Tuesday 11 June 1940. My father was woken by a knock on the door of his mother’s house in Reading, England. Two plain-clothes policemen had come to arrest him and his brother John, Italian citizens, as enemy aliens, the day after Italy had joined the Second World War on the side of the Axis. My father would not return home for five years.

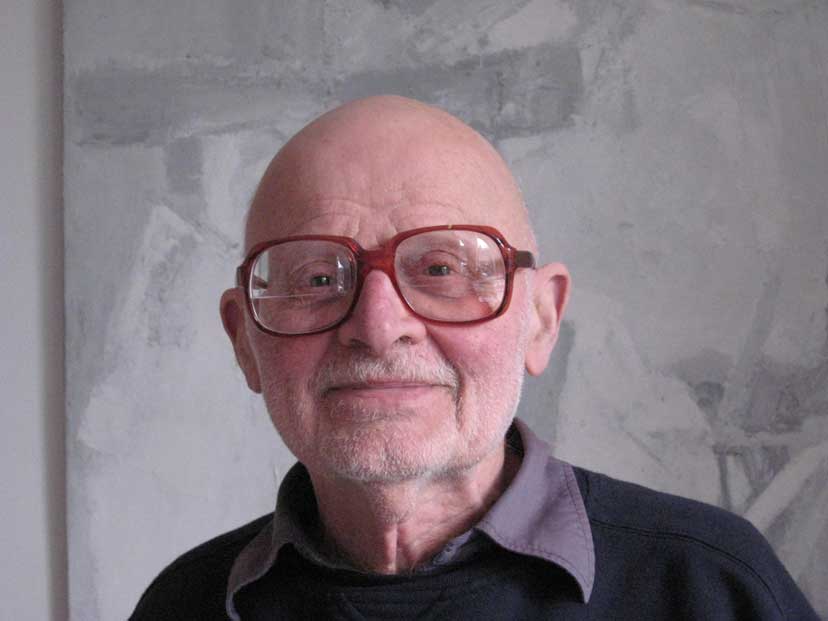

My father Giorgio Scola and my uncle John were born in San Remo, a coastal town in north-west Italy, but had lived and been schooled in England since 1921, when Giorgio was five. Their parents had migrated to Britain for work. My father was well educated – only months away from completing his architecture studies when he was arrested – and kept a diary of his internment. This article quotes extensively from his diary.

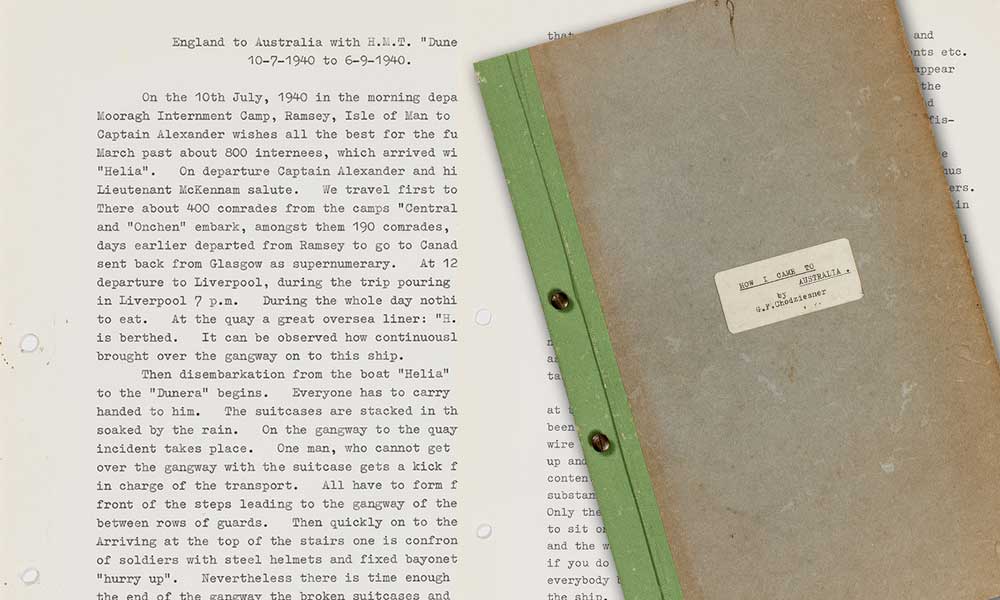

Giorgio and John were taken together to a series of temporary internment camps in England, then were separated after three weeks. At the end of June 1940, my father was deported to Canada on the Arandora Star, which was torpedoed and sunk with the loss of over 800 lives; he was rescued at sea. Being younger and fitter than most of the Italians aboard probably helped. A little over a week later, and to my father’s horror, he was taken to the same dock where he had started his ill-fated Arandora Star voyage and deported again, this time on the Dunera, bound for Australia. He described the scene: ‘before going up the gangway we are one by one roughly manhandled and not only our belongings, but our person is minutely searched, and the contents of our pockets ruthlessly emptied. Any word of protest is greeted by a blow of some sort, even officers taking part.’

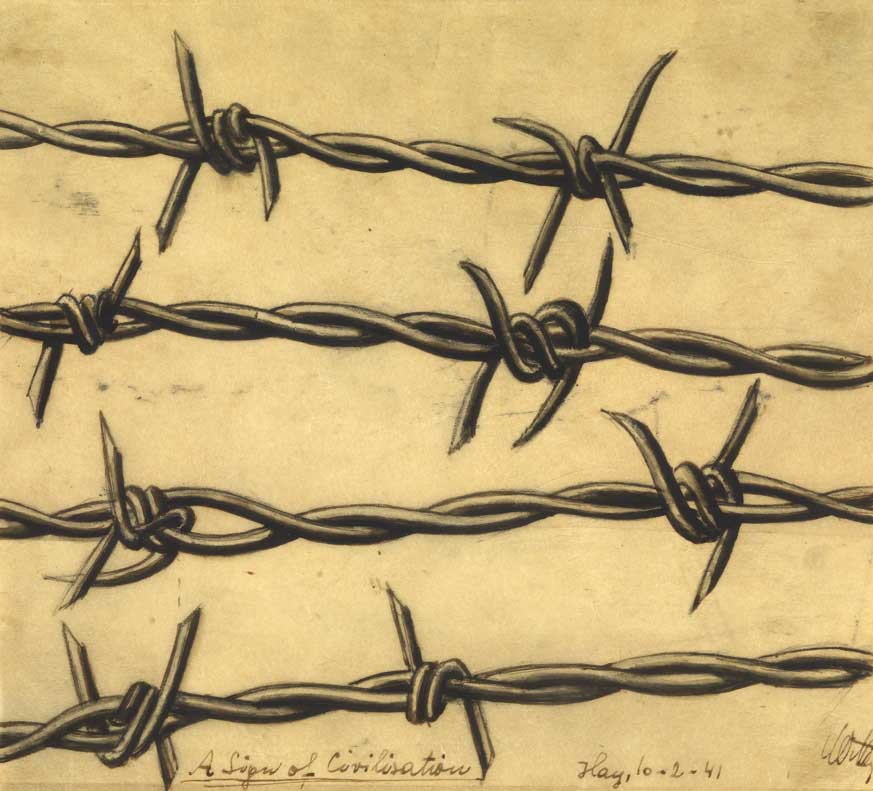

On board the Dunera, Giorgio remembered ‘over 200 of us in a space about 50 ft x 30 ft x 7 ft in height. On a lower deck little more than a corridor serving also as a gangway is provided to enable several hundred of us to see the light of day and to get some fresh air – this space is enclosed .. with barbed wire so that any hope of escape is slight. We look round our stuffy prison with looks of despair – perhaps a fortnight under these conditions, coupled with considerable danger, makes the future look pretty black. Whilst thinking in this vein a clique of sergeants and soldiers begin a further search of us and everything we may have left.... all cigarettes, valuables, money, rings, paper and toilet necessities are flung on the floor and then collected by a gang of soldiers into sacks!’

The following day, Friday 12 July, he recorded: ‘Some time after breakfast when most of us ... hear a loud explosion, quickly followed by another – our nerves already on edge with the previous experience. One and all make a rush for the door at the head of the stairs, which is found to be locked – there are shouts and cries but all to no avail until two or three men get hold of a piece of wood and attempt to batter down some wooden panels. The air is stifling, and I am almost crushed – everyone fears the worse: that we are sinking and that we won't have a chance to escape. The ram breaks through and as one man is starting to get through to the deck, several soldiers rush up pointing fixed bayonets through the opening and tell us to calm down as everything is alright – none of us believe them and refuse to go down, at which one threatens to fire.’ According to the 1980 book Collar the Lot by Peter and Leni Gillman, ‘By only a fraction did the Dunera avoid sharing the fate of the Arandora Star. Moments after the U-56 fired, Oberleutnant Harms observed the Dunera make a 40° turn to starboard. It is clear that the turn was merely a standard precautionary manoeuvre, and not the result of a lookout’s warning.’

Initially the Dunera internees did not know their destination, though eventually they realised they were not headed to Canada, but Australia. Besides the well-documented theft and violence perpetrated by the military guards, and the overcrowded and insanitary conditions, my father suffered from the rough seas and boredom: ‘We begin to settle down to the unbearably monotonous routine’, he wrote, and later: ‘I am counting the days to the end of this apparently interminable voyage ... and I am quite sick of the sea.’ Five weeks into the voyage, he complained about the ‘confinement and monotony’: ‘I feel terribly tired as I haven't slept for several nights and am quite fed up’.

The Dunera reached Fremantle in late August 1940, then sailed to Melbourne: ‘Here about 600, including refugees, Nazis and ourselves, land while the rest are to proceed to Sydney.’ Aboard the train, the Australian troops assigned to guard the internees ‘greet us more as strangers than as enemies’. ‘Even before we leave the quayside station, the soldier sitting on my right has handed round cigarettes rolled by himself to anyone who wants them. He is almost sympathetic when he hears our story.’

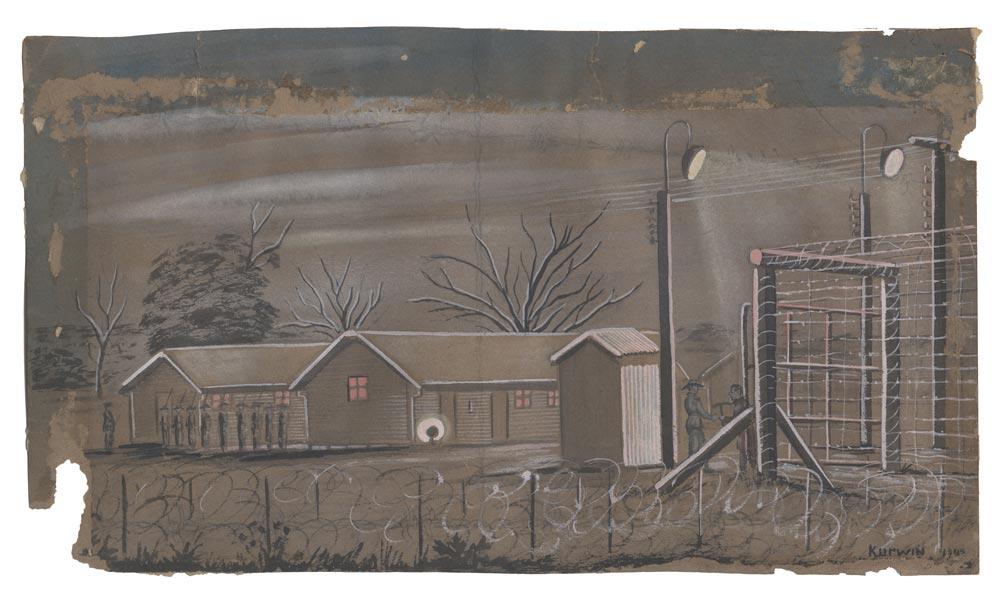

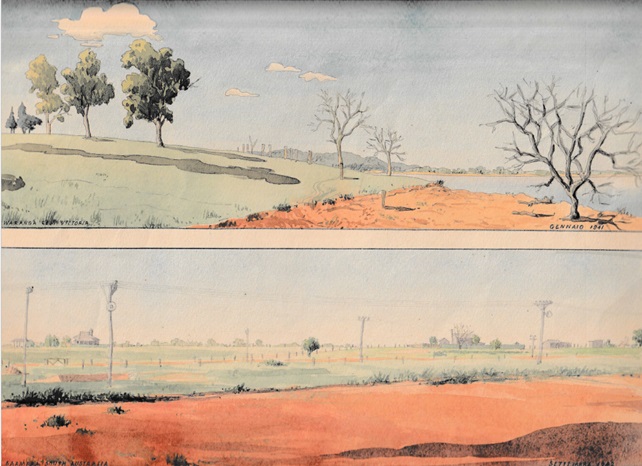

My father was taken to the Tatura internment complex in central Victoria, where he stayed until December 1941 when he was moved to Loveday camp, at Barmera in the South Australian Riverland. In September 1942 he was moved back to Camp 2 at Tatura, ‘which we believe to be a transit camp for those due for release’. He was mistaken on both counts, for Camp 2 was not a transit camp, and he wasn’t due for release. His application for a permit to return to Britain was refused, and he returned to Loveday in February 1944. Finally, on Christmas Eve 1944, he received permission to return to Britain, though transport had first to be arranged.

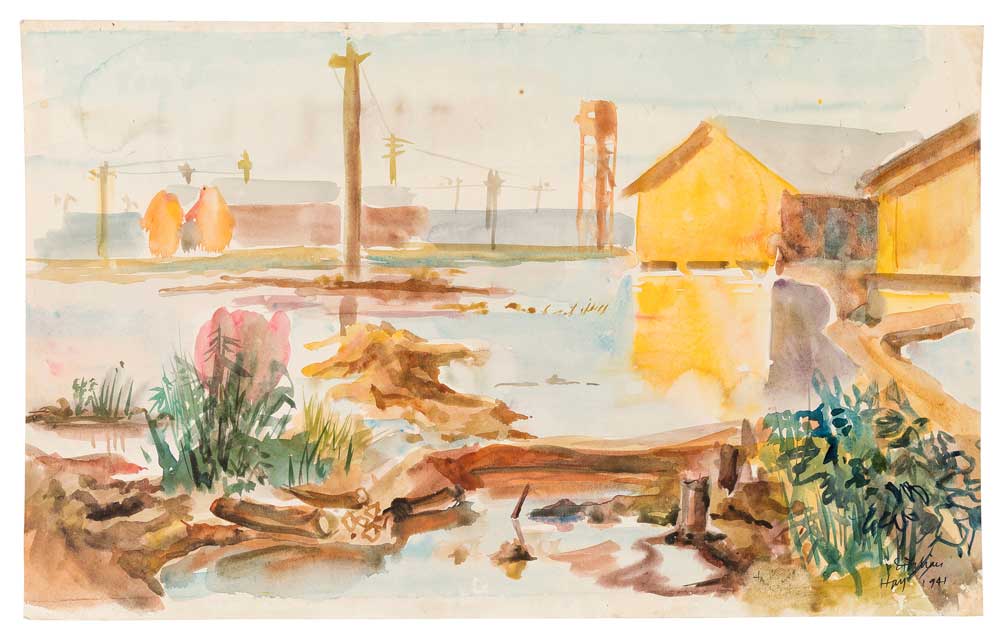

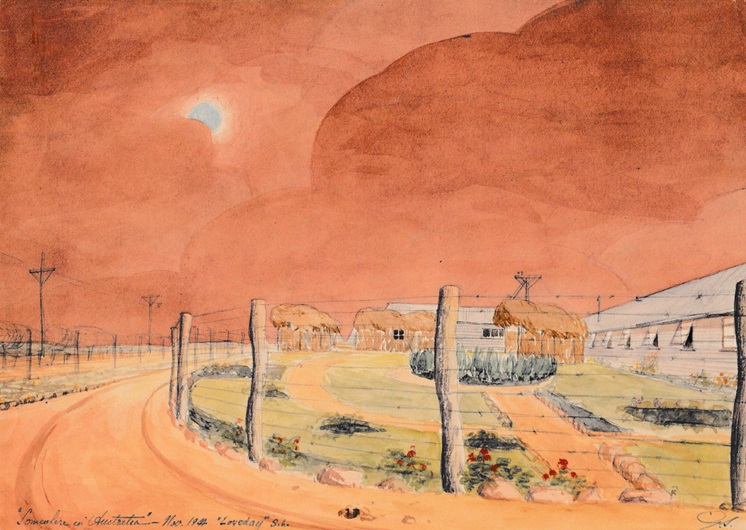

A watercolour by Giorgio Scola, entitled 'Somewhere in Australia', completed in Loveday, South Australia.

A watercolour by Giorgio Scola, entitled 'Somewhere in Australia', completed in Loveday, South Australia.

In January 1945 he returned to Tatura, and in February to ‘a tented camp outside Sydney’ (Liverpool transit camp) until boarding the Dominion Monarch on 5 March 1945. After his arrival at Liverpool, England, in mid-April, he was held for a further four months on the Isle of Man before being released from internment.

His brother John had endured a shorter period of internment. After being transported to Canada in 1940, then held there, he was allowed to return to Britain in March 1941, and was released that June. In the 1950s he moved to Milan to teach English, returning to Britain on his retirement. John died in 1996.

One reason for my father’s late release, and for his deportation, was that he was a member of the London Branch of the Italian Fascist Party (although many of those deported were neither Nazis nor fascists, but refugees and others with no interest in politics). His Australian conduct report of January 1945 states: ‘Since his return to Tatura his behaviour has been good. His outlook appears to have changed and does not openly show fascist leanings as was the case prior to his transfer to Loveday.’

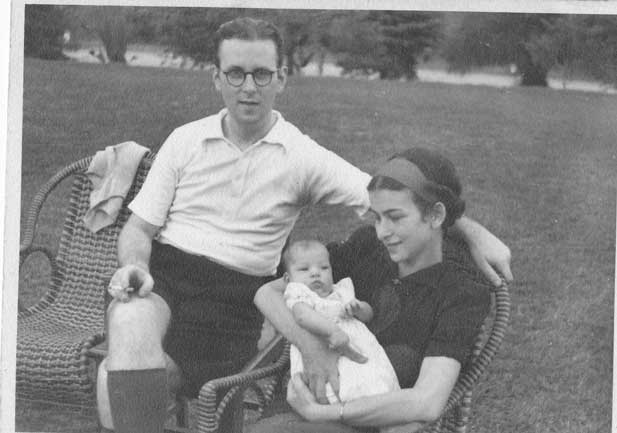

He worked surveying sites until getting a job with the British civil service as a draughtsman, then as an Assistant Architect in Public Works. He married an Italian, my mother Fiammetta Cattaneo, in 1950, was naturalised British – swearing an oath of allegiance to the Queen – and had three children: my brother Charles, sister Marina, and me. We enjoyed a loving upbringing, went to Catholic Church every Sunday, and to Italy every summer to see our grandmother, relatives and our mother’s friends.

My father lived a family-oriented life, indulging his passion for travel, cathedrals and classical music. He never returned to Australia and almost never discussed his wartime experiences. He died in 2006 aged 89, survived by his wife, three married adult children, and seven grandchildren.

An edited and illustrated version of Giorgio Scola’s diary is available here to download for free.

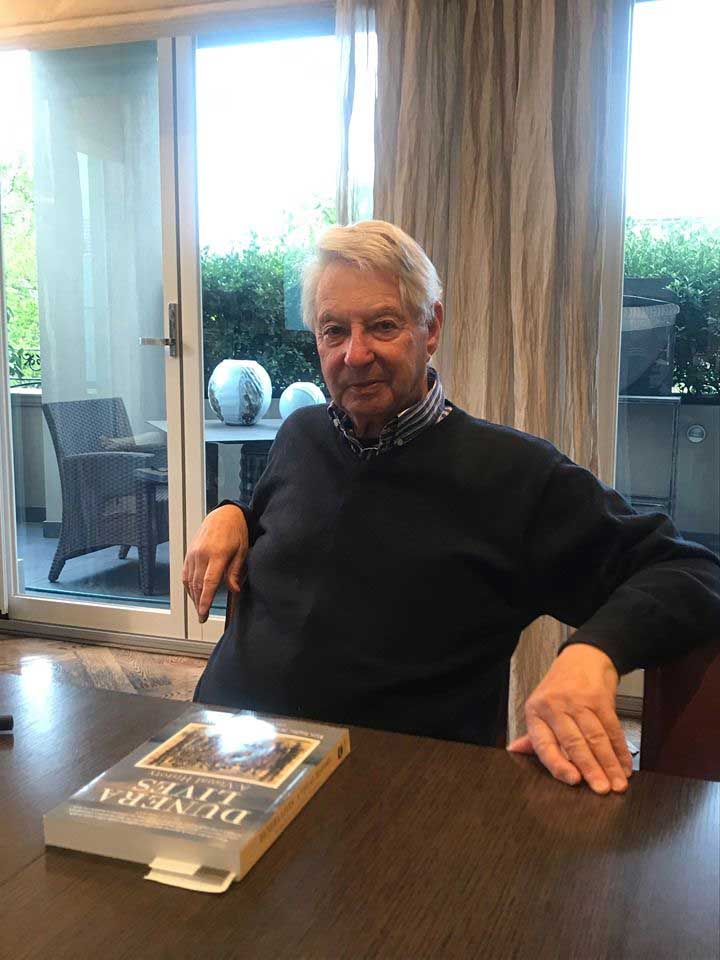

Author: Julian Scola