Günter Altmann was born on 28 December 1918 and was just 21 years old when he was detained in Britain and deported to Australia aboard the Dunera. And though his older brother, Paul Altmann, was also aboard, their lives up until then and in the years that followed would diverge in many ways: Paul and Günter had been living in different cities in Britain and were only reunited when, by happenstance, they were assigned to the same deck on board the Dunera; later, Paul chose to remain in Australia following internment, while Günter and his Australian wife joined his parents in Brazil.

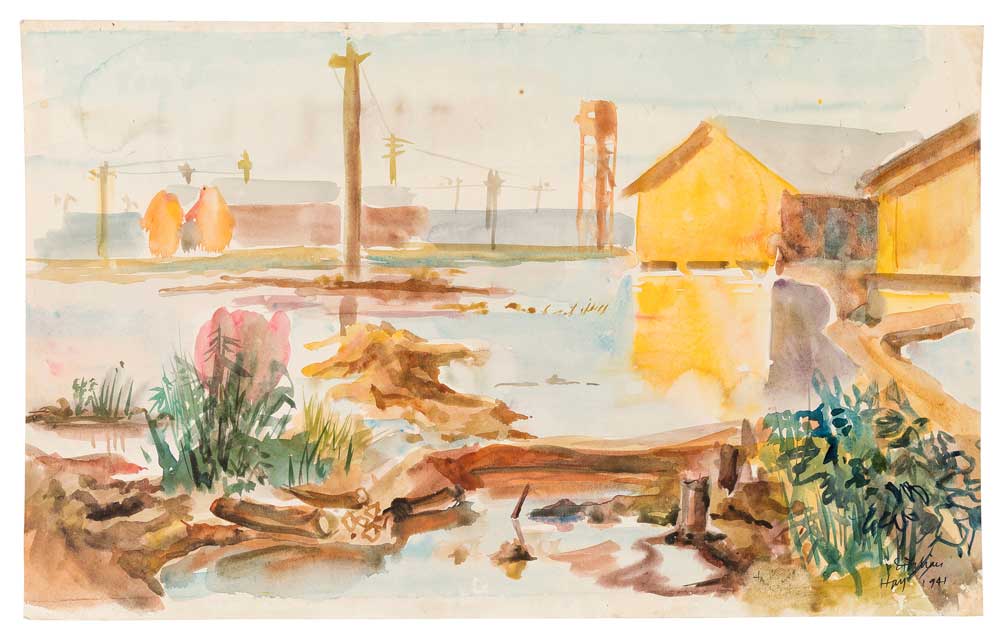

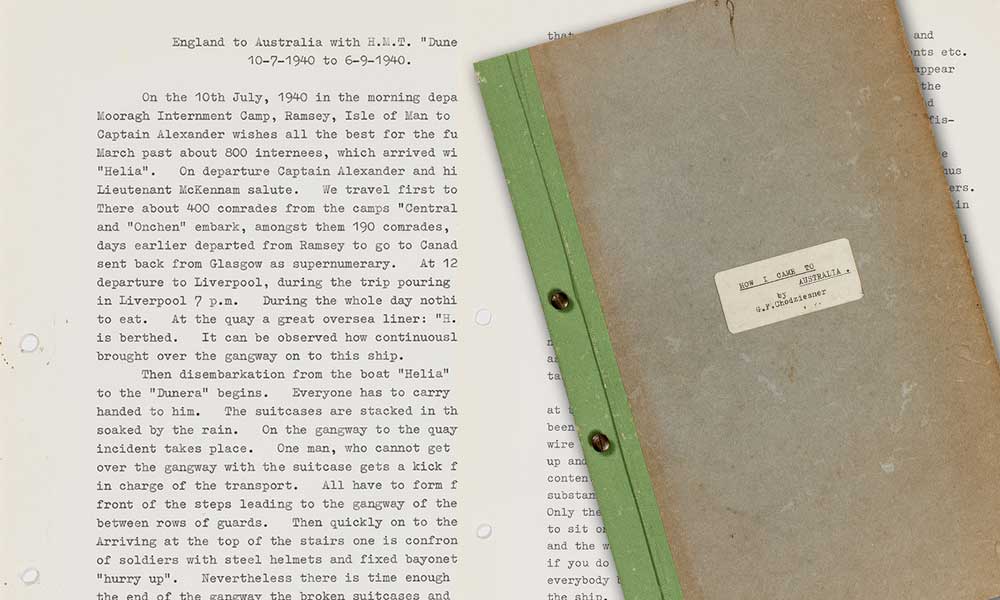

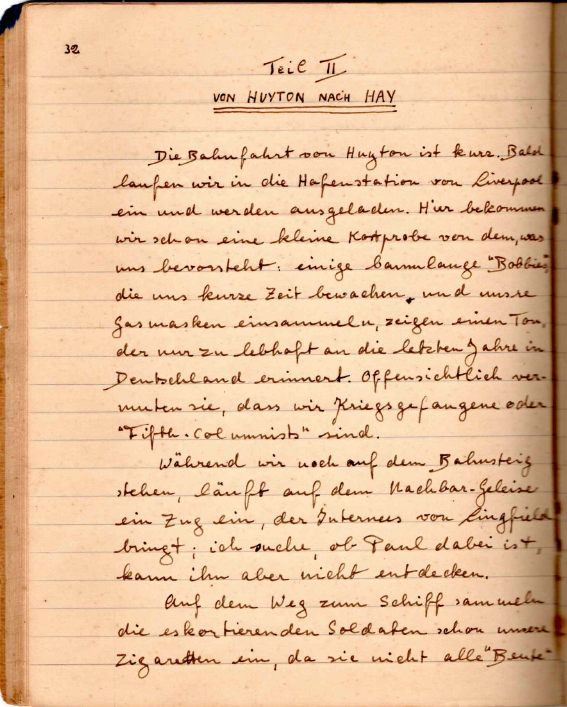

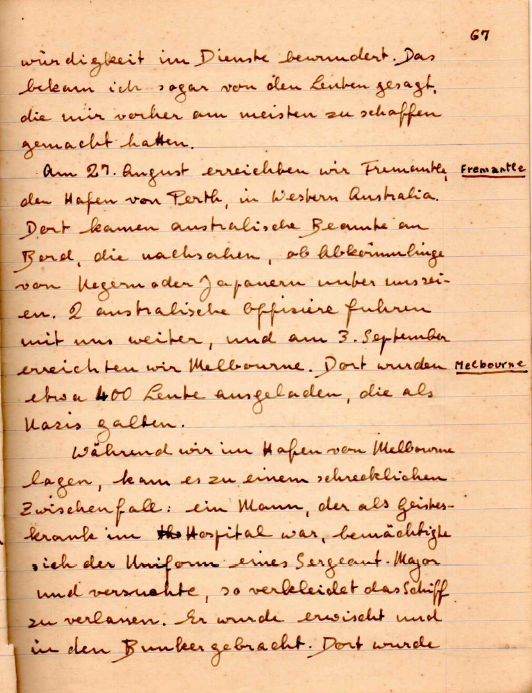

What follows is a rare and unique document, which Günter wrote in his native German while interned in Hay, New South Wales between November and December 1940. In Günter's own words, it "is not meant to be a diary... but instead an attempt to record the memories of this journey that have remained in my mind."

The document is split into two main sections: Part I, Blandford and Huyton and Part II, from Huyton to Hay. This is Part II.

Translator's note:

This is a translation of an original handwritten document. For the sake of readability and consistency, some small changes have been made (ex. incorrect English spelling has been corrected and numbers and dates have been made uniform). The most notable change is that the name of liaison officer, John O'Neill was, in all but one instance, misspelled throughout the entirety of the original diary (O'Neil rather than O'Neill). Otherwise, the translation sticks closely to the original document and all capitalisation, usage of inverted commas, inconsistencies and incorrect information is a true reflection of the original.

The train ride from Huyton is short. We soon arrive at the port station of Liverpool and are unloaded. Here, we are given a brief taste of what’s in store for us: some huge 'Bobbies', who guard us for a short period of time and collect our gas masks, display an attitude that is all too reminiscent of our final years in Germany. They clearly think we are prisoners of war or 'fifth-columnists'.

While we are still standing on the platform, a train stops on the neighbouring tracks, bringing internees from Lingfield; I look to see if Paul is among them, but cannot find him.

On the way to the ship, the soldiers escorting us collect our cigarettes because they do not want to leave all the 'loot' for the ones who will be going with us. We were searched for matches and lighters before even leaving the camp, though we were left with cigarettes.

We are driven out of the train station hall in the friendliest manner by the 'Bobbies', and in front of us in the ship, which will be our 'home' for the next eight and a half weeks: the H.M.T. DUNERA. It doesn't seem very large, which makes some people think there is no way we will be going to Australia on it. One theory is that we will be taken to Canada on the Dunera, sent across the continent by train and put on a ship again in the west. In reality, the Dunera is 11,600 tonnes.

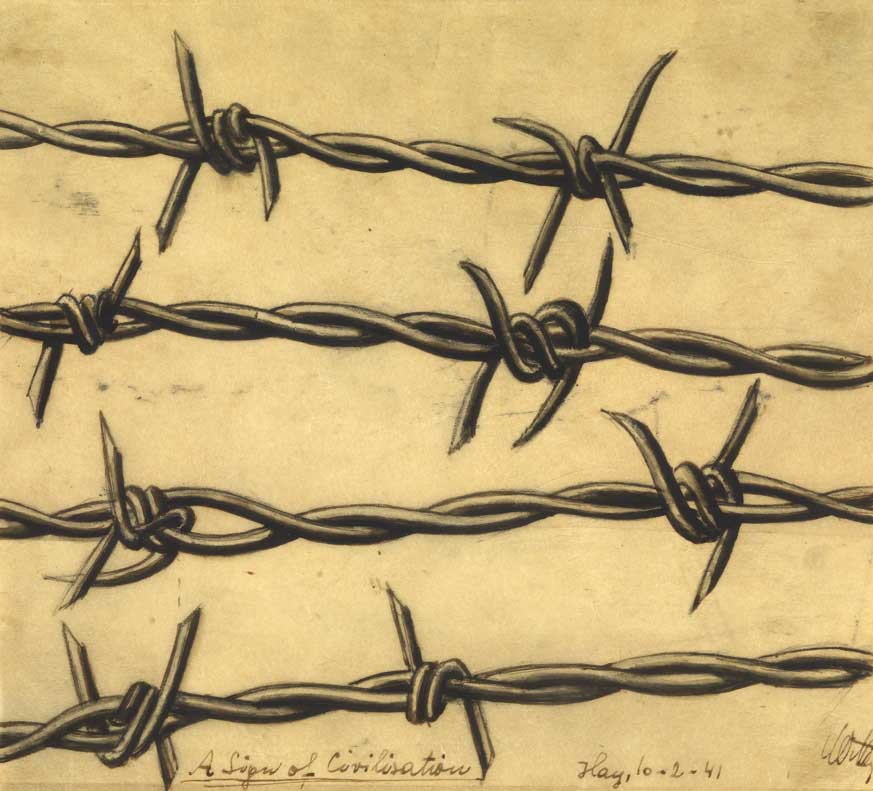

We inch slowly up the deck, on which barbed wire forms a small passage flanked on either side by guards with fixed bayonets. There, all of our luggage was taken and thrown into a chaotic heap. Already at this point, some people were robbed of all of their valuables and, with the occasional blow from a rifle butt, we were driven down into the foreship Upon arriving below, we are immediately searched, though this is completely unsystematic. Some people have all their documents taken from their pockets and - we can hardly believe our eyes - ripped to shreds. Others have money, watches, fountain pens and other valuables taken from them - and receive no receipt in return, of course. Most things are stuck in bags, but some make their way into soldiers’ pockets. I get lucky and am only searched superficially, and nothing is taken from me.

Suddenly, a young man sitting close to me collapses. It turns out that as he was entering the ship, his back was injured by a blow from a rifle butt or bayonet. I am told that he tried to kill himself in Lingfield and since then, he has been very weak. He is taken to the hospital and I have not heard from him since.

When he collapses, I walk over to the tap to get him some water. Suddenly someone calls out to me from the other end of the deck: it's Paul, who came from Lingfield with 400 others. They were told that they were going to another camp and that in a few days they would be able to write from there.

In total, 1100 men from Huyton and 400 from Lingfield are loaded onto the ship and housed in the foreship. There are another 400 people from various camps in Scotland and the Isle of Man as well as 500 survivors of the Arandora Star at the stern. I will talk more about the Arandora Star later. At the start, we did not interact with them at all.

Of the 2500 people, over 2000 were refugees from Nazi Germany!

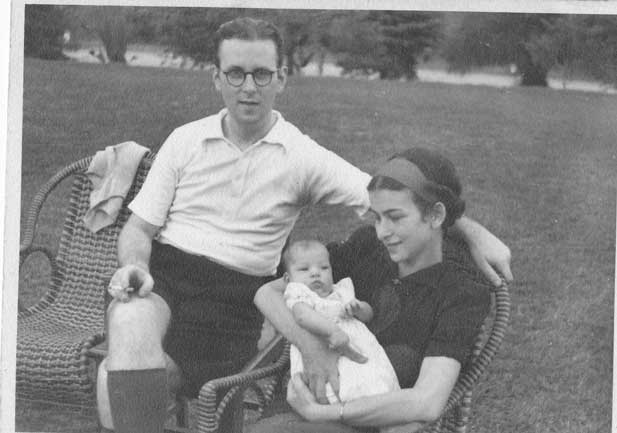

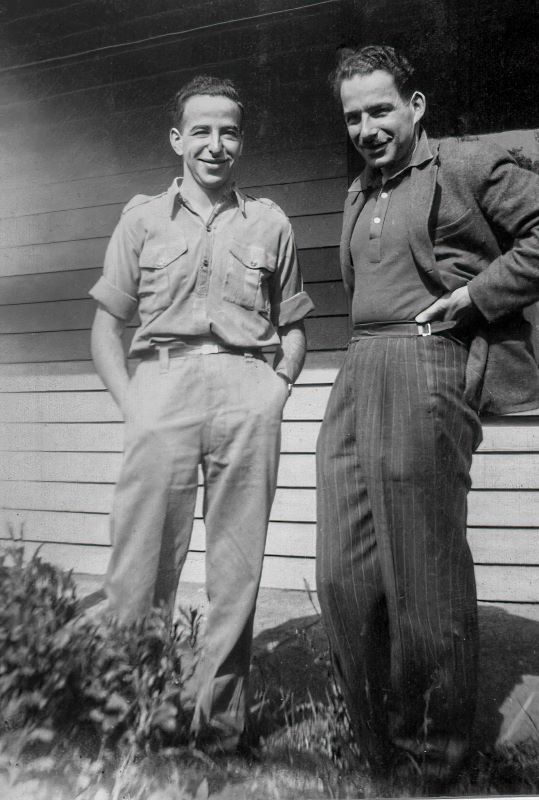

Günter, on the left, and Paul Altmann.

Günter, on the left, and Paul Altmann.

It is impossible to describe what the first night on the ship was like: the 'sanitary' measures necessary as we were not permitted to leave the deck at first; this mass of people, pressed together in far too small a space, in the abysmally poor air; the nervous tension and agitation, the fear of an uncertain 'tomorrow'. For dinner, we were given corned beef and entire loaves of bread, though we were not allowed knives.

We had to spend the first night on the floor, on benches and tables, without blankets or any other mats. On top of that, it became quite cold during the night. The next morning, each man received a hammock and two blankets. However, it turned out that there were not enough hooks for about 1/3 of the group to hang up their hammocks, so they had to spend the entire journey sleeping on the floor.

Late at night, around 3:00 in the morning, on 11 July, we set sail through the North Channel between Scotland and Northern Ireland, through the Irish Sea and into the Atlantic. After leaving the protection of Ireland in the afternoon, the sea becomes rough. The ship zig zags at full speed. Suddenly, we are told we should not be concerned if there is shooting; this is just firing practice. Some people do grow fearful, of course, and work out - correctly - that if we were torpedoed, none of us would probably make it out of the ship alive. Later, there are wild rumours about a torpedo attack carried out by a German U-boot. The torpedo is meant to have grazed our keel without exploding. Suddenly, many people claim to have felt a jolt, while others even say they saw the air bubbles from the torpedo from the window of the latrine. The version the 'Gun Crew' spreads is particularly fantastical. Allegedly, in the moment the torpedo would have made contact, the ship was lifted by a wave, thus escaping destruction. In fact, upon arrival in Sydney, the Commander of our escort, Liet.-Colonel W.P. Scott, told the Sydney Herald the following: we were being escorted by a destroyer alongside a Cunard liner through the Irish Sea when the former suddenly issued a U-boot warning and began circling us and throwing depth charges. Later, we lost sight of both of the other ships, but we continued safely. During all of this, the Italians, who had bad experiences from the Arandora Star, apparently grew frightened and tried to get to the boats on the upper deck. But nothing bad happened.

The next night I am on my way to the latrine when I am stopped and searched in the corridor by a sergeant and three soldiers with fixed bayonets. All I have with me is my watch and they demand it. When I refuse to hand it over myself, I have two bayonets placed on my chest, while the third soldier removes my watch. During this operation, I notice that the soldiers have removed their regiment badges, clearly to make it more difficult to recognise them later on. I am taken, 'on the tip of a bayonet', first to the latrine and then back to the deck, where I am threatened and then released.

That same night, most people grew seasick due to the poor air quality in the overfilled rooms and the agitation, as well as the zig zagging of the ship. Paul and I got off very lightly, only feeling unwell at the sight of the others. I ate again at midday. Most had it worse, and after an entire morning of that wheezing we are all so familiar with, it was dead quiet during the day.

Soon, we settled in a bit. There were around 280 people on our deck, split into 14 tables of 18-22 men each. I was elected table leader of my table. Among ourselves, we table leaders elected a deck leader and the representatives of the various decks (6 in total) negotiated on our behalf with the soldiers, who were responsible for us. We almost never had contact with the ship's command. Our commanding officer was - as I said - Lieut. Colonel W. P. Scott. Our escort consisted of the '26th Company' Q 'Troops', made up of soldiers from the Suffolk, Royal Norfolk and Gloucester regiments, who - we were told by way of explanation of their cruelty and brutality - had fought in France and had narrowly escaped annihilation just before 'Dunkirk'. Judging by these people’s morals that may have been true. There were also soldiers from the A.M.P.C. (Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps), mostly veterans of the World War, who stood out for being unusually brutal and cruel. That seemed particularly peculiar for these people since, until the middle of June, there had been many refugees serving within their ranks, even on the French front. One of the worst people on board in matters brutality and cruelty was a Sergeant Worthington from the A.M.P.C., who was called the 'Lion Hunter' because he would always prowl around, weapon in hand, as if he were on the hunt. In general, it seemed as though the sergeants were the ones in charge on board. There were about 15 of them, and of them I only found two or three to be halfway decent. Later on, when I interacted with them often as part of my role as head of security, there was a young sergeant from the Suffolk Reg., who seemed very nice to me. He was a tall, blonde and blue-eyed boy, whose name I unfortunately did not learn. However, he was also wearing a suspiciously expensive looking watch at the end.

The liaison officer was initially Lieut. Malony, from an Irish regiment. He was removed after just a short time, however, because he was too decent to us. He used to, among other things, share with us the most recent news from the radio, which they didn't want 'up there'. He was replaced by Lieut. O'NEILL, Sergeant and V.C. from the World War. This individual became the embodiment of the entire journey for us. There was certainly no danger of too much decency with him. I will write more about him later.

Not long after the journey began, we observed from the latrine window soldiers beginning to cut open our suitcases with bayonets. Some of the contents were simply thrown into the ocean, in particular documents and books. Other things found their way into soldiers’ pockets. After being suitably sullied by ocean water, some of the underwear was brought to the decks in chaotic bundles, and we were told that since we had complained about the lack of underwear, here it was. Our request to be permitted to open our suitcases ourselves in the presence of soldiers in order to take out the most necessary items was flatly refused. We were told having luggage with us was completely against the rules. In Huyton, we had received a specific concession that permitted us to bring 80 lbs of luggage with us. At first, we refused to even accept the underwear, in protest of the damage to our property. However, later, when it appeared that most of our property had been lost, we decided to at least save those few garments, and return them to their owners, if possible.

In the meantime, they had started taking us up on deck for 20 minutes per day for so called exercise. At all four corners, there were manned machine guns, though they looked like they had not been able to fire for a long time. In the walkways all around, there were guards with fixed bayonets, who hurried us along with blandishments such as 'Getta bloody move on!' and occasional blows from their rifle butts. When O'Neill was in a bad mood, he would grab the arm of an older man, who was not running fast enough for him, and force him to run across the entire deck. One time, a sergeant threw an empty beer bottle at one of our people, who injured his feet on the shards of glass (for hygiene reasons, allegedly, we always had to be barefoot on deck). This incident resulted in sharp protest from our side, and we received formal assurance that the sergeant would be punished. From then on, our treatment on deck was a bit better. That was already about halfway through the journey, though. Before that, there were often incidents in which individuals were suddenly stopped by a guard, who would snatch away the rings or watches that they had carelessly been wearing in a visible location.

In spite of all of these incidents, the 20 minutes on deck were the nicest part of the day - getting to leave the unpleasant lower deck - and only a few people remained below out of fear of the soldiers.

Throughout the entirety of the journey, the food was very inadequate. In the evening, we almost always went to bed hungry, since the rations were insufficient and often so bad that you were simply afraid they might poison you. The margarine was extremely salty, the bread only half-cooked, the meat was sometimes quite spoiled, and the potatoes often completely inedible. All that very much contributed to the fact that, as we sailed through the tropics, even the strongest people suffered from diarrhoea. In Australia, where we were later catered for extremely well, it took most people's bodies around one month to reach a state of equilibrium between the energy they required and what they were able to consume.

We are still in the first weeks of the journey, though. The only activities available to us were playing cards, chess with pieces we made ourselves (from bread crumbs), and some books, which we got from the M.O. and from Jonny, the man from Secret Service. Smoking was strictly prohibited and anyone caught doing so would end up in the bunker. In spite of that, people smoked in the latrines day and night. Because the demand for cigarettes far outstripped the supply, a black market developed, which morphed into something that could only be described as shameful. Our people, who worked in the kitchen acquired cigarettes from the ship's cook, which they sold at a 50% to 100% markup. Unfortunately, there were also people, who stole watches and valuables from their comrades and profited from it.

The first port we docked at - on 24 July - was Freetown, Sierra Leone. The day before, the soldiers were seemingly hoping to get their hands on some valuables and cash in the event of possible shore leave. At any rate, the decks were searched thoroughly. A few days earlier, on 16 July, there had already been a search and they had played a very cruel trick. They told us that we should hand in our watches, etc. in an orderly manner so that the plundering would stop. On top of that, an officer promised that he would keep the things safe and return them to us in Australia. After we had all handed everything in, in a nice orderly fashion, we were told that the bag containing the items had disappeared from the officer’s cabin, where it was being kept, and it could not be found. At any rate, all the soldiers were suddenly walking around with watches and fountain pens.

When the second search happened before we docked in Freetown, they made us go on deck barefoot for the first time, so that we couldn't hide anything in our shoes. During our walk, they rifled through our things, and when we returned, we had been looted.

This led to an incident. One of my friends, Ulrich Kubach, a nice boy of 21, saw a sergeant sticking a fountain pen into his pocket and loudly voiced his disapproval. That resulted in a fight between him and the sergeant, and he requested to see an officer. Instead, he was locked in the bunker. After two days, he returned, but on the third, he was taken back and brought in front of the Commander, who sentenced him to 28 days in the bunker for attempted rebellion (!). In the bunker, he was beaten once at the start with fists and rifle butts. Then, for the first eight days, he did not have much to eat and had no opportunity to wash himself. Later, he was treated quite decently.

As we approached Freetown, we 'clung' to the few portholes we had access to. It was peculiar to suddenly see a headland gliding past, with palms and individual houses resting on columns, behind which a mountain range rose up like a shadow.

In Freetown, we took on food and fuel. There was no fresh water. Because of that, we were put on very strict water rations, which were still not eased after Takoradi (Togo), where we stopped on 27 July: virtually all we had for washing was ocean water.

While in the harbour, we were not allowed on deck and all the portholes had to remain closed. The heat was unbearable, in particular in the washrooms.

On 29 July, we crossed the equator. We got lucky with the weather because the sky was cloudy on those days. But even then, it was terribly hot in the lower decks, and many people suffered from diarrhoea and fevers. We had no clothes to change into, the conditions were extremely unsanitary, and the food was completely inadequate. I only had one day of bad diarrhoea but was not sick otherwise.

At that time, the deck leaders gave me the task of organising and being head of a security service, which had been approved by the military authorities. My tasks were 'traffic control' at mealtimes and during the walks on deck as well as general security, in particular at night. In addition to that, I was responsible for distributing loo paper, which we were always short on. I was of the opinion that we were at the mercy of the military authorities. Because of that, it seemed to me that my most important task was to, to the best of my ability, prevent friction - both among our people as well as with the military authorities. Obviously, this led to much hostility, as I was viewed as one of the soldiers’ servants.

Shortly before Capetown, there was engine trouble, and we could only continue at half speed. Because of that, the rolling of the ocean suddenly became very noticeable and a lot of people were seasick. I actually found the rocking quite fun, under the deck, when the plates slid energetically across the entire table, or on deck, when the reelings on both sides seemed to take turns dipping into the water.

Late in the evening of 7 August, we entered the minefield off Capetown. We had to remain there overnight. The next morning, we entered the port. From the place we docked, we had a splendid view from the latrine window over the bay to the city and Table Mountain, the top of which was shrouded in clouds. Our people spent the entire day standing in queues in front of these two windows in order to at least have seen something on this journey. It was a peculiar sight for us, having come from 'darkened' England, to see the brightly lit city at night.

Of course, the cook smuggled newspapers into the ship, which we virtually devoured. They reported, among other things, that Germany was planning to invade England and that a German 'Raider' was up to no good in the South Atlantic.

Naturally, the soldiers guarding us had shore leave while we were in the port, and just as naturally, upon their return (according to rumours, some did not return at all), they were completely drunk. That meant that, within our ranks, a certain level of nervousness prevailed because when the soldiers were drunk, there were often 'incidents'. Capetown was no exception. On the second day, two boys of around 17 crossed the foredeck without an escort - which was of course against the rules - and were stopped by a guard and locked in the bunker. Then Mr O'Neill returned from shore leave completely drunk and went to have a look at the 'criminals'. I heard what happened during this inspection from Ulli Kubach, who witnessed it from his bunker. The boys had been chained back-to-back. O'Neill began savagely berating them. He had them untied and tried to provoke them, by repeatedly yelling in German: 'Your father is a pig, you are a pig'. Because the boys were afraid to defend themselves, of course, he hit them. He hit one of the boys in the face, and the latter fell to the floor. Then O'Neill had them tied up again. They were only freed in the evening when a ship officer intervened.

We left Capetown on the evening of 9 August, with one final look at Table Mountain. As soon as we left the protection of the cape, the ocean was rough, and I spent the night helping people to the washroom.

We were now on the longest leg of our journey - from Capetown to Freemantle (Western Australia). To me, that was the nicest stretch. We felt as though the worst was behind us. We believed that our ever-nearing arrival in Australia meant the English were thinking they should not make too poor an impression on us.

During this leg of the journey, I had the opportunity to more frequently observe O'Neill from close proximity. One time I had to speak with him and asked a guard: 'Do you know where Mr. O'Neill is?' Whereupon he responded to me: 'He is down there - at the stores - filling beer in. I wonder what he is f-- good for' [Note: This section appears in English in the original diary, hence the non-standard phrasing]. That's what the soldiers thought of their officer.

Every morning, O'Neill listened to our speakers’ report. He generally made them wait for half an hour first and then complained to them that we were not moving fast enough during our walks on deck, etc. Usually, he was already drunk during the morning report. If we wanted to complain about something, we were told that everything is happening in accordance with the orders from the War Office. The Commander Lieut-Colonel Scott repeatedly refused to accept any memoranda from us and threatened to lock up our speakers if they tried it again. During the report one day, O'Neill became furious when the rabbi Dr. Ehrentreu, a dignified, older man, contradicted him and said he wanted to grab him by the beard and hang him from the highest mast!

There was ongoing friction with O'Neill over visits to the doctor. The hospital was located at the rear of the ship. The people, who wanted to go to the doctor, were escorted to the back in groups of 15 to 30 men. O'Neill always wanted to limit the number of people, while the Medical Officer wanted to see everyone, who was feeling unwell. The whole thing was made more difficult by the fact that there were always quite a few people, who used a visit to hospital as an excuse to go on deck again. I was then the one who had to pay for that.

I never went to sleep before 2:00 - 3:00 each night because some of our people would always get up to no good late in the evening. Otherwise, it was pretty calm, apart from occasional inspections by the 'Lion Hunter' or when someone would collapse in the corridor with diarrhoea and a high fever, and I would have to alert the guard and send the man to hospital.

As an aside, the sick were actually cared for by doctors from our own ranks.

There was one very thrilling night. In the middle of the Indian Ocean, there was engine trouble and for several hours that night, we were at the mercy of quite rough waves. Said waves, in their rocking, broke through the wooden cladding of the kitchen window, which meant that, firstly, water got in from the outside, and secondly, the light inside flooded out; the former was undesirable because the water made it to our decks, and the latter because there was supposedly a German Raider nearby and it was too cold to swim. So Felix Solmitz, our head of cleaning, and I set about darkening all the lights and clearing away all the water, while the ship’s carpenter repaired the cladding. But the waves’ game continued and we had to darken the lights and clear away the water three more times, and only once the ship continued on its path were we able to lay down and sleep.

Felix Solmitz really did an excellent job when it came to keeping things clean. He worked tirelessly from early morning until late at night. His contributions were probably the decisive factor in keeping us from degenerating into filth over the course of the voyage.

At this point, I would like to share a poem, which paints a vivid picture of the atmosphere on the journey. Poet unknown.

THE DUNERA SONG

(Melody: 'Unrasiert und fern der Heimat')

- Unshaven on board the 'Dunera', and Australia is our destination. Our suitcases have been disgorged, and O'Neill is wearing our shirts.

- Sharp weapons and dull teeth, there the English soldier stands. The brave barbed wire ensures no one leans on him.

- We run during the walks, the soldier yells out: 'Hurry up!' To go buy things in Capetown, they take our cash from us.

- Thank you, dear cooks, thank you for dinner. If we had eaten it, we would have been dead long ago.

- And in our canteen, you can buy chocolate. But the water of the canteen sprays up to your a-.

- So that you can live in Australia, they're turning you into a kangaroo; teaching you to take big jumps, you also have an empty pouch/bag.

- Friend, why are you looking into the waves, do you see a shark? You do not need to bother, the shark is already on board.

- On the bread, there is margarine, mutton and white beans. O latrine, o latrine, have you heard the latest yet?

- Smells spread through the washroom, tea flows between the tables, pots roll through the kitchen, but the sea rests in peace!

This song has humorous aspects, but in spite of all the evenings of light entertainment, variety shows and singing (a men's choir led by Mr Prof Meyer from Oberammergau and Tenor Liffmann from Düsseldorf), people’s morale grew worse and worse by the day. No wonder, though, if you really try to imagine the conditions. Many of the people had been sent on this journey contrary to explicit promises made. All of us suffered due to the overcrowding because we spent night and day on the decks, which were 30% too full, without proper nutrition, with poor air and mediocre lighting, without clothing to change into and on top of that, we were constantly afraid of being abused by drunken soldiers. Perhaps all of this would have been easy to bear if there had been some sense of community among all of these people, but that only existed in isolated cases. Not even the danger we constantly faced, nor the collective awareness of the injustice that had happened to us could bring us together such that we would be spared at least the friction of everyday life.

For example, mealtimes constantly threated to become a battle of everyone against each other. Our people were so hungry that they fought over almost every piece of bread and every apple (apples were our only fruit, and we only got one per week). How it worked was that once the announcement was made, two men from each table would race like mad to the galley, be served and then they had to return. The way there and back led through a small passage which, because it passed a ventilation shaft, was always very full. That certainly did not make carrying out this job any easier.

In the kitchen, they had to pay close attention to make sure one table did not get food twice. To that end, we issued little tablets that were certified with two signatures. There were sometimes 'seconds', which were fiercely fought over.

On Sundays, we did not get a walk on deck, because the soldiers had that day off!! There was, however, a Catholic service on deck a few times, which was surprisingly well attended.

My role during this time was not simple. It started with breakfast at 7:00 in the morning, followed by escorting the sick, then the walk, then escorting the sick again, then lunch. After that meal, I usually had a two-hour rest. I could spend that with the labourers on deck but I only rarely did so because there was usually a big fight about who was a labourer and who was not. Really, it included the people, who worked in the kitchen, bakery, laundry and cleaning.

For me, the worst thing was actually that people were constantly testing my patience with countless questions, which of course often concerned my authority. Sometimes it took a lot of self-control to not become impatient. Only a handful of times did I really yell at someone, and twice I had to send people off by force. At the end of the journey, I had the satisfaction of having a number of people say to me that they had admired my persistent calmness and courtesy in my role. I even heard that from the people, who had caused me the most trouble.

On 27 August, we reached Fremantle, Perth's port in Western Australia. There, an Australian official came on board to see if there were any descendants of blacks or Japanese in our midst. Two Australian officers continued on with us, and on 3 September we reached Melbourne. There, 400 people, who were said to be Nazis, were unloaded.

While we were in Melbourne’s port, a terrible incident occurred: a man, who was in hospital as he was mentally ill, took possession of a Sergeant-Major’s uniform and tried to leave the ship dressed like that. He was caught and brought to the bunker. There, he was beaten half dead by four sergeants with batons and left lying in his own blood. At night, three senior officers went to look at him and when they left, I saw one was carrying a blood-soaked rag. The man was not taken to hospital until the next day.

Over the course of the journey, there were three deaths. A man from the back of the ship jumped overboard during a walk on deck and could not be found. It was said he lost his mind upon learning that all his papers for America had been destroyed. One man died of some disease in hospital, and a third suffered a heart attack due to a fight.

Shortly before the end of the journey, I had the opportunity to speak with a man from the Arandora Star. The following is based on what he told me and other things I heard about it:

The Arandora Star, a passenger steamer weighing around 21000 tonnes (?), departed England on 2 July with 1500 civilian internees as well as German and Italian prisoners of war on board. The people were accommodated well in the cabins and were treated decently. On the first evening, they were permitted to purchase alcoholic drinks. The next morning, a few hundred miles west of Ireland, the ship was torpedoed and sank within 20 minutes. The Italians stormed the boat deck and when the English soldiers tried to stop them, they were disarmed. Of course, everyone was panicking. There was a terrible pushing and shoving in some of the stairwells because people were trying to bring their suitcases on deck.

By that time, the boats had been lowered and some of the prisoners had gotten into them. Others tried to jump into them from above and in so doing broke their necks. Soldiers, who were unwilling to leave their weapons behind, threw them into the boats from above, thus damaging them. Fights broke out in the boats, in particular between the Italians and the English soldiers. Space in the boats was completely insufficient, which was made worse by the fact that some boats had been damaged.

Around 500 prisoners and the same number of Englishmen were rescued. The prisoners were brought to Cardiff and left there in an empty factory building for a week, with barely the most necessary clothing. There, they had the pleasure of reading horror stories in the English newspapers about their poor behaviour and the 'heroism' of the English soldiers. Barely eight days later, they boarded the Dunera.

During the first half of the journey, we were strictly forbidden from having razor blades. Very quickly, of course, we began to look like pirates or emigrants from a Polish ghetto, in particular with our torn clothing. An unpleasant side effect of this was that many people got tinea barba, a quite dreadful skin disease. Luckily, they were sent to hospital right away, so at least there was no widespread epidemic.

Then, as we got closer to Australia, Mr O'Neill began to feel a bit embarrassed at the thought of handing us over to the Australians as full-bearded Struwelpeters, and a compulsory haircut and shave were arranged. Our hair was cut on deck by Italian barbers, and we had to shave using instruments the soldiers had stolen from our suitcases.

On the way from Melbourne to Sydney, we stuck close to land because the German Raider was allegedly nearby. (14 days later it came out that there had been mines in the Bass Strait.) Our passage through the strait, which is feared due to its storms, was very peaceful and on 6 September at 11:45, we passed under the Sydney Bridge and docked. Our sea voyage halfway around the world, through three oceans and past three continents, was over after 59 days. We were unloaded immediately and boarded the trains that were standing by.

In boarding the train, this chapter comes to a close. I really felt like I had escaped hell. We were sitting in proper carriages with comfortable seats; the guards, Australian diggers from the last war, were polite and friendly.

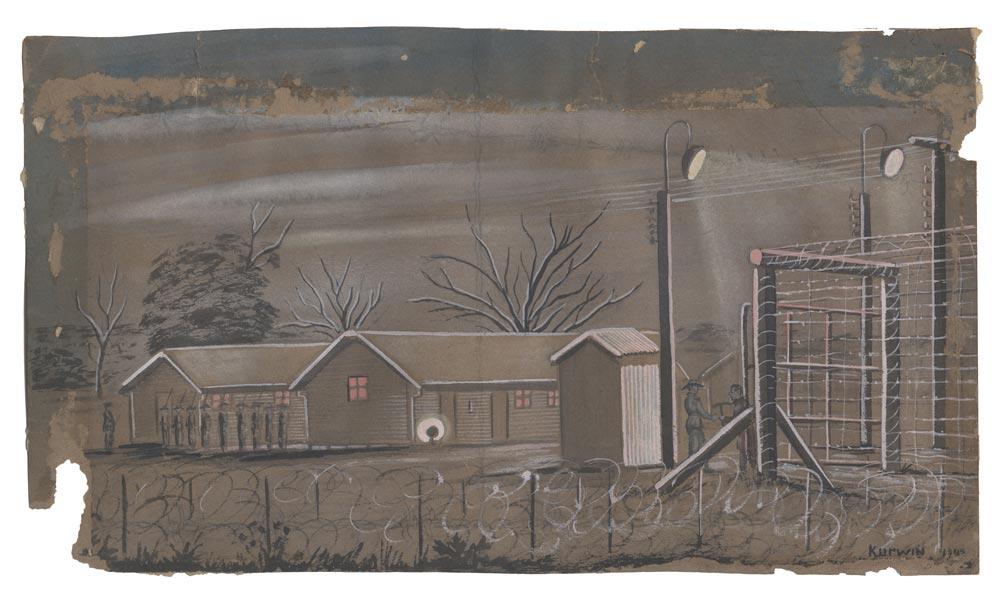

From the train station at the harbour, we travelled in an arc around Sydney and after one last look at the Dunera we headed west, to our new 'home'. We arrived in Hay, NSW the next morning; we marched between rows of the local inhabitants, who were quiet but not unfriendly, to the 'camp', the place we would be living for - how long?? They say you forget unpleasant things quickly, but I believe it will be a long time before this journey, these visions of overfilled rooms, undernourished, half-sick people in ragged clothes and drunken soldiers, disappear from my memory.

There are many other details that I could share about the brutality of the soldiers, the dishonourable conduct of the officers, the suffering of all of our people, and the unbelievable cruelty of a few individuals, who tried to capitalise on the distress of their comrades. This is not meant to be a diary, though; instead it is an attempt to record the memories of this journey that have remained in my mind.

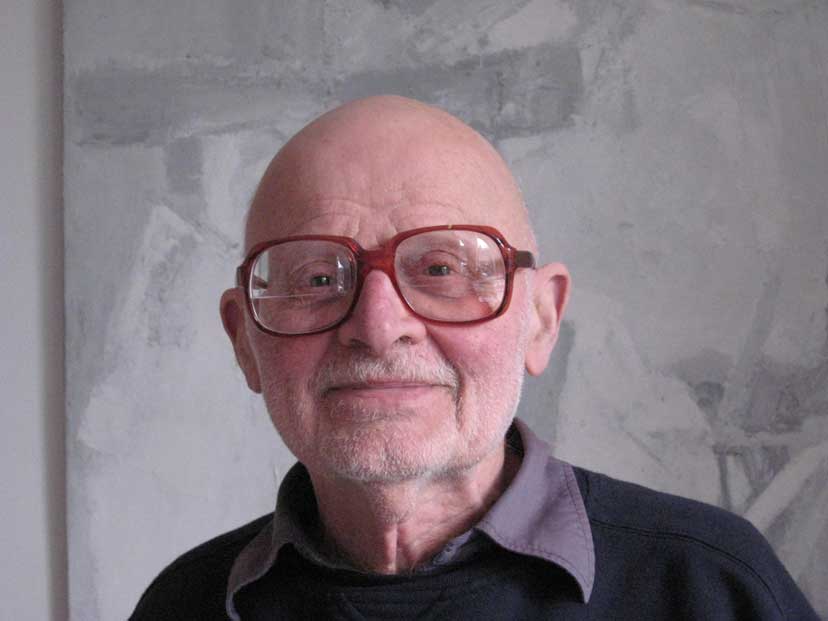

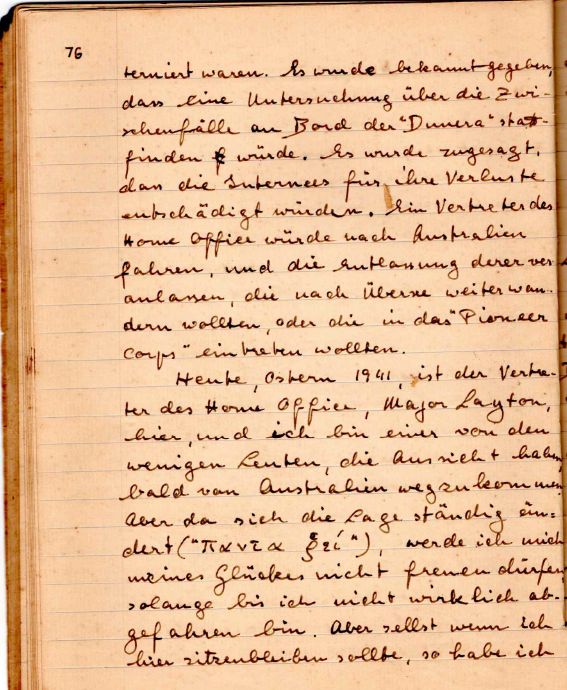

Günter on his wedding day.

Günter on his wedding day.

AFTERWARD

Once the danger of a German invasion had faded, people turned their focus to the mistakes that had been made. The 'Home Secretary', Sir John Anderson, who was accused of serious negligence in the preparation of air raid shelters, left his role. His successor, Mr Herbert Morrison, also turned his focus to the issue. Had the internment of almost all 'refugees' been justified or not? He came to the famous conclusion: 'Mistakes have been made!'

In January 1941, details of our treatment on the Dunera suddenly came to light. Questions were asked in parliament. It was revealed that the Dunera was intended to carry 2000 passengers, but that 2500 had been interned aboard it. An enquiry into the incidents aboard the Dunera was announced. Internees were promised that they would be compensated for their losses. A representative of the Home Office would travel to Australia and arrange for the release of anyone, who wanted to migrate elsewhere overseas or enter the 'Pioneer Corps'.

Today, Easter 1941, the representative of the Home Office, Major Layton, is here, and I am one of the few people, who may be able to leave Australia soon. But because the situation is constantly changing ("[Note: this section of the diary contains a short phrase of what may be Greek - see image below]"), I will not celebrate my luck until I have actually departed. But even if I do remain here, I am comforted in the knowledge that I am just a 'MISTAKE'!

'Court Martial of Guards'

(Sydney Morning Herald, May 15, 1941)

Alleged Ill/treatment of Internees.

London, May 14. (AAP)

[Note: what follows is copied directly from an article run in the Sydney Morning Herald on this date.]

In the result of the report of the Court of Inquiry which investigated allegations of Ill-treatment to German and Italian internees on the liner Dunera, which took them to Australia, the Secretary for War, Capt. H.D.R. Margesson, stated that he had ordered the trial by court martial of the commanding officer of the military personnel on board, and the regimental sergeant-major and a sergeant.

The Dunera arrived in Sydney from England last September with the first large batch of Germans and Italians for internment in Australia. They were guarded on the voyage by British soldiers. It was announced in the House of Commons in February that investigations were being made into allegations about the conduct of the guards during the voyage.

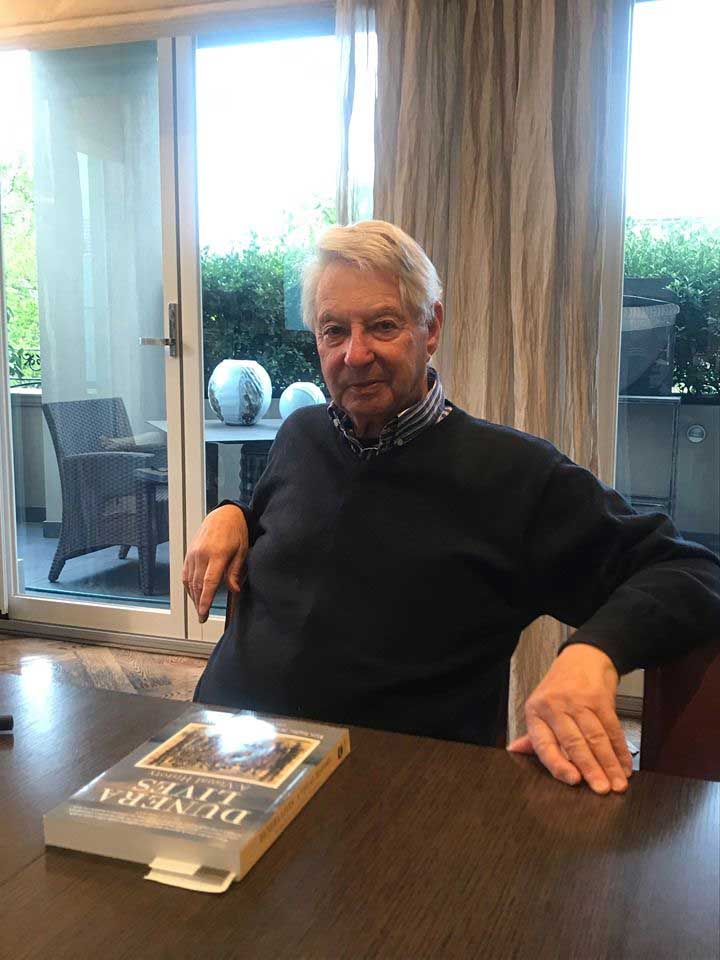

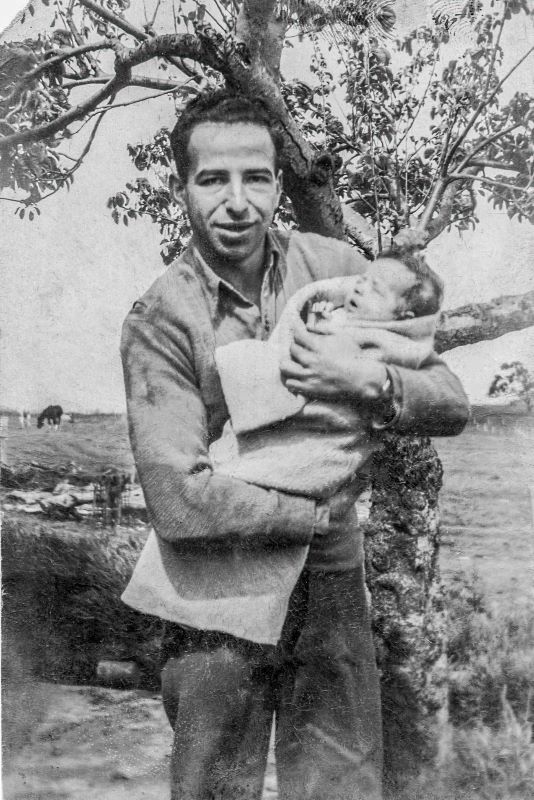

Günter with his daughter, Margaret, not long after leaving Australia.

Günter with his daughter, Margaret, not long after leaving Australia.

All images © Margaret Riederer

Author: Translated by: Kate Garrett