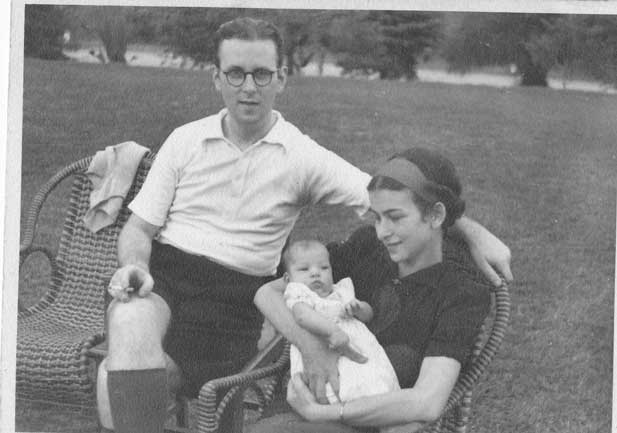

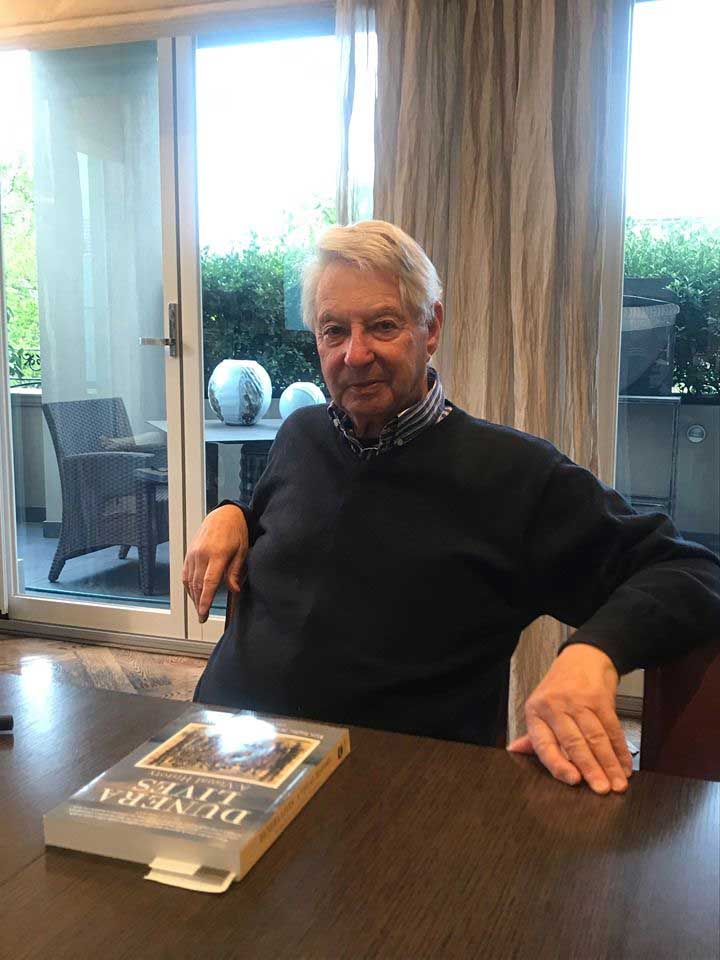

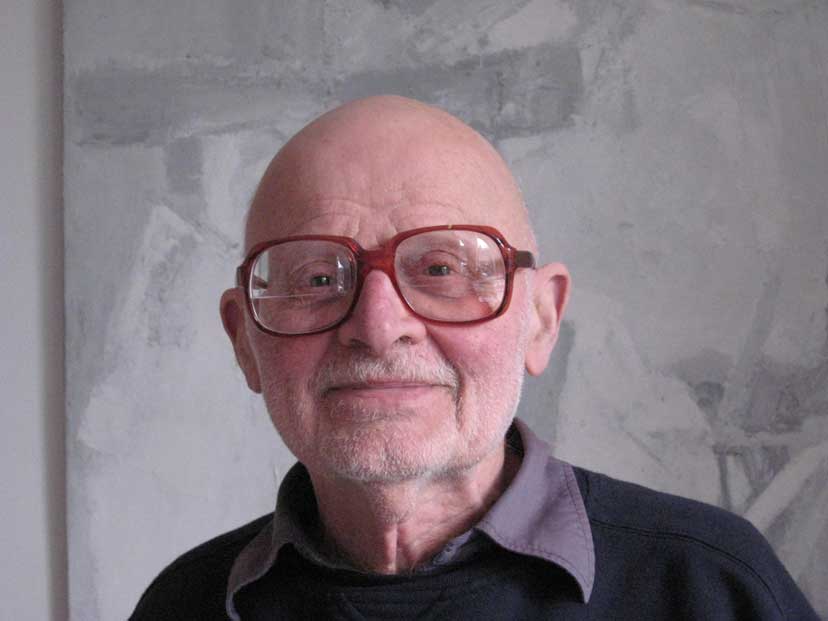

Günter and Paul Altmann, image © Margaret Riederer.

Günter and Paul Altmann, image © Margaret Riederer.The story of the Dunera internees often is told as an Australian one, which is misleading. As the scholar Carol Bunyan has established, just over 600, or about a quarter, of the Dunera internees remained in Australia. This tendency to use an Australian lens can obscure the degree to which the story is global, touching people and places across continents.

The Altmann brothers were born in Düsseldorf, Paul on 11 August 1917 and Günter the following year, on 28 December. Paul was the second of seven children born to Oscar and Margarete, Günter the third. Oscar and Margarete (nee Bernhard) had married during the First World War, when Oscar was on leave from frontline service with the German Army. The war cost Oscar the lower part of one of his legs. After the war, he became a director of Mannesmann, a major iron and steel company in Düsseldorf, and this occupation provided his family with a prosperous life. Oscar was of Jewish heritage, as was Margarete, but in common with so many Jewish Germans of the time, their ties to Judaism were of the past rather than the present. They were devoted Lutherans, and their seven children were baptised into the Lutheran church.

With the rise of Nazism, many Germans of Jewish heritage thought initially that patriotism would protect them from Nazi prejudice. Surely past war service, for instance, would be taken as proof of their loyalty? Tragically, some clung to this hope until it was too late to escape. Their faith in sanity and reason became their condemnation. At one time Oscar too, had thought of patriotism and good citizenship as a bulwark, but his dismissal from Mannesmann in 1936 and threats of arrest made him realise that the Altmann family would never be safe in Nazi Germany. He decided to emigrate, and eventually settled on Brazil. He, Margarete, and their two youngest children, Gabriele and Friedrich (Fritz), escaped Germany for South America in June 1939. One of Margarete’s sisters was later murdered in a concentration camp.

Between his dismissal from Mannesmann and departure for Brazil, Oscar had produced a volume entitled ‘Familien-Erinnerungen’ (family memories). Written with Margarete, the self-published volume is a history of the Altmann family, penned for their children. The volume is beautifully produced, printed on thick paper, and attractively bound. If it were a gift for the Altmann children, was it also a testimony, a document to ensure that the history of the Altmanns outlasted the Nazi regime, even if the family did not? The volume stands as a monument to pride and defiance.

While Oscar and Margarete did not have sufficient money to pay for all of their family to travel to Brazil, there was comfort in the fact that the five elder children – Gertrud, Paul, Günter, Hildegard and Helene (Leni) – were safely in Britain, along with their paternal grandmother Helene, known affectionately as Oma Lenchen. Paul had moved to London in July 1936 to begin a steelworks apprenticeship and engineering studies, possibilities closed to him in Germany by virtue of his Jewish heritage. Ultimately British residency proved a double blessing, for it provided both safe haven and contact with the Quakers, through whom Paul was able to secure visas for Gertrud, Hildegard, Leni and Oma Lenchen to travel to Britain.

Günter’s route to Britain was more circuitous. On 30 April 1937 he had left Germany for Italy, where he studied farm administration. Possibly he lived in or near Milan, for he attended opera performances at La Scala. Günter had dreamt of being a musician or conductor – he could play instruments by ear – but Nazi curbs on cultural activities had quelled that ambition. In March 1939 he moved from Italy to Britain. Possibly his British visa was organised by Paul, though this is unclear. These few details are all that Margaret Riederer, Günter’s daughter, knows of her father’s time in Italy.

Günter was arrested on 3 June 1940 in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, where he worked as a farm labourer. Paul, who had recently completed his degree studies in electrical engineering at the University of London, was arrested in that city on 27 June 1940. But neither brother knew the other’s fate until, by chance, they met aboard the Dunera. ‘We had not heard from each other’, Paul wrote, ‘and it was a pleasant surprise’. For some men on the Dunera, the presence of another family member proved a salvation, a crucial support in trying times. But for Günter and Paul, their meeting proved little more than the ‘pleasant surprise’ Paul described. The brothers had never been close, and as Paul recalled, they went ‘separate ways on the ship and later.’

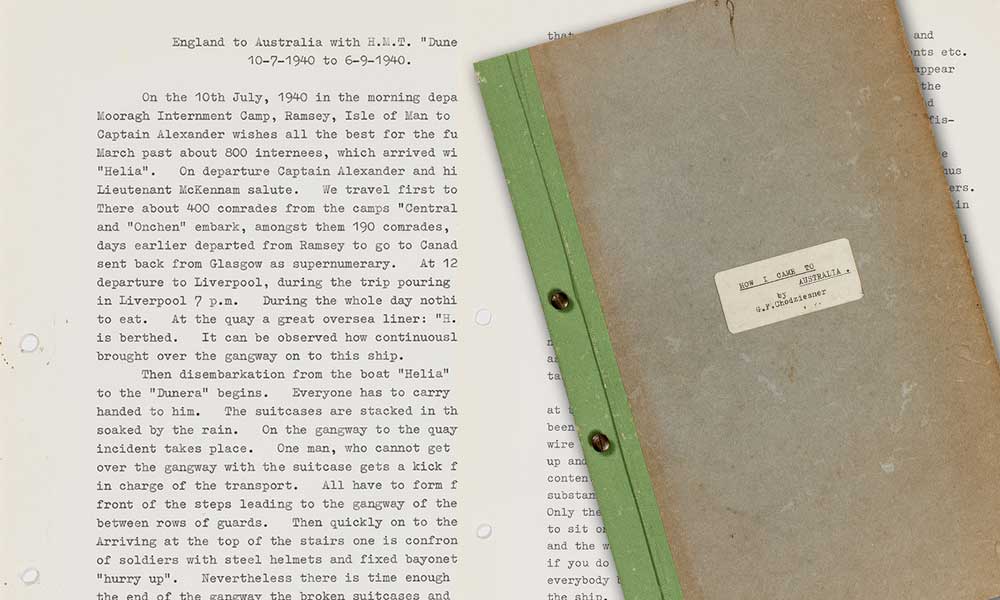

Both Paul and Günter documented their experiences on the Dunera. Paul did so briefly, in his family memoir written in 2001. His account of the voyage tells of the appalling treatment of the internees by their British captors, and of brighter moments – friendships formed, knowledge gained, music enjoyed – that leavened distress. His valuable testimony might be described as conventional, in that it echoes the form and tone adopted by other Dunera memoirists.

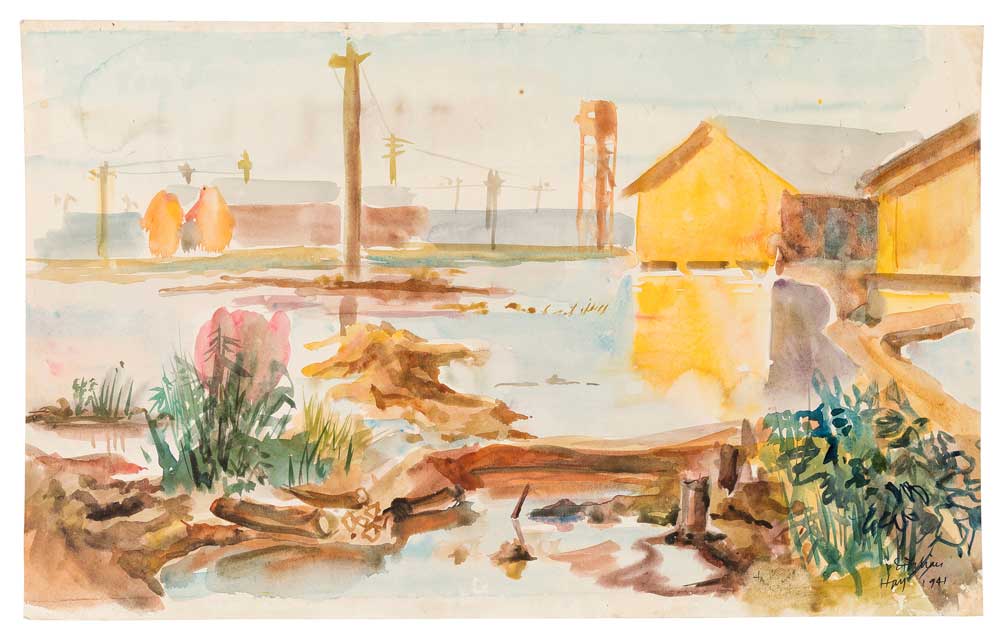

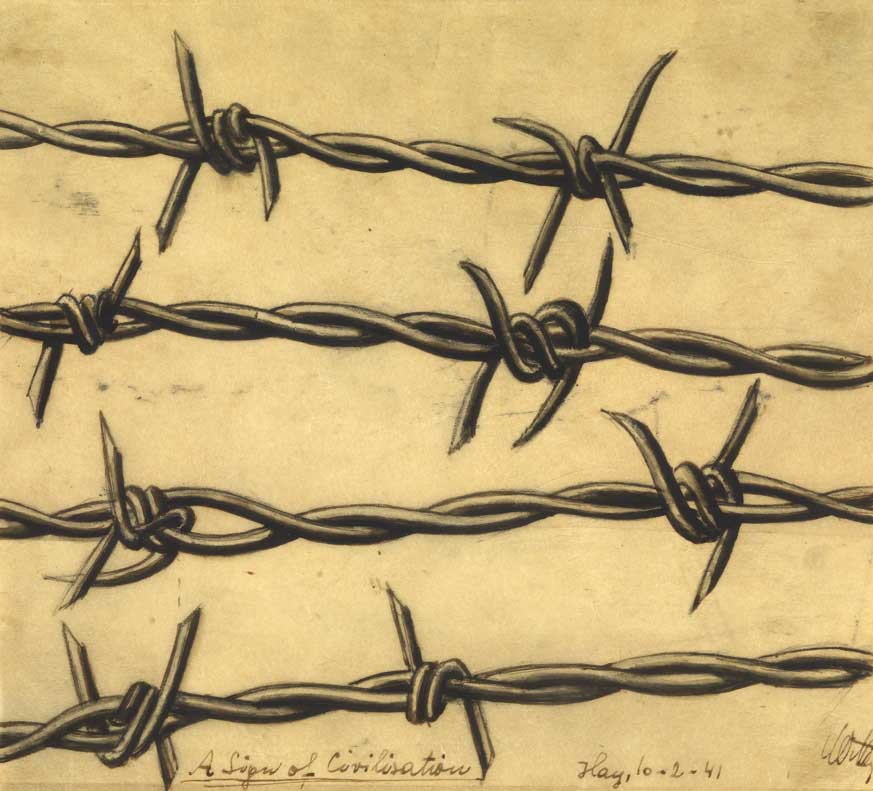

Günter’s account also is valuable, and unconventional. Written in German during Easter 1941, his account is more testimony than memoir. Several Dunera men wrote long accounts of the voyage, essentially as a record for posterity, but few with a touch as dry and astute as that which Günter brought to his writing. Indeed, the document is unusual for its wide-ranging perspective. Günter writes of perfidy among the British guards, as might be expected, but also of poor behaviour among internees. He laments that the internees were not united by their suffering and plight: ‘Not even the danger we constantly faced, nor the collective awareness of the injustice that had happened to us could bring us together such that we would be spared at least the friction of everyday life.’ This is not the substance on which Dunera histories have been built. Other uncommon elements of Günter’s testimony include mention of a few British guards who showed decency and kindness, and of the internees’ brush with the White Australia policy. When the Dunera docked at Fremantle on 27 August, Günter recalled an Australian bureaucrat boarding the ship to determine if men of Black or Japanese heritage were among the internees, and this at a time when Australia was not yet at war with Japan. Institutionalised racism deemed such men less tolerable even than German and Austrian Jews.

Günter’s dry observations are evident elsewhere. Soon after the Dunera left London, the German submarine U-56 fired torpedoes at the ship, without effect. Whether the torpedoes missed or failed to detonate remains a matter of conjecture, and considerable myth. Earlier than most, Günter was aware of the ‘wild’ and ‘fantastical’ elements that attend accounts of the incident, and the role internees played in fostering different versions of the tale.

One particular incident Günter did not mention. As he later confessed to family, on the Dunera he took a piece of bread from a sleeping mate. For a caring man predisposed to sharing and helping others, this act was not in character, and the shame tormented him. His daughter Margaret believes that the guilt Günter felt about this incident made him more generous, almost to a fault. She knew her father as a man who always shared with others, even when it meant taking from his family to do so. That the past could weigh heavily on Günter seems clear. He experienced a recurring nightmare in which he chased Hitler. Whenever he got close to catching him, Hitler escaped.

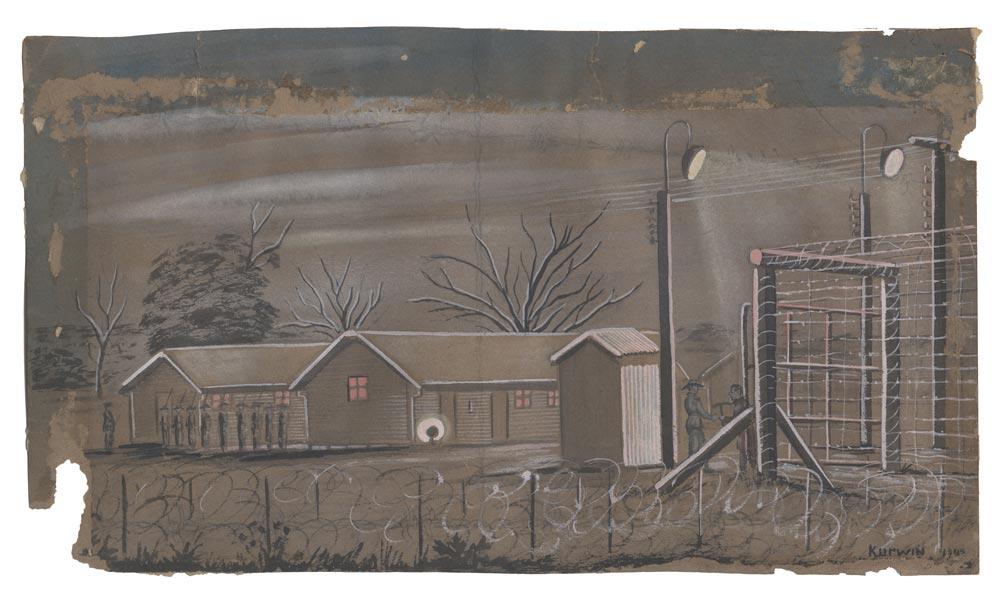

At Hay Camp 7, the brothers lived different lives, Paul in Hut 36 and Günter in Hut 24. Hut 36 was known informally as the Stadlen hut, named for its unofficial leader Peter Stadlen. Stadlen was a distinguished Viennese concert pianist, and Paul seems to have delighted in his company and the music that surrounded him. Another of Paul’s friends from Hut 36 was Heinz Tichauer, who would forge a productive and successful career as the photographer Henry Talbot. A third Dunera mate was the artist Fritz Schönbach, though almost certainly that friendship was born later at Tatura: Paul and Fritz were in different camps at Hay. To whom Günter was close is not known; his internment writings offer few strong clues.

Paul came to think of his time in Australian internment ‘as a very rewarding period of my life.’ While he warmed to Australia; Günter didn’t. But until the brothers won their freedom, any decisions about the future would have to wait.

In January 1942 the Australian government announced that Dunera men would be able to secure their freedom by enlisting in an employment company of the Australian Army. Günter registered his interest in enlisting on 30 January 1942. Paul followed soon after, on 15 March 1942. After a period spent picking fruit, the brothers’ Army service began in April, once the 8th Employment Company was raised. Paul’s time in the Army was brief, lasting only until August 1942. Almost certainly this was because Australian authorities recognised that Paul, as a qualified engineer, could serve the Australian war effort more usefully as a civilian. His Army service form mentions release for work in a reserved occupation; the British term was work of national importance. The fact that Paul had British rather than German qualifications almost certainly influenced this development. For Australian authorities involved in prosecuting the war, British qualifications were an indication, if not necessarily proof, of both competence and loyalty. Paul’s first Australian job was as an electrical draughtsman at Australian General Electric in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond.

With Australia feeling ever more like home, Paul determined to make an Australian life. He became a naturalised Australian on 11 September 1945, by which time he had met Suse, his love and future wife. Later Paul worked for Australian Paper Manufacturers in Fairfield, where several former Dunera internees were employed. Paul’s talents led to his becoming Chief Electrical Engineer at APM.

For Günter, who was younger and without Paul’s qualifications, the path to civilian life was longer and more convoluted. Günter served four years in the Australian Army until his demobilisation on 15 January 1946. The Altmann brothers had received permission to leave Australia for Brazil in 1941, but after the start of the Pacific War in December 1941 that authority essentially was theoretical. Only after the war had it become a clear possibility, and only Günter wished to act on it. Paul did visit Brazil and his family in the late 1940s, but had no intention of remaining there.

Günter had never felt welcome in Australia, and did not share Paul’s attraction to the possibilities of an Australian life. Exactly a week after Günter was demobilised, he left Australia on the Athlone Castle then, in the middle of 1946, sailed from Britain to Brazil on the Belgian Veteran. Finally, he was reunited with his parents and siblings, including his sisters Gertrud, Hildegard and Leni, as well as Oma Lenchen: they had managed to emigrate from Britain to Brazil during the war. Writing beside the Murray River at Tocumwal in September 1943, Günter had envisaged this moment:

There is a little farm in the heart of Brasil where Father and Mother are waiting for their boy to come and take off their hands the work of caring for the family that is, still, spread over distant parts of the world but will, one day, be reunited on the little farm, so[?] they hope.

The reunion of which Günter had dreamt had been realised, but at a cost: his new bride and baby daughter were still in Australia.

Around 1944, Günter had met Heather Margaret (Peggy) Harvey, a Tasmanian nurse working in Moe in Gippsland. Günter was stationed nearby, and family history has it that he was sent to the hospital to translate for an Italian prisoner-of-war. As well as English and German, Günter spoke Italian and some French. A relationship blossomed between Günter and Peggy, and soon she was pregnant, a development that prompted them to marry earlier than they might have. They married on 7 April 1945, and their daughter, named Margaret for her mother and grandmother, was born that September. If the conceiving of a child outside marriage was the stuff of scandal for some, not for Günter. He saw nothing to be ashamed of, and never concealed this fact from Margaret, on whom he doted.

But first came separation. Günter’s plan was to settle in Brazil, earn some money, then have Peggy and Margaret join him. Peggy would have preferred to live in Australia, but her parents insisted that she had a duty to keep her young family together. She and Margaret left Australia in November 1947, on the same ship that took Paul to Britain. Peggy was deeply reluctant to leave Australia, but Paul saw to it that she and Margaret made the ship. Mother and daughter arrived in Brazil at the start of 1948, and were reunited with Günter at Altmann’s farm, known as ‘Fazenda Margarida’, near Rolândia, in southern Brazil. Two years after their reunion, Günter and Peggy welcomed another daughter, Catherina, and soon the family moved to Mandaguari, elsewhere in Paraná state, where Günter worked as a manager for a company that processed and exported coffee. The company was owned by Hildegard’s husband, Günter’s brother-in-law. The family of Günter and Peggy grew with the addition of three boys: Jaime, Robert and Marcelo.

Both Günter and Peggy made brave concessions for their new, Brazilian lives. Peggy became fluent in Portuguese and created a life and family in Brazil. She also became reasonably proficient in German, the language of the family into which she had married. For Günter, his work in the coffee industry was a job rather than a calling; a job he undertook to support his young family. Later he worked for United Artists in Rio de Janeiro, and much later still as a translator. Günter came to translation in his early 60s, and in this work found reward and enjoyment, probably for the first time in his working life. Translation did not require him to be formal, or to have a head for business. Rather, the job asked him to dwell in the joys and beauty of language, which for a man with an ear and gift for different tongues was hardly a job at all. His translations into Portuguese included a Günter Grass novel, which sold well in Brazil.

Certainly, translation suited Günter’s intellectual gifts and disposition. ‘Dreamy, dreamy, dreamy’ is Margaret’s loving description of her father. Some, and perhaps many, of his dreams went unrealised, but it bothered others more than him. Günter’s lack of material success was a disappointment to his parents, though never for Margaret, who remembers him as a caring and wonderfully thoughtful father, always sensitive to her needs. Günter died in 1991, aged 72.

Peggy died in Brazil in April 2017, aged 95. In March 2020, Margaret and her Brazilian husband Carlos – the son of pre-war refugees from Vienna – emigrated to Melbourne. For Margaret and Carlos, their age was a factor in choosing Australia over staying in Brazil, and a desire to be closer to their children, although that possibility could only be partly realised: their daughter Marcia lives in Australia, their son Fernando in Vienna.

A sense of necessity had attended Peggy’s move to Brazil seventy-five years earlier, and a similar sense bore on the decision of Margaret and Carlos. Theirs was a choice born of pragmatism and love for family, rather than any particular interest in moving their home, for Australia held no great attraction. Margaret’s first return visit to Australia had come in 1993, when she was nearly 50. By then Australia was already a foreign land: her first language, English, now her third. Though fluent in English, the languages of her life had long been Portuguese and German. When Margaret returned to Australia permanently in 2020, she felt no connection to the country.

Though Margaret feels little affinity with Australia, there are comforts. She and Carlos are near Marcia, and Marcia’s children. Margaret’s brother Jaime, who has lived in Australia for the past twenty-five years, also is nearby. Close too are members of Margaret’s wider Australian family, including four Australian cousins from the Harvey side, and Ralph and Janis, Paul’s son and daughter-in-law. Paul died in 2005, aged 87.

Since returning to Australia, Margaret has learnt more about her father’s Dunera experiences and the history that took the Altmann family from Germany to Australia and beyond. In the international, intercontinental, story of the Altmann family, a new Australian chapter is being written.

Thanks to Margaret Riederer, and Ralph and Janis Altmann, for sharing their stories. Thanks to Carol Bunyan for expert advice.

Author: Seumas Spark