aunt played significant roles. Martin remembers them as incredibly warm and friendly. Martin's parents often ate with Emil and Gerty and they frequently spent time at each other's houses. He asks if we're recording, and when we offer to turn off the tape, he says, no, he wants to make sure this is recorded: ‘[Emil], and my aunt for that matter were absolutely beautiful people, loving and warm… they treated me like their son, both of them’.

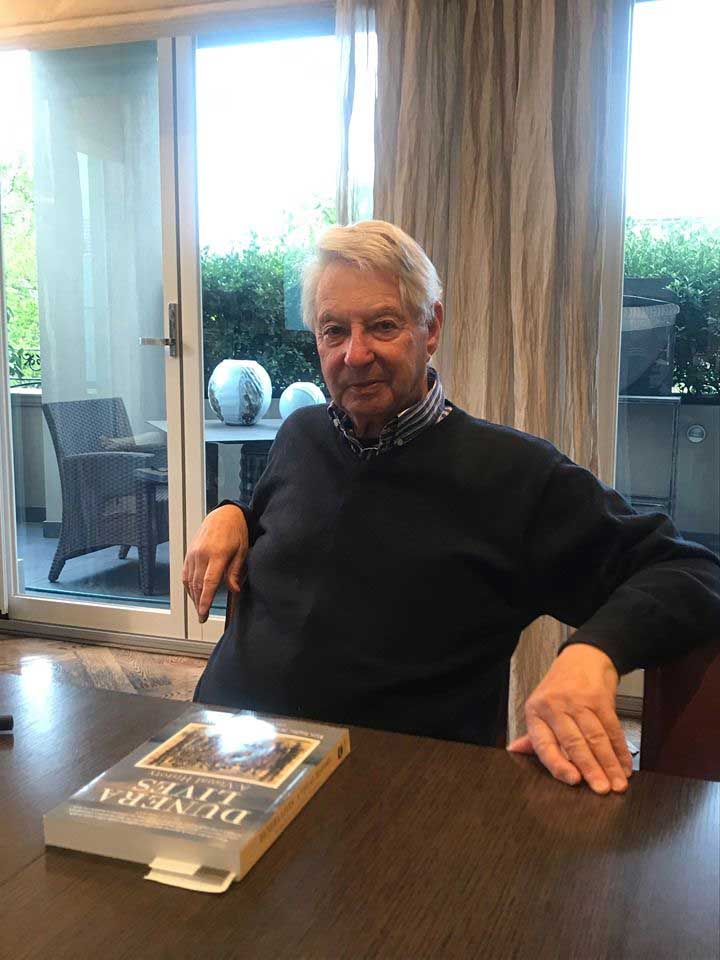

Because Emil and his wife did not have children, Emil's vast collection of work, ranging from sketches made during his time on the Dunera and in internment, to depictions of set designs, is now in Martin’s possession. When we walk in, he tells us he would offer us a seat in the living room, but there's no room: the sofas and coffee table are covered with Emil's notebooks, drawings and framed artworks.

The front side of Emil's proposed design for the Camp 7 currency.

The front side of Emil's proposed design for the Camp 7 currency.

Martin tells us that Emil never spoke about his experiences, and for that reason there are many gaps in his knowledge about Emil's life. There are so many questions he wishes he had asked. While he knows that Emil was born in Vienna in 1910, he isn’t clear, for example, on how Emil met Gerty.

Martin knows very little about Emil's life in Vienna before his escape to Britain – and even how he managed to make it there at all. Martin tells us what he knows of Emil's family in Vienna. Both of Emil’s parents were from Austria. His father, Oskar Wittenberg, was born in Linz, his mother, Regine Fischer, in Vienna. Emil's father died many years before the outbreak of the war, when Emil was just ten years old. His mother remained there until the Nazis were welcomed into Austria. She was murdered in a concentration camp not long after. Emil's sister, Stella, survived the war, and with Emil's help was able to come to Australia. Though she and Emil were not particularly close, he continued to support her in Australia. According to Haywire, published by the Hay Historical Society in 2006, Emil’s path to Britain was convoluted, as was true of many refugees at the time. He fled Vienna via Romania and Cyprus before making it to Britain. Martin speculates that Gerty must have supplied the Hay Historical Society with this information. He never heard it himself.

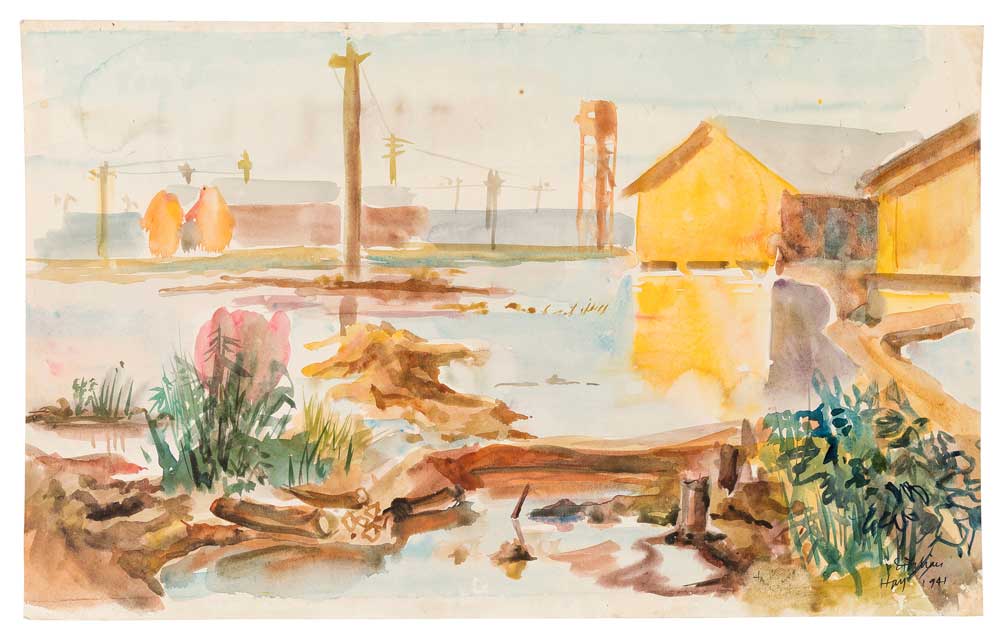

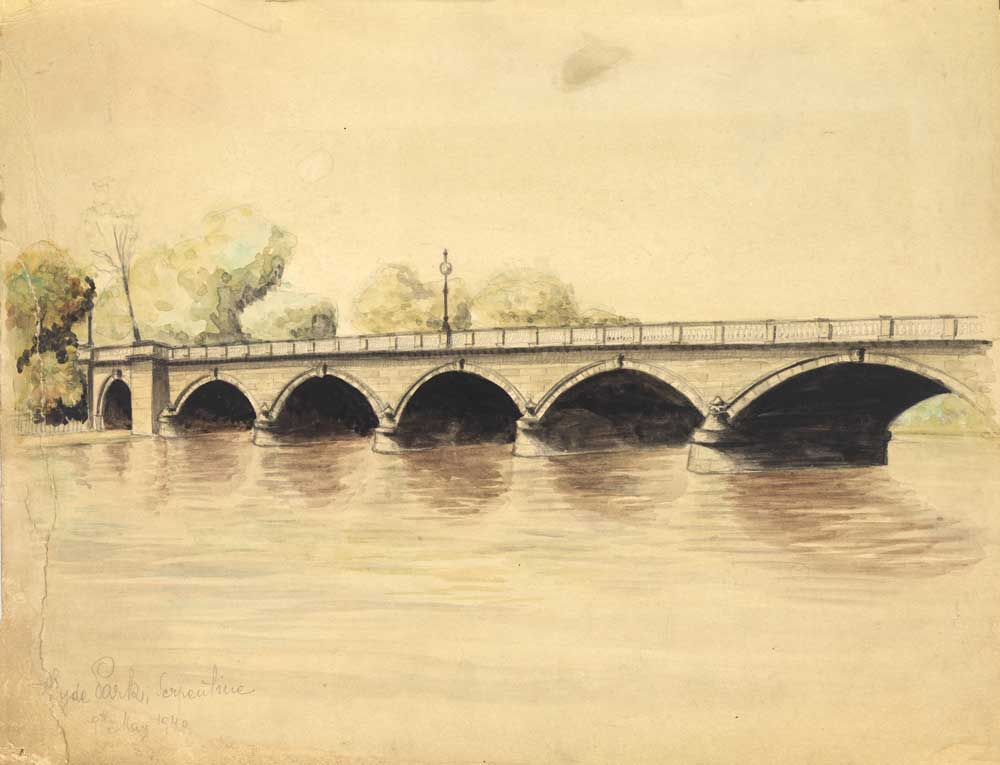

A drawing of Hyde Park, from 1940.

A drawing of Hyde Park, from 1940.

While living in Britain, Emil was employed as a director of furniture manufacturer James Gilbert & Company and, using his sketching skills to his advantage, he became involved with various different theatre companies. On arrival in Melbourne, after he was released from internment, he did the same. He became involved with the University of Melbourne's Union Theatre for a time as a set designer. Emil is also well remembered for his involvement in the 1943 production of Sergeant Snow White, a performance produced and organised by Dunera men in the 8th Employment Company. It was a celebration of the end of the company's first year together and for many it was a de facto celebration of their release from internment. The performance saw Hitler depicted as Europe's 'Big Bad Wolf', with many other satirical references to the war.

Emil made a living manufacturing furniture in a two-story shop on Melbourne's Chapel Street. The furniture was made upstairs, and downstairs was a shop front, displaying his furniture, all sorts of tables, trinkets and other pieces. Not long after he was demobilised from the military in October 1945, Emil and Gerty set up 'Luxury Upholstery', the furniture manufacturing business, and 'Witten's Interiors'. The companies continued to trade from their Chapel Street location for the next twenty years.

The back of the store as it appears today. The door and pulley system at the top of the building still remain. (Image: Kate Garrett)

The back of the store as it appears today. The door and pulley system at the top of the building still remain. (Image: Kate Garrett)

While he made a name for himself in Australia manufacturing and selling furniture, Emil was a man of many talents: he was trained as an architect, and designed his own family home at 4 Theodore Court, Toorak. Though no longer in the family, the house is still there, and while some of it has been renovated, Martin tells us that many of the internal features remain, and that from the outside, it looks almost the way it did when Emil designed it in the late 1950s.

Martin tells us that Emil was never vocal about his experiences on the Dunera. It was only after Emil's death that Martin started to talk more with his aunt about his history. That's how, he tells us, all the drawings came to light. How did Martin first begin to learn his story? Martin says it would have been a few years after Emil's premature death in 1966 at just 56. Martin remembers Gerty mentioning that she had all these drawings – the ones that now fill his living room – and he was curious.

Train tracks extend through broken barbed wire far off into the distance.

Train tracks extend through broken barbed wire far off into the distance.

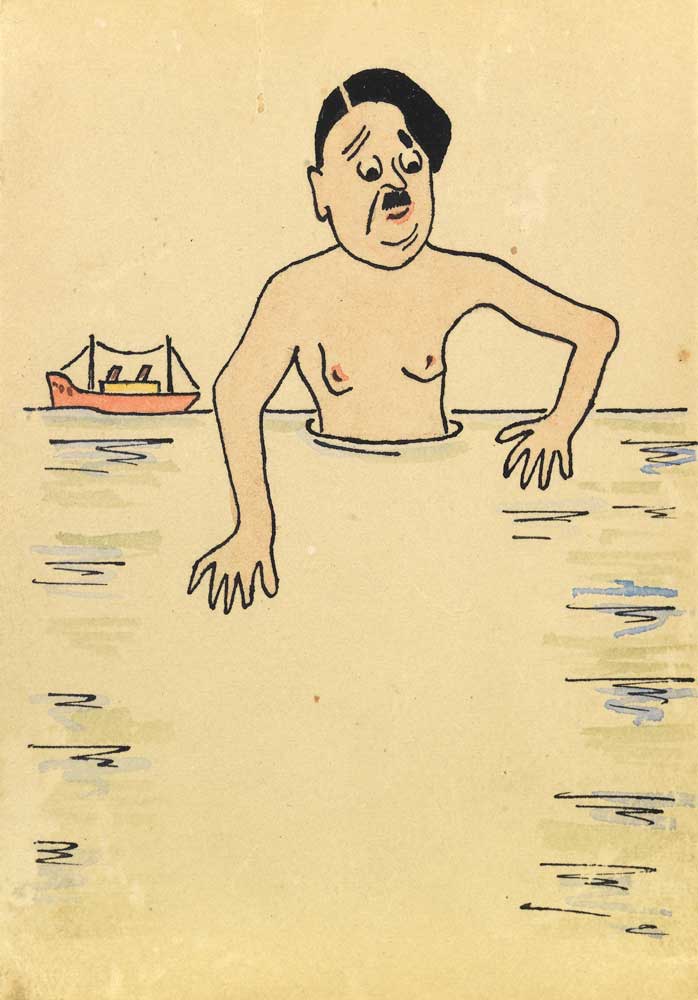

After we finish the formal part of our interview, Martin shows us over to his sitting area, where he has Emil's dozens of artworks spread out across the couches, along with a notebook of sketches, newspaper clippings, photographs and more. The entire notebook was digitised by Hay museum some years ago. The images are beautiful. As we open the folder containing these documents, one of Emil's more recognisable drawings falls out – the one depicting Hitler in the water that shows quite a different scene when back lit. Martin picks it up and tells us he's glad he found this. He moved house recently and had misplaced it among Emil's other work. He walks over to a blown glass lamp, and tucks it just under the lamp shade, where anyone entering the dining and living area would see it. This is always where it went, he tells us.

The drawing of Hitler in the water. The top image is how it appears at first glance. The bottom image is what appears when the paper is held up to light.

The drawing of Hitler in the water. The top image is how it appears at first glance. The bottom image is what appears when the paper is held up to light.

‘Talk to your family now,’ he urges, ‘because when they are gone, they're gone. Ask the questions you want to ask now’, he tells us: ‘there are so many questions I have, so many things I would like to understand now, that I simply cannot get the answers to’. I ask what question he would like to have answered. He doesn’t hesitate: ‘I would like to know why my parents, aunt and grandparents left Austria when they did. What one thing made them decide they needed to leave? Or was it more than one thing?’

Martin reveals that it was more than just his maternal uncle who was affected by Hitler's brutality. One of Martin’s mother’s cousins, a ship worker, sailed to Darwin, jumped ship and became established in Australia at the beginning of the 20th century. Naturalised before the start of the Second World War, he was able to sponsor Martin's mother's family to come to Australia. Martin's father's story was less straightforward. His father and uncle escaped to southern Italy and through their connections were able to obtain visas to Australia and also to the US – where some of his extended family still lives.

Something Martin returns to throughout the interview is the sheer challenge of trying to understand what lay beneath these stories. He points to the individuals huddling behind the barbed wire – a drawing that for many has become synonymous with the Dunera experience. Each of them, he says, is an individual, and should be remembered that way. On thinking about the many millions of Jews murdered during the Holocaust, and others who survived the war but with family forever torn apart, he avoids counting numbers: it’s easy to forget that every single person that lived, died and suffered through that time was an individual. ‘It's really, really sad because every one of the people here that we're talking about … all of these people – and there are millions of them – they have things they like, things they don't like. They have personalities. They contributed to society in thousands of ways and they were all individuals. It's not just a group or a number.’

Unless otherwise specified, all images © Martin Burman

Author: Kate Garrett