In May, 2019, two of our team travelled to Canberra to interview Bern Brent – in his words, ‘one of the last Dunera boys still vertical’. He was with two of his adult children. We talked with him about his – and their – memories of Dunera, and what it was like establishing a life in Australia in the 1940s. The following is a summary of our two-hour conversation. You can listen to the full recording here.

Interview with Bern Brent

On first meeting Bern Brent, you'd be hard-pressed to guess his age. He's tall, slender, with deep-set eyes, and a full head of hair. It's clear Bern has been interviewed many times: he's animated when he speaks, makes eye contact, and recounts with remarkable ease details from decades earlier. The only thing that gives away his 96 years is that we have to sit near him and raise our voices slightly when we speak.

We're sitting around the living room table in his Canberra home, where he's lived for the last forty years – since his return from training teachers of English for close to a decade at Saigon University and Gaya College in Sabah, Malaysia. Walking to the front door, we wonder whether we've picked the wrong house. The front yard is a tangle of native trees and shrubs, with a gum tree stretching its branches above . A hard to find path leads us to the front door, where we're greeted by an excitable dog, as well as Bern and his children, Joanna and Peter.

Bern Brent was born Gerd Bernstein, a name he has not used in decades – not since he farewelled Germany in 1938. Though he could not have known at the time, as with many of his contemporaries, that was the last time Bern would live in Europe. He did return to visit many years later, but never ended up spending more than a few days at his childhood haunts. He tells us he is planning another trip – final trip, he says – to Berlin, where he hopes to spend more time than in past visits.

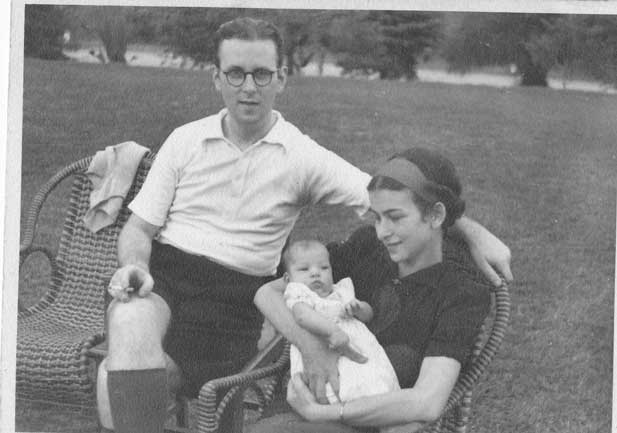

Bern Brent, c. 1942-45.

Bern Brent, c. 1942-45.

Born in 1922 to Otto Bernstein and his wife, Moscow-born Helene Maas, Bern spent the first fifteen years of his life in Berlin, a city of which he has many fond memories. Berlin, he tells us, was ‘not like Vienna and perhaps some other smaller towns’, where a culture of anti-Semitism was deeply entrenched. Even at that time, it was a cosmopolitan city, and Bern says he experienced it as that: he was not subjected to the humiliation and persecution that others in smaller towns or cities remember. One of his main memories is of a kindly neighbour – the wife of a man in the feared SA – welcoming him into her home when she found him cold and crying at the front steps of the apartment after realising he'd forgotten his key on returning from ice skating.

The older he gets, Bern tells us, the more the memories of his childhood come back to him. He finds himself humming ditties that were popular when he was still in school. He's written a memoir of this time in his life, which is peppered with an astonishing number of snapshot memories and minute details.

Bern's parents divorced when he was still relatively young, a fact he says he did not fully grasp for a number of years. In spite of the divorce, his parents remained close, eating together several times a week and continuing to make joint decisions about young Bern. It was his parents who, believing in 1937 that a war was likely, decided that he should leave Germany. His connection to the Quaker community meant Bern was able to get a spot on one of the first Kindertransports; he left for Britain at the end of 1938.

Bern was one of the men who volunteered to board the Dunera, doing so at the suggestion of his friend Peter Danziger. Bern was one of approximately 30 per cent of internees who was not of Jewish faith. In Huyton internment camp, where Bern had been held before the Dunera sailed, they were told everyone was going to be sent to the Dominions, possibly Canada. Though Bern acknowledges that to call the trip pleasant would be misleading, he denies the sensationalised stories. Lieutenant Colonel Scott, the officer who commanded the guards, was without a doubt a ‘bastard’, but Bern has no memories akin to the sensationalised stories of maltreatment that would become the fodder for the 1985 television mini-series.

Bern Brent (centre) and friends, c. 1942-45.

Bern Brent (centre) and friends, c. 1942-45.

We talk at length about why he believes the story of maltreatment and suffering gained such traction. Part of it, he speculates, is that bad news sells – and even if these views represented a minority, their voices were, understandably, the loudest. He does, however, admit that as a teenager he had had it easier than people in their forties or fifties. Did his circumstances mean he was less aware of maltreatment? He was not leaving behind a wife or children in Europe, there was no career being put on hold.

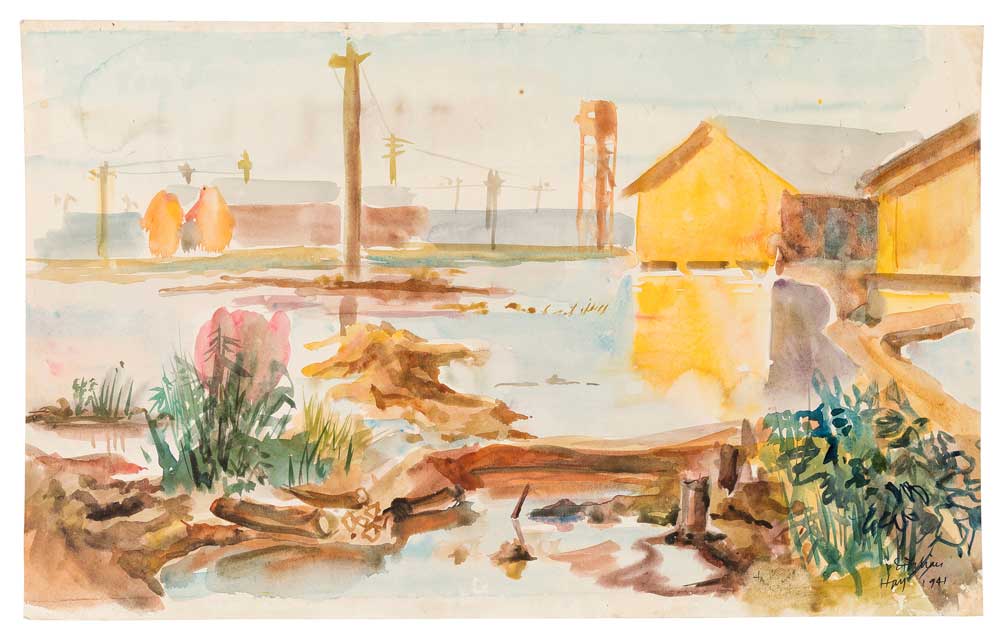

Unlike most of the non-fascist internees aboard the Dunera, Bern was sent directly to Tatura, along with about another hundred internees, as well as the German and Italian survivors of the Arandora Star, many of them Nazi sympathisers. The fascists were soon separated from the rest, and Bern focussed his efforts on pursuing his education. He was interned in Tatura for nearly eighteen months. In early 1942, he was released to pick fruit in the Goulburn Valley, on his way to joining the Australian army.

Bern Brent (right), c. 1942-45.

Bern Brent (right), c. 1942-45.

Initially, Bern intended to return to Europe. His name was on the list of returnees, but as a young, single male, his passage to Europe was not a priority, and when his turn finally came in 1941, the Pearl Harbor attacks meant the ship that was to take him to Britain was diverted to Singapore to carry munitions. Bern decided to remain in Australia for the duration of the war. Though not his choice, he came to see it as a wise decision. ‘What was I going to do in Britain after the war?’ he writes in his Thirty Years. ‘I had lost contact with almost everybody … In Australia I had friends.’

Bern's parents joined him in Australia. First, his father, who having survived three years in Theresienstadt was one of a minority of prisoners to see liberation in 1945. Bern's grandmother and aunt were less fortunate; they were murdered in Theresienstadt. Bern's mother and her friend, Gaby, who would become a lifelong friend, were next to come to Australia. Both had managed to escape Germany just before the war, acting on the advice of a telegram from Bern. His mother’s friends had been sceptical, arguing that Bern was only a child, and she didn't need to follow his advice automatically. But his mother heeded the warning and she and Gaby left for London that very night on what turned out to be the final boat train before Germany sealed its borders and invaded Poland. As Bern recalls in his memoir My Berlin Suitcase, he never doubted he would see his parents again.

It was the warmth with which Australia welcomed Bern that, in many ways, had the biggest impact on his decision to stay. An interned dancing teacher gave lessons on ballroom dancing, and this came in useful when he was on army leave; he and many of the other young soldiers would go to St Kilda in bayside Melbourne to dance. Through dancing he connected with young Australian women, who occasionally introduced him to their families, who in turn welcomed him into their homes. He remembers with particular fondness one family who went so far as to organise a bicycle for him to be able to ride around the city with their daughter.

Bern was introduced to his future wife, Jean Lloyd Siddins, by a former colleague, who happened to visit from Italy and invited both aboard his docked ship for a drink. Bern and Jean were married in 1958, and a month after the wedding, they left Australia for Saigon. Bern had, under the Colombo Plan, applied successfully for the role of Lecturer in Methods of Teaching English as a Foreign Language at Saigon University. Bern's expertise had started much earlier: after completing university after the war, he had taught English to migrants; been chief instructor, research officer and district supervisor of adult English classes with the Snowy Mountains Authority; and shipboard education officer as well as advisor to the International Committee for European Migration in Geneva.

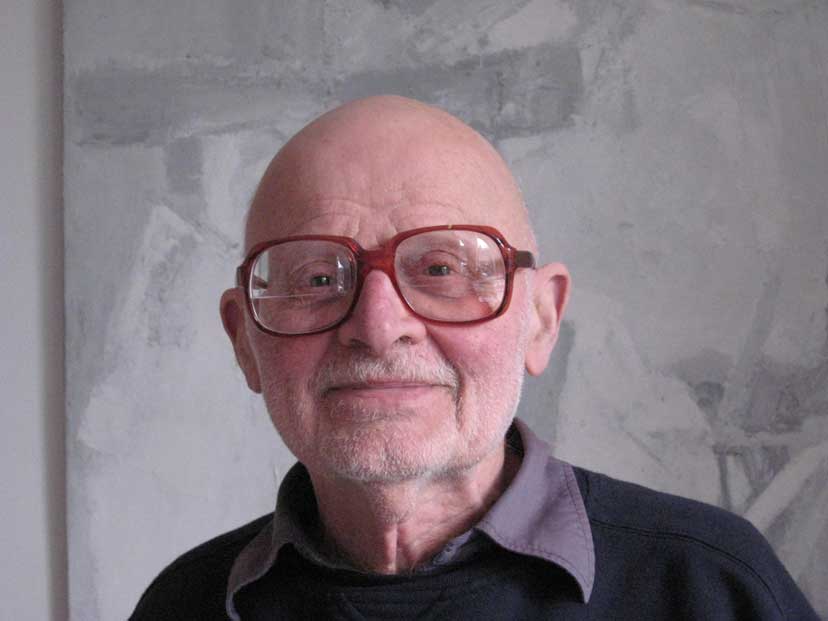

Bern Brent, c. 1942-45.

Bern Brent, c. 1942-45.

Bern and Jean would not return to live permanently in Australia for almost a decade: Bern's initial Colombo Plan assignment received two extensions, and in 1963 he began a new job as head of the English department at a teacher's college in Kota Kinabalu (formerly Jesselton), Borneo. Bern and Jean's first child, Barbara, was born in June 1959. They went on to have two more children, Peter and Joanna. In 1968 the family returned to Australia, first to Sydney, then to Canberra in January 1969, where they settled.

Reading My Berlin Suitcase, I'm struck by the sheer number of Australianisms Bern uses: from ‘mate’ to ‘bathers’, a distinctly regional word that gives away the seaside location where he became immersed in Australian culture. I remind myself that Bern has spent decades of his life in Australia - indeed the vast majority of it, and we discuss his sense of belonging. It's interesting too, as Peter and Jo join the discussion, to hear their perspectives: though Bern arrived in Australia as a teenager, to them, he was always very much their German father, an outsider to Australian culture. He encouraged his children, especially Jo, his youngest, to study German, but Bern says he never put pressure on them to learn the language or embrace their German background.

From the outside, you'd be forgiven for thinking Bern's life was one marked by struggle or sadness. But Bern's optimism and warmth are infectious. As we begin to wrap up the interview, he wants to make it clear how lucky he feels to have had the opportunity to come to Australia and build his life here. Bern leaves us with one final thought, best put in his own words:

‘I do want to say for the record, that to me, the best thing that could have happened to me in England in 1940 was to get interned and be sent to Australia. Had I stayed in Britain, I don't know what could have happened to me, I don't know how my life would have been. I don't know whether I would have survived the war because they would have put me into the infantry... There's no question that I'm pretty sure I had a better life in Australia than I would have had in Britain. So, I'm very happy to have been sent here.’

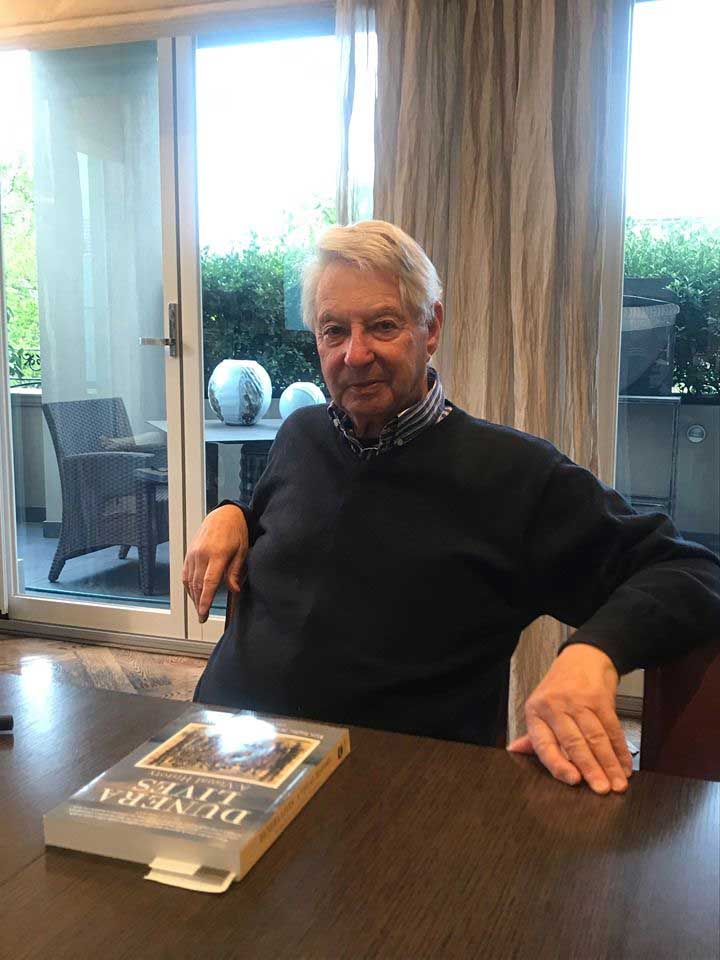

Bern Brent, 2012. (Image: Anna Wolf)

Bern Brent, 2012. (Image: Anna Wolf)

Unless otherwise specified, all images © Bern Brent

Author: Kate Garrett