‘At the time of his death, he was not just a father but a close friend,’ recalls Justin Zobel, sitting at the circular table in his brightly lit office at the University of Melbourne. It's an unexpected way to speak of one's stepfather.

Justin is referring to the late Werner Pelz: scholar, writer, priest and mentor.

Werner Pelz was born in Berlin in 1921, the son of a self-made Jewish entrepreneur, Ludwig Pelz. The Pelz family's riches to rags story mirrors that of many of their contemporaries, with Werner's childhood of expensive clothing and holidays at Lake Garda in Italy changed forever after the punitive Nuremberg Laws choked the family's wealth and, in less than a decade, saw them reduced to living in a dingy apartment in one of Berlin's most unsavoury neighbourhoods.

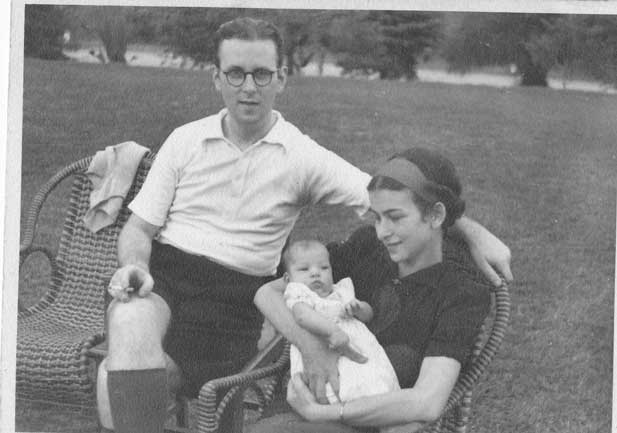

Werner as a young child at the height of his family's wealth. Pictured here with his younger sister Jutta and their mother Regina.

Werner as a young child at the height of his family's wealth. Pictured here with his younger sister Jutta and their mother Regina.

Awoken on the night of 9 November 1938 to the sound of breaking glass, the Pelz family listened as the Jewish-owned shop below their first-floor apartment was looted. Following Kristallnacht, Ludwig and Regina abandoned their attempts to salvage the family's former way of life and focussed their attention on ensuring their children's safety.

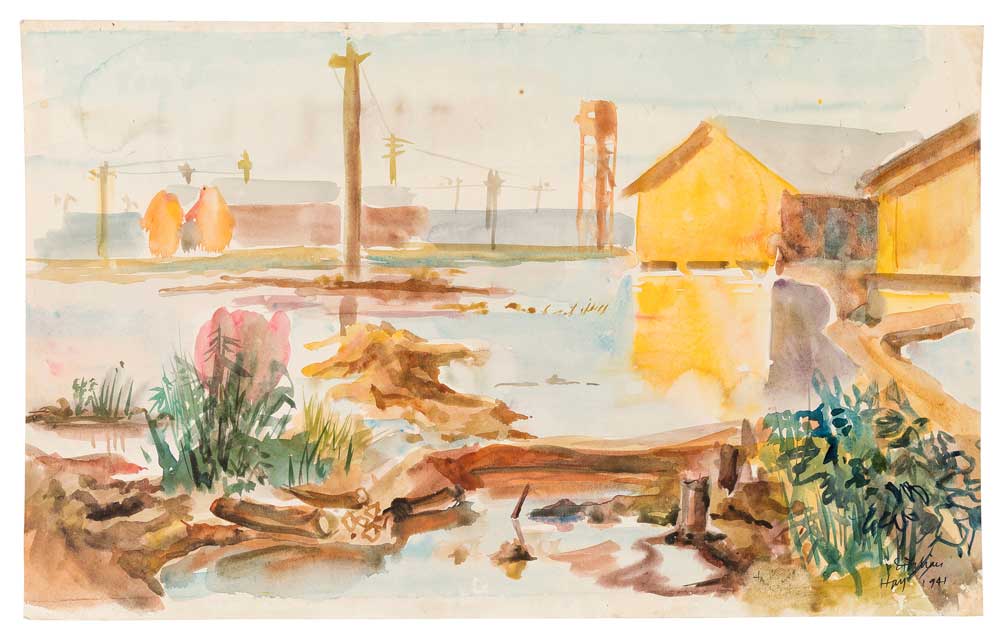

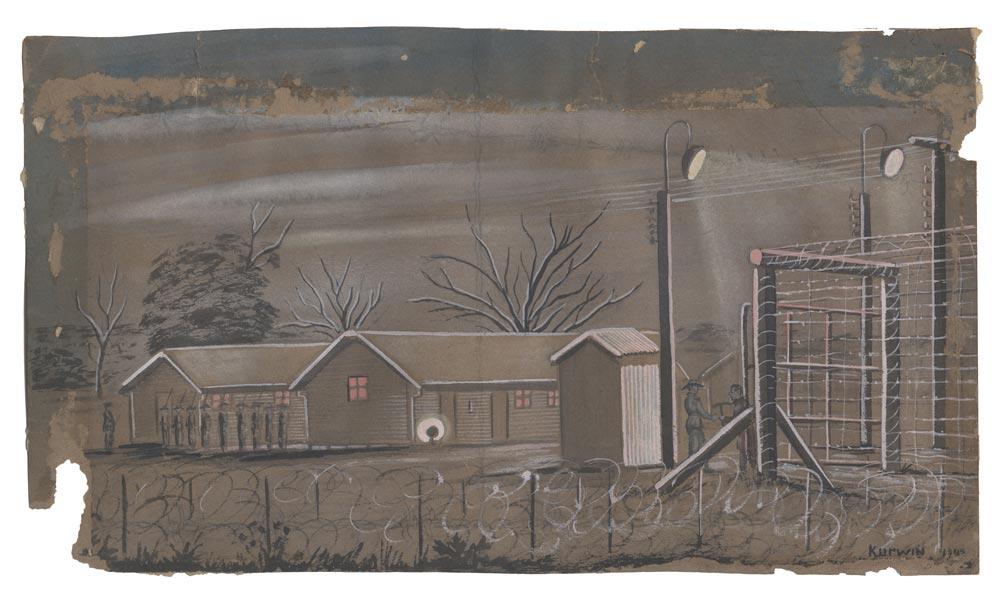

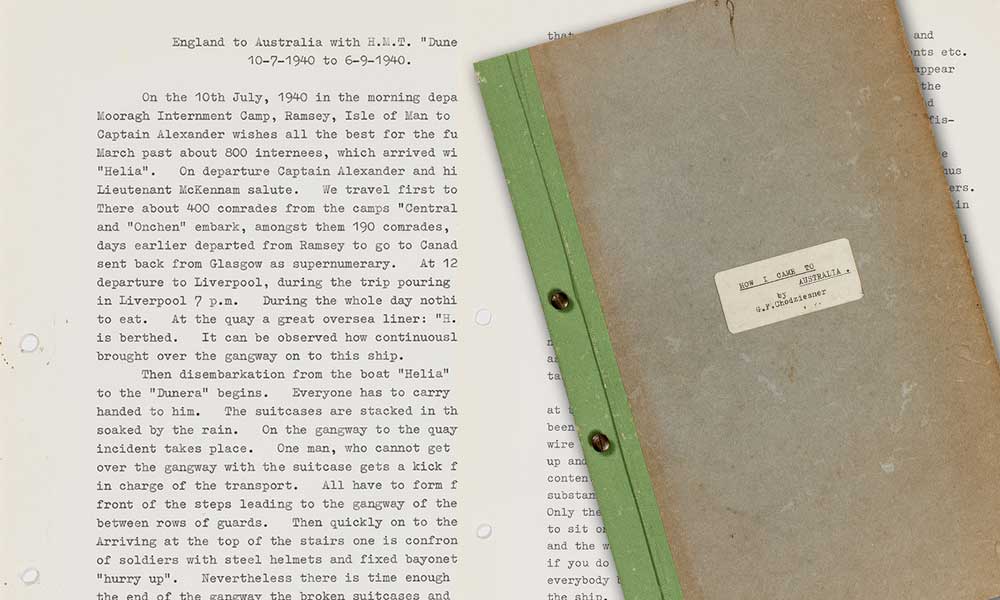

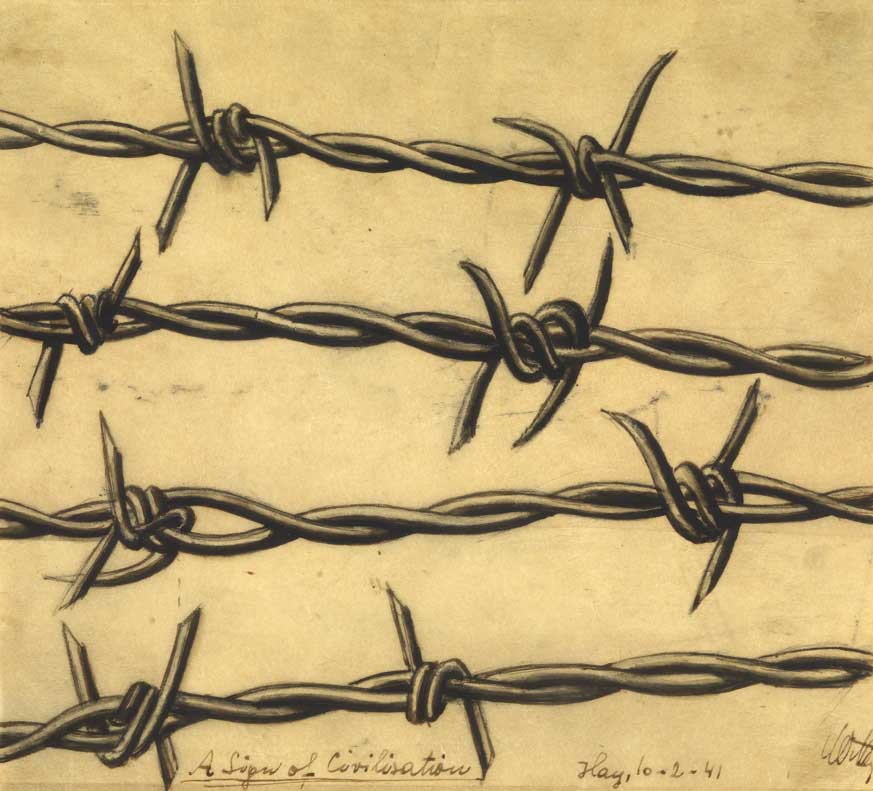

Werner, although drawn to study, began a farm-training program in the country, with a view to seeking asylum as a skilled farmworker. The following years took him to England, before he was swept up and transported halfway across the world to internment camps in Hay, New South Wales and then Tatura, Victoria. In Tatura, he converted to Christianity, which would become central to his later life.

Werner in the 1940s around the time of his return to Britain.

Werner in the 1940s around the time of his return to Britain.

In 1943, after being released from internment, but with the war still in full swing, Werner returned to England. He lived there for over three decades, before returning to Australia in the early 1970s to take up a post as a lecturer in sociology at La Trobe University – this time with his second wife, Mary Zobel, and her children, Daniel, Imogen and Justin.

Justin remembers those first years with Werner as difficult. His own father, Andrew Zobel, was from a wealthy Dresden family. In the late 1930s, Andrew fled with his mother to England. She was interned on the Isle of Man, while he was sent to Canada to be interned.

Andrew's premature death shattered his wife, Mary, and for Justin, who was born after his father's death, Andrew became a ghostly presence. ‘My mother idolised him after his death,’ remembers Justin, which, some years later, made it difficult for Werner to be accepted as his stepfather. This was the first time, says Justin, that it was clear that Andrew’s ghost was unreal.

Werner's relationship with ‘Germanness’ and the German language – both his mother tongue, and the language of his persecutors – was a complicated one. He and his first wife, Berlin-born Lotte Hensl, largely rejected German, speaking and writing only in English during their life together in England. Werner’s post-war life seems almost to be a study in Englishness. Following his adoption of Christianity during the war, he became an Anglican vicar, with a parish on the outskirts of a small regional town; he was a Guardian columnist, and for many years regularly appeared on BBC radio and television. In this same period, his belief in Christianity began to fade. He spent time on a kibbutz in Israel, and on the radio discussed Kafka and Nietzsche.

Later, though, his feelings towards ‘Germanness’ would be better characterised as a loss rather than a rejection. Justin remembers Werner's extensive collection of German books; his fondness for Wagner, overtly connected, for many, with the Nazis; his penchant for reading and translating German poetry, and his interest in German scholarship and philosophy, including the philosophers who had come to be seen as enablers of Nazism. German culture was often discussed at the dinner table, Justin remembers.

Werner's study in Montmorency where he sat for many hours a week.

Werner's study in Montmorency where he sat for many hours a week.

The trauma of his experiences as a result of the Nazi regime also hung over the dinner table: Werner's persecution and internment as a young man were a salient part of his later life. For some former internees, Australia was never anything more than a place of internment, but this was a notion Werner summarily rejected. Werner felt safe and accepted in Australia, Justin says, in a way he hadn’t known anywhere else – certainly not in Britain, where his German surname, accent, and olive skin had made him the victim of discrimination. And yet, like so many of his contemporaries, Werner was afflicted with survivor's guilt. His return to the UK in 1943, while the country was still at war, was at least partially prompted by the guilt he felt.

Though Werner rarely spoke of the family he was forced to leave behind, Justin did meet Werner's sister, Jutta, a handful of times. Though she, too, had left their childhood home to join the farm training program, she did not manage to escape Germany. She was imprisoned in Auschwitz and survived the death march to Ravensbrück before being liberated in 1945. In May 1943, Werner received one final note his parents had managed to send him, before they too were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered.

One other person from Werner's past also stands out in Justin's memory: Frieda, a former maid, who worked for the Pelz family in Berlin until Kristallnacht, when she and her husband were forced to flee Germany because they had been working for a Jewish family. They escaped to the East, crossing through Russia and then China, before eventually also settling in Melbourne. Justin met Frieda again after she happened to tune into a radio program featuring Werner and, remembering the son of her former employers, contacted him.

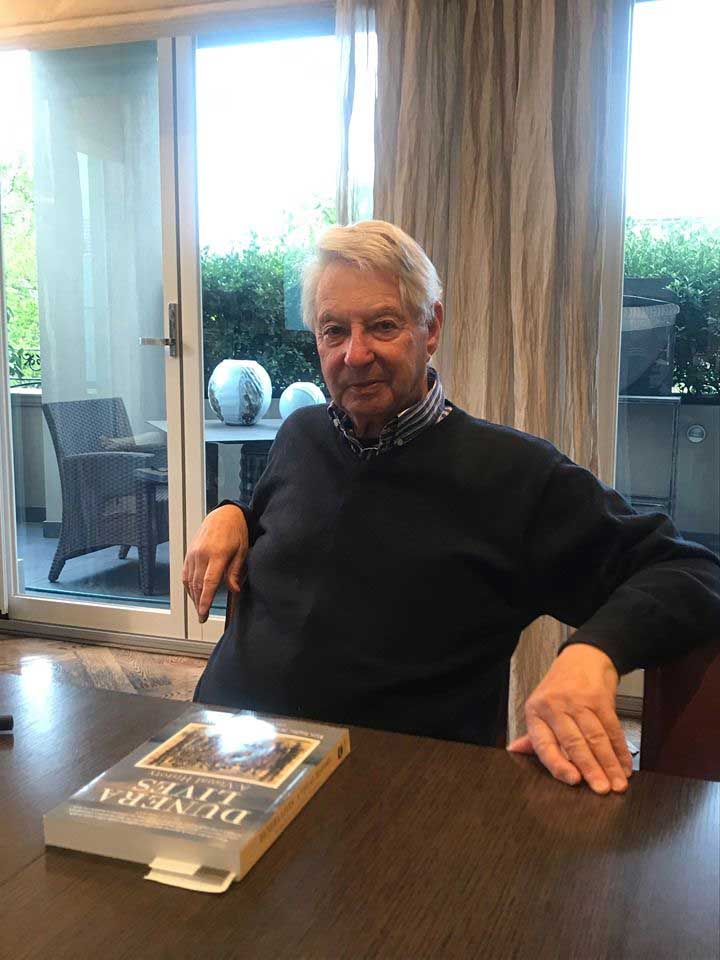

Justin with his stepfather 1970s.

Justin with his stepfather 1970s.

Those rocky early years with Werner gave way to cycles of friendship and conflict, as Justin grew up. Werner adored classical music and rejected anything contemporary, which caused tension with teenage Justin, who had taken to building stereos and playing modern music at home. Yet he and Justin also enjoyed activities together: they both loved being in the bush. From the time of his internment, Werner was delighted by the Australian countryside.

Justin left home at eighteen and was not close to his parents as a young adult. It wasn't until, at 24, he began a relationship with someone who got along well with Werner that Justin was able to see him through new eyes and to begin to appreciate him. This was a turning point in their relationship, and over the years they grew closer, each becoming the other's valued confidant.

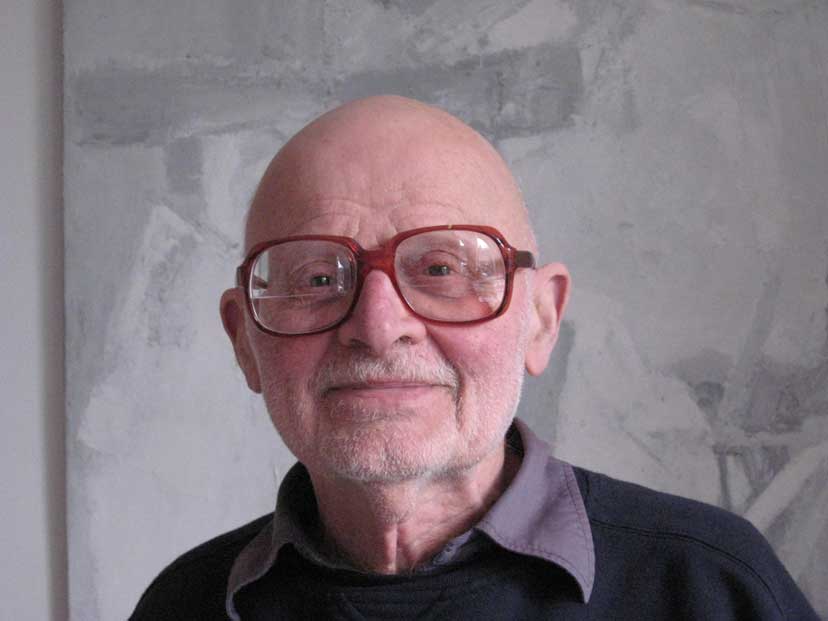

Werner in December 2005.

Werner in December 2005.

Werner continued to teach until 2004, two years before his death at age 84. Justin, too, has devoted his life to education. He is a Professor and Pro Vice-Chancellor at the University of Melbourne.

Note: a previous version of this article stated that the family of Andrew Zobel was left largely undisturbed by the Nazis until the late 1930s. New information has come to light indicating this may not have been the case, and the article has been updated accordingly.

All images © Justin Zobel

Author: Kate Garrett