Miriam Gould tells the story of her parents, Werner and Ilse Baer.

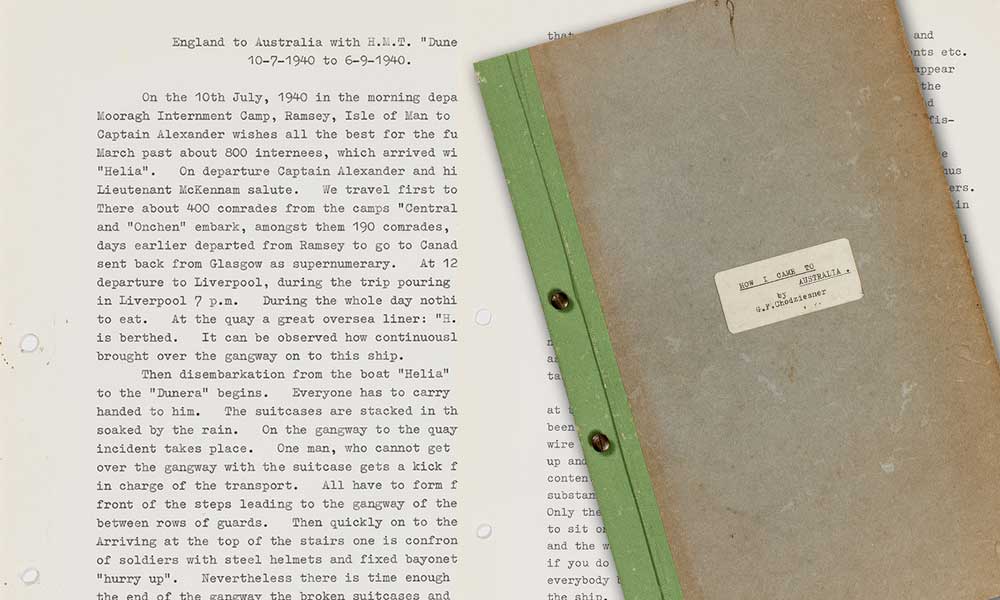

Remembered today as a composer and broadcaster in Australia’s mid-twentieth century music scene, Werner Baer’s earlier history was marked by imprisonment and internment. Baer escaped Berlin with his wife Ilse in 1938, only to be interned with their newborn Miriam in Singapore and put on board the Queen Mary in 1940— a British luxury liner converted to a troop ship during the war, and in 1940, given the same task as the HMT Dunera: deliver internees to Australia. The story of Baer and his family forms part of the rich tapestry of internment in Tatura, Victoria.

We are at Miriam’s dining table, looking over photo albums, old documents and portraits that reveal the extraordinary journey her family embarked upon in the late 1930s. It all began in Berlin.

Werner Baer was no ordinary student. ‘Music, as he would have told you’, Miriam says, ‘from every age of his life was his life.’ He started learning piano at the age of three, and as a student was taken out of ordinary schooling to study music and performance. His mother would leave a sweet on the piano, but he needed no incentive to practise. Within the music scene of the Weimar Republic, Baer learnt classical music yet experimented also with other genres: he played organ at several Berlin synagogues and, outside of classes, dabbled with jazz.

An old document of Werner's. It reads: "My signature confirms that I am a Jew in the sense of the Reich laws, that I accept the conditions of the Reich Association for my membership and that these conditions may be revoked if necessary".

An old document of Werner's. It reads: "My signature confirms that I am a Jew in the sense of the Reich laws, that I accept the conditions of the Reich Association for my membership and that these conditions may be revoked if necessary".

Werner found love with Ilse Presch, a young woman who wished to be a journalist. On hearing her aspirations, Ilse’s father told her he could not support her training; she needed to find a vocation that transferred well to another country, in case she had to leave. He found her a position as an apprentice dressmaker. Decades later in post-war Australia, Ilse reflected gratefully on the decision her father had made. Yet at the time, she resented the direction her life was taking. ‘She was horrified’, Miriam recalls. ‘She had to go and clean up and sew and be yelled at. This was a very cosseted middle-class girl.’

Ilse and Werner were married in May 1938, a young couple in their early twenties. Berlin was becoming an increasingly dangerous place. After the terror of Kristallnacht in November 1938, Werner Baer and his brother Fritz were interned in Sachsenhausen. Guards confiscated the possessions of inmates, shaved their heads and subjected them to awful indignities.

In 1938, the Nazi regime allowed concentration camp inmates to leave if they could provide proof that they would leave the country immediately. Ilse bravely approached the Nazi guards at Sachsenhausen in December 1938 and asked for Werner’s release, producing two tickets she had been able to purchase for the Potsdam, bound for Shanghai

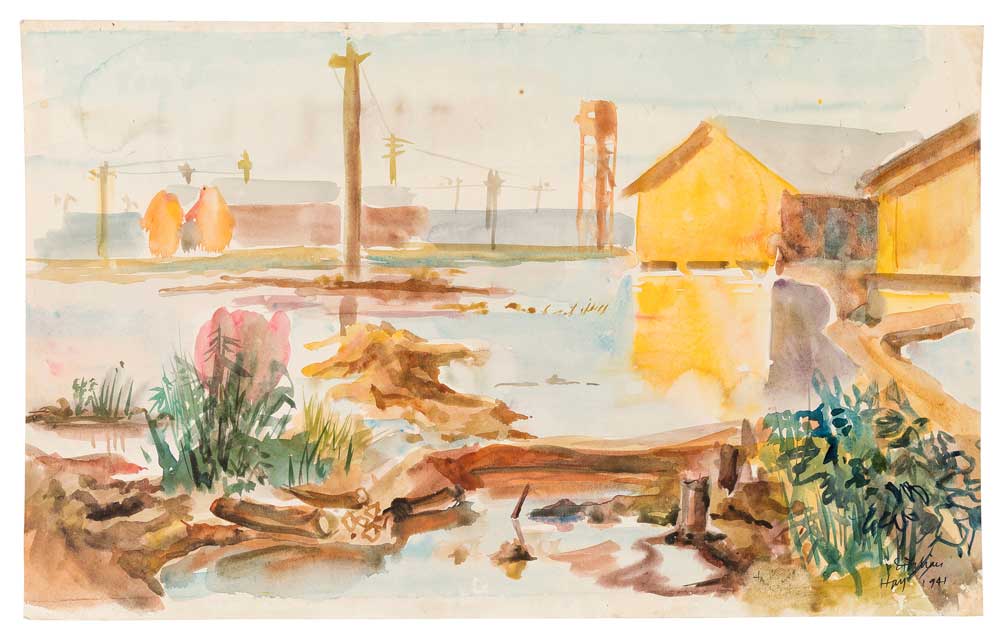

Werner Baer shortly after his release from Sachsenhausen, 1938.

Werner Baer shortly after his release from Sachsenhausen, 1938.

The Baers on board the Potsdam, on the way to South-east Asia in December 1938.

The Baers on board the Potsdam, on the way to South-east Asia in December 1938.

On the ship to Shanghai, the Baers heard of a position in Singapore for an organist and music teacher. They decided to take the opportunity and settle there instead. This was not an unusual path to take; other Jewish refugees headed for Shanghai opted for Singapore, including Karl Duldig and his family. A British dominion, Singapore offered a thriving expatriate community and considerable job opportunities.

Soon after arrival in Singapore, the Baers managed to make provisions for some of their family members. Werner was instrumental in helping his mother, and brother Fritz, reach Shanghai by way of Siberia; they stayed in Shanghai for the duration of the war before joining him later in Sydney. Ilse’s brother, Heinz, had managed to emigrate to Sao Paulo in 1936. In 1939, Ilse sent him a telegram urging him to get their parents out of Germany. Heinz showed the telegram to the Brazilian authorities in Sao Paolo, who then supplied visas to his parents. They sailed for Sao Paulo later that year, in 1939.

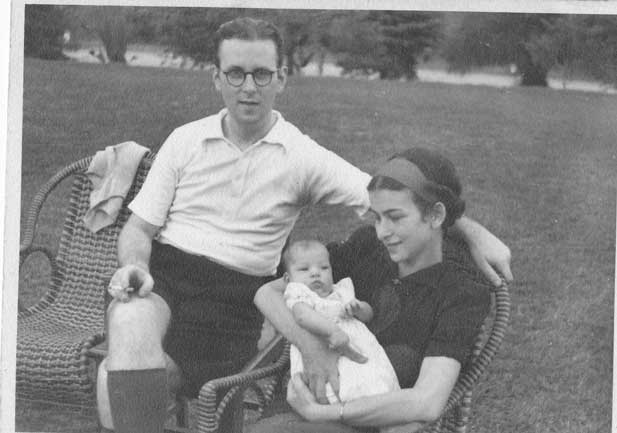

The short time that Werner and Ilse spent in Singapore—under two years—was idyllic. Werner enjoyed the music scene while Ilse worked in a clothes salon. In October 1939, the couple welcomed their first, and only, child Miriam. Their new, fast-paced life changed forever when, in September 1940, British authorities ordered them to appear at the wharf the following day, bringing only that which they could carry. Their hearts sank; such a message hinted at deportation.

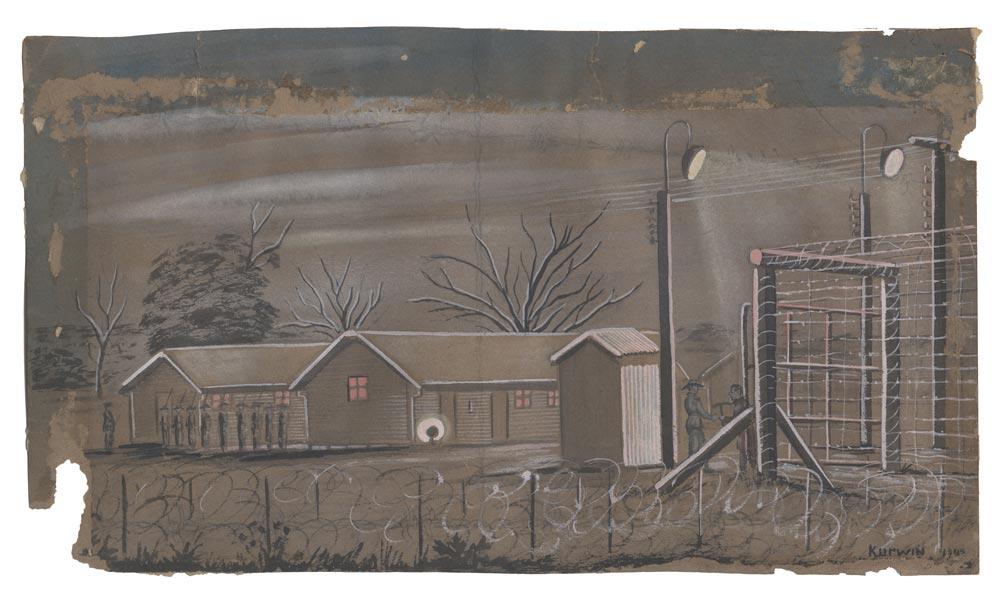

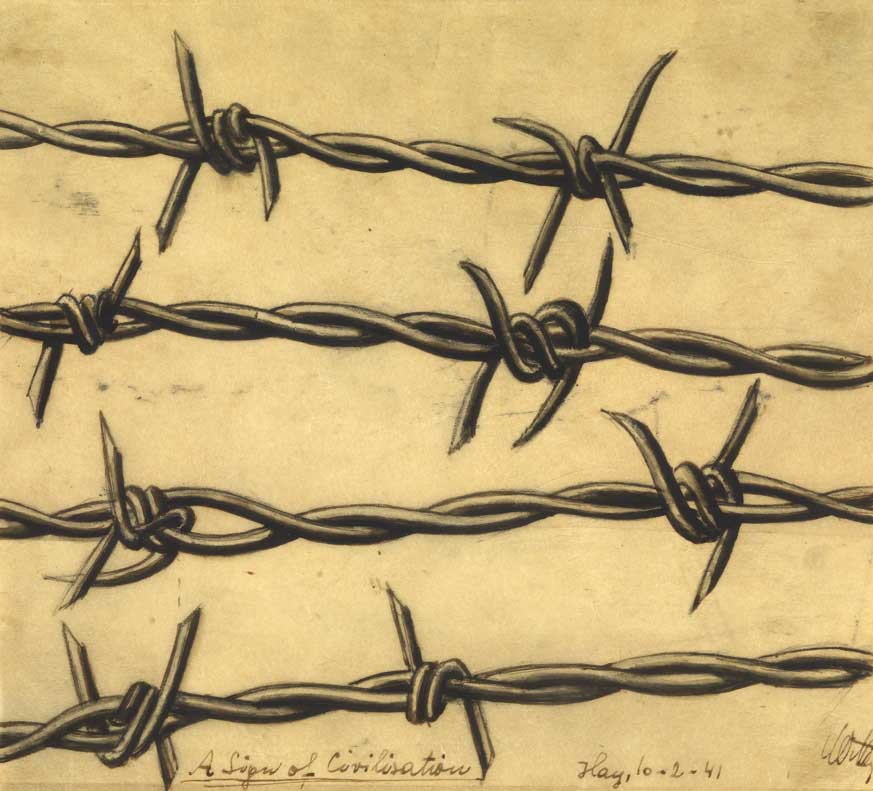

The Baer family found themselves headed for Australia aboard the Queen Mary. The passage over was a comfortable experience, with three course meals and nice rooms. To the European eye, the desolate landscape and barbed wire of the internment camp where they ended up—in Tatura—provided a bleak contrast.

Life in Tatura, much like the journey on the Queen Mary, was one of many contradictions. The young family found themselves confined in a camp in a foreign land, yet they were safe from the terror that had consumed Europe and was spreading to Shanghai and Singapore. ‘It was a camp, it was regimented, the soldiers were fantastic, it was hot… corrugated iron roofs, you know. But it was safe.’ So says Miriam, recalling her parents’ memories. ‘I don’t think it was an unhappy time, but it was a disruptive time.’

The Baer family in front of their hut in Camp 3, Tatura, 1940/41.

The Baer family in front of their hut in Camp 3, Tatura, 1940/41.

Invitation to an evening of entertainment in the camp.

Invitation to an evening of entertainment in the camp.

And an anxious time. Someone in Camp 3 had a radio, and the internees would listen intently to Churchill’s speeches. Ilse later would speak of the tense uncertainty, of not knowing whether Hitler would win. There was also uncertainty regarding loved ones. Correspondence between Ilse and her mother was delayed and censored, and it was only in Tatura that Ilse heard of her mother’s death months earlier. Ilse spiralled into grief after that.

The internees did the best they could with life in the camp. A kindergarten was set up, and toys and furniture crafted for the children. Ilse felt the loneliness more keenly than Werner, who had male friends with whom he played cards and socialised. The couple were young, vibrant and headstrong; they had been married only five months when Hitler turned their lives upside down. Werner composed music for various recitals held at Tatura. Hans Blau, an internee who wrote the words for many of Werner’s songs, would later become Ilse’s second husband.

Werner, in uniform, with Miriam, 1944.

Werner, in uniform, with Miriam, 1944.

After more than a year in Tatura, Werner took the opportunity to join the 8th Employment Company—a labour unit of the Australian army. The unit’s commander was Captain Edward Broughton, a humane leader loved by his men. He noted Werner’s talents and put him on latrine duty. While by no means a pleasant job, this duty would be easier on Werner’s pianist hands and allow him more time in the afternoons to practise his music. Broughton’s kindness helped Werner to win a national patriotic song competition in 1946 under the pseudonym of John Werner. During the war years, Ilse was permitted to live in St Kilda with Miriam on the condition that she reported to the police every week for the duration of the war.

Werner and Ilse had married young, and had drifted out of love while interned. Once discharged from the army, Werner moved to Sydney where he worked as choir master and organist at the Great Synagogue. He would remain in Sydney for the rest of his life. Ilse remained in Melbourne with Miriam. The couple’s divorce took eight years to be processed, and by that time Werner had met his second wife, an Italian-born woman named Sybil.

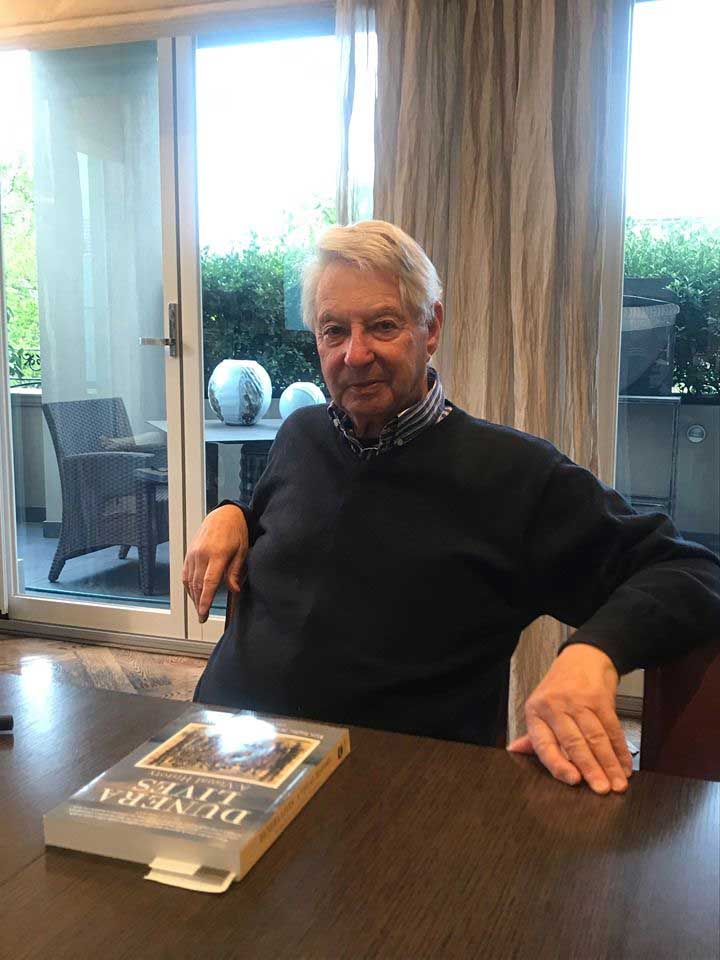

Werner went on to play piano for the Australian Amateur Hour, a popular program that aired each Sunday on the ABC. He then worked for the ABC as an administrator, and at different Sydney synagogues. He adjudicated local and national music competitions, and helped develop the technique and accent of singers at the Australian Opera. Werner remained a musician of the old European school, never warming to modern music. In 1977 he was awarded an MBE for his services to Australian music.

Werner later in life.

Werner later in life.

What did Werner and Ilse make of their new lives in post-war Australia? Miriam speaks of their sense of gratitude and luck in this new country. ‘Werner was proud of his European heritage, identifying as more European than German. Yet at the same time he felt very much an Australian; he loved Australia and was incredibly grateful.’ He disliked dwelling on the horrors of the concentration camp, focussing instead on his happy childhood in Berlin and the wonderful concerts he attended when he returned to Germany on post-war trips. He called himself an ‘honorary’ Dunera boy, identifying with the experiences of those men while acknowledging his own journey with the Queen Mary group had differences. Through his love of music, he led a dynamic and passionate life until his death in 1992.

Ilse was delighted to enrol in university courses later in life, and trained for the Citizens Advice Bureau. Through this work she was able to pass on her experiences to others who faced challenges. Speaking at the age of 101, Ilse says she feels blessed to have ended up in Australia all those years ago.

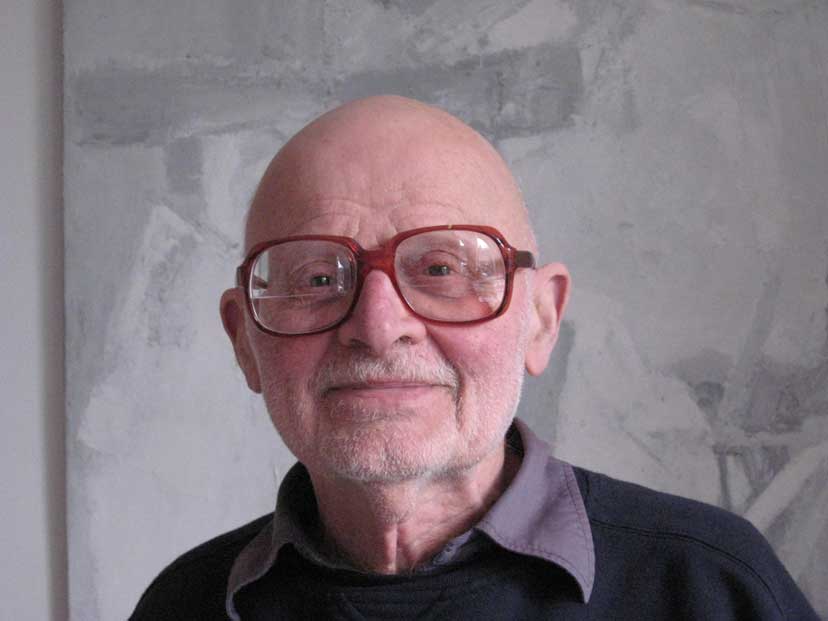

Werner in the post-war years.

Werner in the post-war years.

In memory of her father, Miriam has faced her own feelings regarding the past. In 2018, the Sachsenhausen Museum approached Miriam regarding a special exhibition on the Kristallnacht prisoners of 1938, of whom her father was one. The exhibition, inaugurated at the House of Representatives in Berlin, was named ‘In the country of numbers, where men have no names’. Miriam was ‘beset by contradictory feelings.’ Should the Germans be honouring this small group of men, some, like her father, who had managed to escape when so many had been left behind, tortured and murdered? In the end, Miriam reasoned that ‘the exhibition would highlight the terror that the original incarceration represented, and the triumph of the human spirit that had enabled the men to continue their lives despite never forgetting what they had gone through.’ She feels her father would have appreciated the exhibition.

Ilse with Miriam on her wedding day in 1961. Miriam wore a dress made by her mother.

Ilse with Miriam on her wedding day in 1961. Miriam wore a dress made by her mother.

Ilse and Miriam together in March, 2018.

Ilse and Miriam together in March, 2018.

While Werner is remembered as a notable name in Australian music history, Miriam hopes the incredible story of her mother also will live on. ‘The men did go on to do wonderful things many of them… but they were supported in so many cases by women. Women who must have had their own traumas to go through. My mother was a dressmaker and she had to establish herself. She was a refugee.’ Ilse worked as a dressmaker for the rest of her life. Her English was very good, but she spoke it with an accent and had to combat anti-Semitic prejudice.

Miriam has put together books of photos and documents about her parents’ life stories. They are for her children and grandchildren, Ilse’s great grandchildren. ‘I particularly wanted them to look at my mother…not just as an old woman, an old, vague, witch-like woman, but as a heroine. I wanted [her grandchildren] to read what she’d done, in going to the camp, in getting the visas, in getting her parents out of Germany. I wanted them to see her as something really special.’.

The interview on which this piece is based was conducted in March 2019. Ilse and Miriam live in Melbourne.

All images © Miriam Gould

Author: Georgina Rychner