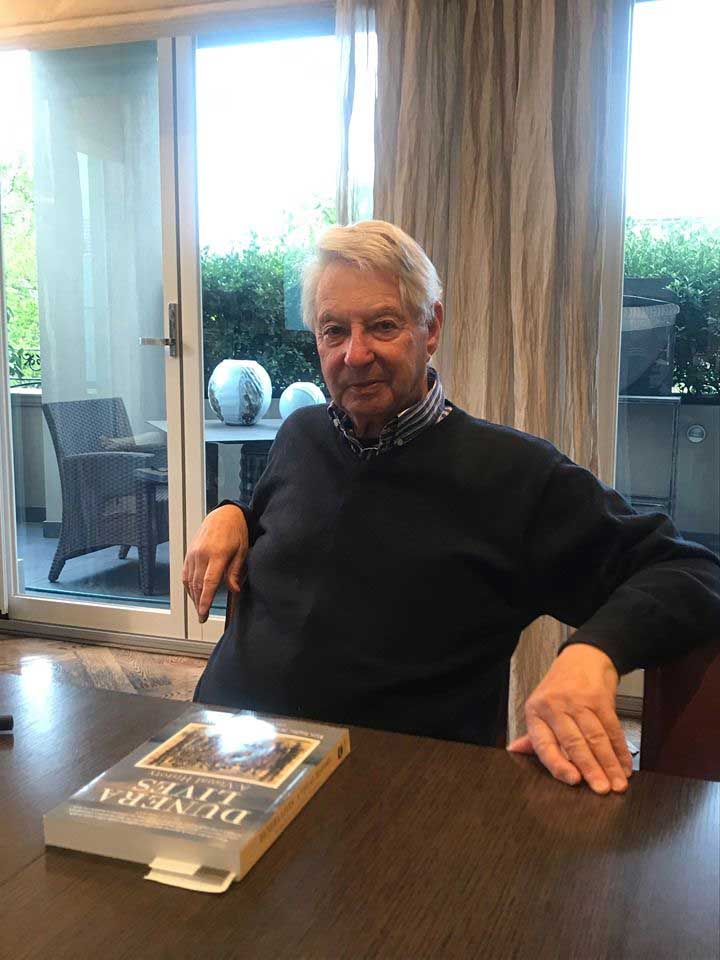

We're greeted at the door of his apartment by Phillip Benjamin himself, a softly-spoken, exceedingly articulate and curious white-haired man in his 80s. As he leads us through his apartment, full of art, books and exquisite furniture, he asks about us and how we became involved with the project. Though several years younger than even the youngest of the Dunera boys, Phillip tells us that over the years he was occasionally mistaken for being one. An accountant and businessman, Benjamin’s early years were dotted with encounters with ex-internees in Melbourne, some of which grew into lifelong friendships. ‘I didn’t really know that many of the people that I had met or had connections with were Dunera boys’, Phillip begins. ‘It only really emerged later.’

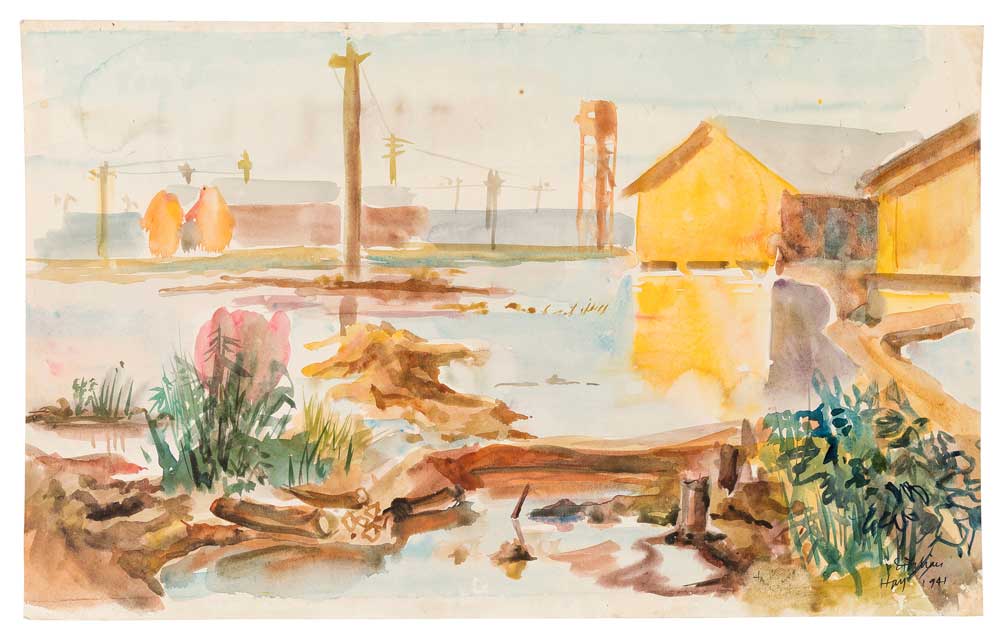

The first chance encounters occurred when Phillip was just a boy living in Elwood. Phillip was ten years of age when his father died, leaving his mother to carry on their printing business. Phillip was placed as a boarder at Mentone Grammar School. His art teacher happened to be Karl Duldig, who also coached him in tennis for several years. Duldig was an Austrian-born sculptor who, with painter spouse Slawa and their daughter Eva, left Austria in 1938 for Switzerland before proceeding to Singapore. In 1940 the family was deported from Singapore to Tatura, Victoria, and after release and naturalisation in 1946, Karl came to be in the same room as Phillip. Later in life Phillip would reconnect and remain friends with Eva and her husband Henri.

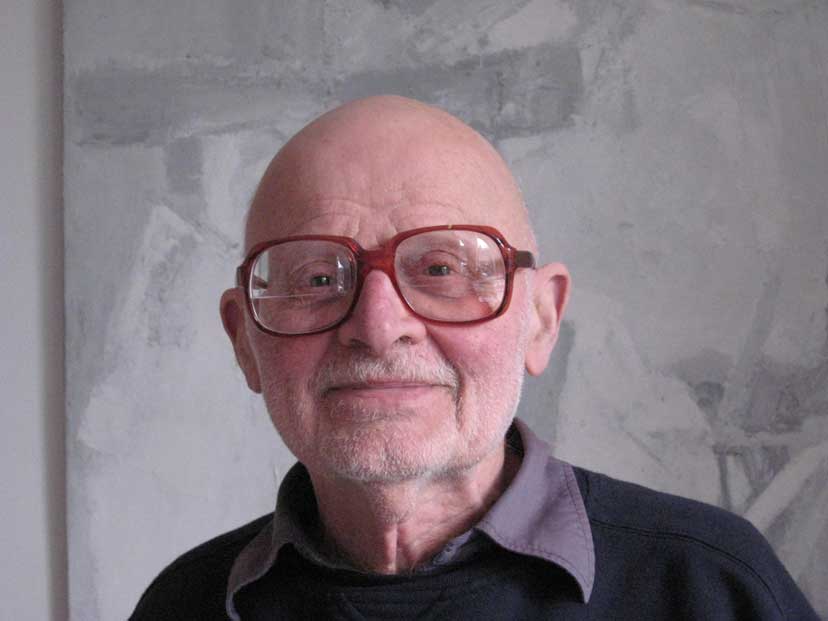

Meanwhile, Phillip’s mother, looking for support in the business, employed a young German commercial artist who had come to Australia. His name was Heinz Tichauer, later to be known as Henry Talbot. Shortly after, in 1948, Henry left for Bolivia to find his parents. On his return to Australia in 1950, he devoted himself to photography, going into partnership with Helmut Newton and forging an impressive career. Henry was perhaps best known for fashion photography.

After graduating from high school in 1950, Phillip began national service with the Australian navy. In 1957 at age twenty-two, and with national service behind him and by this time a chartered accountant, he took his first overseas trip by boat to Europe. The next year he worked at the Australian consulate in New York, handling Australian payment for military equipment. He tells us about his trip back to Australia – buying a one-way plane ticket that allowed him to make as many stops as he wanted as long as he was heading in more or less the same direction. Over the course of many weeks, he slowly made his way back home, via England, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, India, Thailand and Singapore.

By the time he returned, Phillip’s mother had moved to Brisbane for her health, and he initially worked and lived in Brisbane before, at age twenty-six, moving back to Melbourne.

Phillip first stayed with a cousin, whose husband was part of a small syndicate of investors and developers. They occupied an office on La Trobe Street, and he accepted the offer to go into practice as the group’s professional accountant. The informal manager of this syndicate happened to be a Dunera boy: Erwin Frankl.

Phillip's second client was an architect who worked in the same building, none other than Walter Pollock from Vienna. Pollock went on to establish a private practice and gained notoriety in the world of architecture for his modernist glass-walled buildings, in particular his family homes located in Heidelberg and Toorak.

In March 1960, Phillip got to know another chartered accountant, Herbert Baer, who left for Europe not long after. When Baer returned, the two went into practice together. A week into the partnership, Baer handed the client base to Phillip and left for the Melbourne Stock Exchange, the first Jewish man to gain a seat in that institution.

Phillip’s clientele included the acclaimed furniture designer Fred Lowen, whom Baer referred to Phillip, having known Lowen from their internment days. Henry Hirsch and Helmut Newton, the latter until he left for Europe, were others of Phillip’s clientele. Newton approached Phillip to discuss a job offer he had received from Vogue in Paris; the opportunity launched Newton to international fame. When Hirsch, a furniture manufacturer, ran into debt in the 1960s, Phillip was able to save many of his assets. Even Julian Layton, the Home Office representative who helped so many Dunera internees out of internment, crossed Phillip’s path. Layton had resumed work as a stockbroker after the war, and approached Phillip regarding the investments of the Hon. Mrs Lane—a Rothschild by descent and a client of Phillip’s.

According to Phillip, none of the Dunera boys volunteered information as to how they had ended up in Australia or spoke of their internment. ‘So I had these connections with no knowledge or intent, I wasn’t like… I’m going to get all these Dunera boys as clients’, Phillip laughs. ‘They just happened to be in my path as I went through life.’ Professional relationships turned into decades-long friendships.

Why was internment never mentioned? ‘They were never really imposed on by their early history’, Phillip recalls. ‘A bit like childhood: if you go to a school that you don’t like and has been horrible, you leave it but you move on. They all seem to have moved on’. No one identified as a former internee. Though Phillip readily believes the journey, in particular, was harrowing, as far as he can remember no one really mentioned that period, let alone described it as a severely damaging experience.

‘The other thing was that, at that time, there were no mobile phones, no googling’, Phillip adds with a wry smile. There was greater freedom to part with the earlier story of your life and in a sense, remake yourself.

There is no one point, Phillip says, that marks the moment he became truly cognizant of the shared history of these men to whom he had grown close. He struggles to pinpoint when it happened, suggesting initially that it may have been while reading Cyril Pearl’s The Dunera Scandal (1983). He pauses for a moment and then shakes his head: no, he must have already had some inkling, otherwise he likely wouldn't have picked up the book in the first place. He describes the process as one of ‘osmosis’ rather than any one moment of illumination.

Phillip reflects that it is more the descendants of the Dunera generation, their children and grandchildren, who are eager to carry on the remembrance. That said, he intervenes to correct information where he sees errors. An exhibition featuring the work of Henry Talbot included information Phillip recognised to be false; his call to the curator to offer corrections was rebuffed. On being asked whether he sees himself as a sort of Dunera fact-checker, he shakes his head. Not in general, he says, but in his good friend Talbot’s case, ‘who knew him better than I?’

Author: Georgina Rychner & Kate Garrett