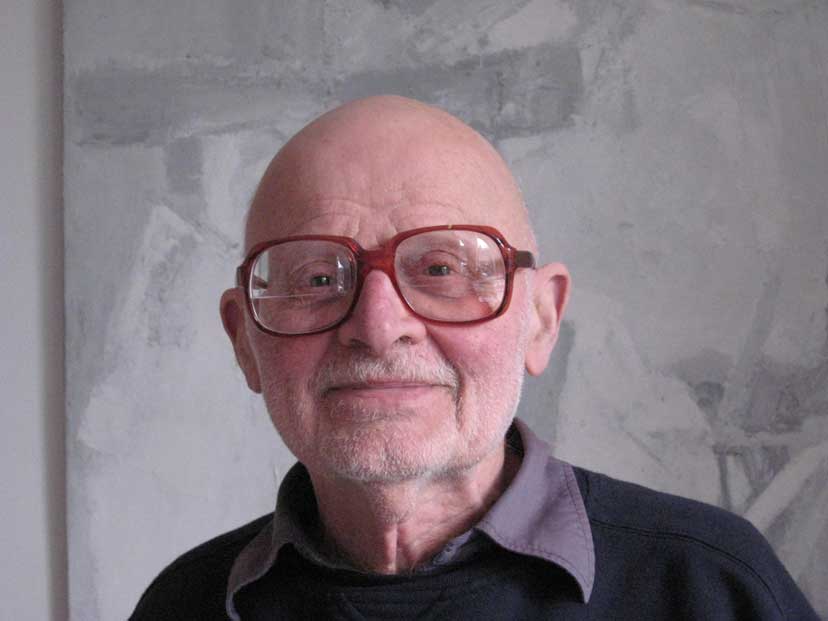

For those with a keen interest in economics, the name Gerry Gutman may be familiar. Like his close friend and fellow Dunera boy, Fred Gruen, Gutman made a name for himself as an economist and proponent of labour market reform and authored the book, Retreat of the Dodo, in which he bemoaned the rigidities of Australian institutions. Gerry Gutman died in 1992. Dasia Black, psychologist, author, lecturer in child development and the psychology of racism, and Gerry's wife at the time of his death, shared her memories of his story and their life together.

Born in Munich on 28 September 1922, Gerry Gutman was still a child when his parents, Otto and Helene Gutman, first began considering sending him to England. This was precipitated primarily by the Nazi Bücherverbrennungen, which aimed to rid society of ‘un-German spirit’ via the burning of Jewish, "Leftist" and democratic literature. While these occurred throughout the 1930s, they reached their peak in mid-1933 when, on 10 May, the German Student Union burned upwards of 25,000 books in Berlin's Bebelplatz. Of course, sending young Gerry away was not a decision lightly made, nor was it easy to act on at the time.

Fortunately, his parents were not without contacts outside of Germany. His mother Helene, originally from St. Gallen in Switzerland, had, as a young girl, been cared for by an English governess. By the early 1930s, Helene, now an adult with children of her own, was able to make contact with her former governess, who had long since returned to Britain. The governess agreed to take Gerry in.

By this time, several years had passed: Gerry left for England in 1936. It is unclear how Gerry's parents were able to secure him a spot on this journey, though it was not one of the official Kindertransports, which didn’t begin until December 1938, less than a year before the outbreak of the Second World War. Dasia recalls Gerry sharing his memory of their tearful goodbyes: his father attempted to remain stoic while his mother wept, but Gerry, the independent young boy that he was, couldn't wait to ‘get away from all these old people trying to hem him in’. He didn’t know that he wouldn’t see his parents for 30 years.

Gerry's immediate family would survive the war, albeit scattered: prior to Gerry's own departure to England, his older brother Heinz (later Harvey), who suffered from asthma, had gone to stay with his mother's family in Switzerland in the hopes that the dry, unpolluted air would be helpful to his ailments – this may have been the reason that it was only Gerry, rather than both children, who ultimately ended up in England. Gerry's mother later joined her elder son in Switzerland. Gerry's father, Otto, managed to leave Germany for England and later the United States, where he was living at the end of the war.

The years spent in England were not an unhappy time for Gerry, by then a teenager. The governess' brother took an interest in him and his education, and he was enrolled at a good school, where he was able to learn English and make friends. There he learned all the verses of Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which he loved to recite later in life. It is unclear whether Gerry and his father met up during the time they were both in England, but their relative proximity meant Otto was aware of his son's fate when the latter was interned and deported to Australia – a true reflection of the arbitrary way in which the men who would go on to become the ‘Dunera boys’ were detained. Gerry, still of school age at just 17, was interned and deported aboard the Dunera. His father remained behind.

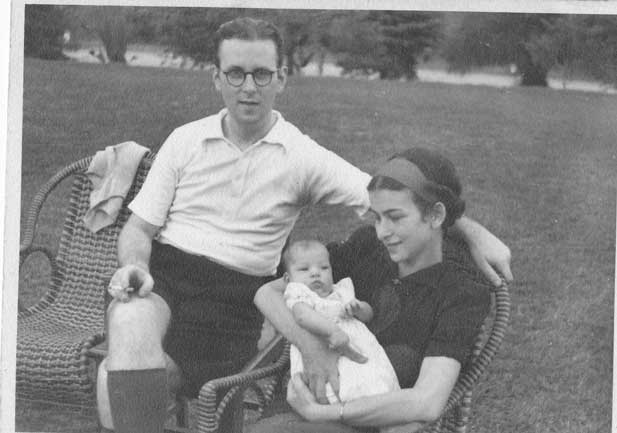

Gerry in 1943; photo taken by fellow internee and photographer Helmut Newton.

Gerry in 1943; photo taken by fellow internee and photographer Helmut Newton.

Dasia and Gerry met in May of 1980, and it was a full year before she learned that he had come to Australia aboard the Dunera: ‘That tells you everything [you need to know] about his feelings about it’, she says. And when she did finally find out, it was not because Gerry shared this information willingly. She recalls a mutual friend saying to her: ‘You know Gerry is a Dunera boy, right?’ Though Dasia wasn't fully aware of the specifics of the Dunera voyage, as part of the migrant community at the time she had a general understanding of the events: ‘we were dealing too much with the Holocaust to not know about it’.

Born Ester Hadasa, Dasia was just three years old when the Nazis marched into her hometown of Zbaraz in Poland. For the next year, she and her parents lived in Zbaraz ghetto, one of the many that were established around Poland during this time to separate and confine the Jewish populations. Living conditions were miserable, and the ghetto populations lived in constant fear of deportation to a concentration or death camp. Out of a pre-war Jewish population of 3000, 70 survived.

Fearing the liquidation of the ghetto they lived in, Dasia's parents were able to smuggle her out to live with a Polish woman named Sabina, where she pretended to be a young Christian girl called 'Stasia'. Both her parents were murdered. When the war ended, Sabina was able to make contact with Dasia's paternal aunt, who together with her husband adopted Dasia. In 1951, just over 10 years after the Dunera docked on Australia's shores, Dasia arrived in Sydney with her adoptive parents.

Even after Dasia found out about Gerry’s Dunera past, he did not speak about it. It was a part of his life that was painful and denigrating, and he preferred not to dwell on it. The only thing he shared with Dasia about the voyage is the moment when he stumbled and his glasses fell from his nose, only to be crushed maliciously under the boot of a British guard. He couldn't see much for the rest of the trip. Similar to many of his fellow survivors and those who endure dehumanising experiences, Dasia believes Gerry likely felt a deep sense of shame about the events he experienced.

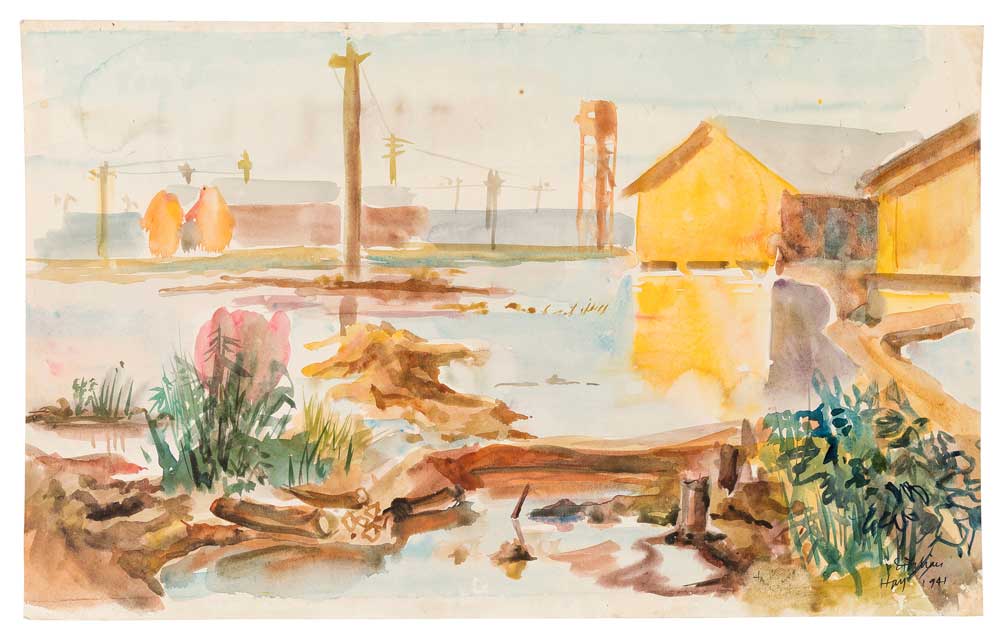

In common with many of the other internees, Gerry was finally able to leave the camp in January 1942 by volunteering for military service. Beyond just the appeal of leaving internment, for many of the young men whose lives had been upended by the war, it made sense: ‘they wanted to fight Hitler, those kids’, says Dasia. Gerry and the other men of the 8th Employment Company didn’t serve overseas, but rather were put to work in Australia labouring for the war effort. Though Dasia says he seemed to have spent most of the war loading cargo onto trucks, this path also led to Gerry finding a permanent home in Australia.

Dasia describes Gerry and his friends at that time as idealistic: ‘they wanted to build a new world, a free and fair world’. After the end of his military service, Gerry received a scholarship to study economics at the University of Melbourne, where he joined the labour movement and surrounded himself with other young people who would go on to shape Australia's cultural life: the future film director Tim Burstall, the painter Arthur Boyd, and the future director of Melbourne University Press, Peter Ryan, to name a few.

Gerry became close with many of these men, and while still living in Melbourne, he put his degree in economics to use, helping his friend Arthur Boyd – at that time still a young and unknown artist – with his taxes. For his services Boyd offered to pay in paintings, which Gerry refused: ‘that won't pay my rent’. Gerry's friend and fellow Dunera internee Peter Herbst, Dasia remembers with a chuckle, had more foresight in that regard: he actively collected Boyd's work early on, and she recalls visiting his home and seeing it so full of Boyd's work that ‘[Herbst] had them outside the house, in the rain, under the eaves’.

On graduation, Gerry was offered a job, with a decent salary, at a firm in Melbourne, but he turned this down. He was determined to go to Canberra and build the new world he had dreamt of when he was still an internee. In 1947, he got a job working in the Bureau of Agricultural Economics, where he eventually reached the position of deputy director. Later, Gerry spent a year pursuing further study overseas at Oxford, returning to the country that had interned and deported him during the war. At Oxford, his supervisor was the esteemed English economist Sir Thomas Balogh, who would later describe Gerry as ‘an Australian larrikin with an original Teutonic mind’. Dasia believes this was most fitting.

One of the formative experiences of Gerry's life was the time he spent working in Karachi in Pakistan as part of the Harvard Development Project. He lived there for five years, working on a project that involved diverting the Indus River to aid in irrigation. His life at this time paralleled that of his brother, in many ways. Harvey had ended up in the United States, where he found a job with the State Department and spent many years working on similar projects in Africa.

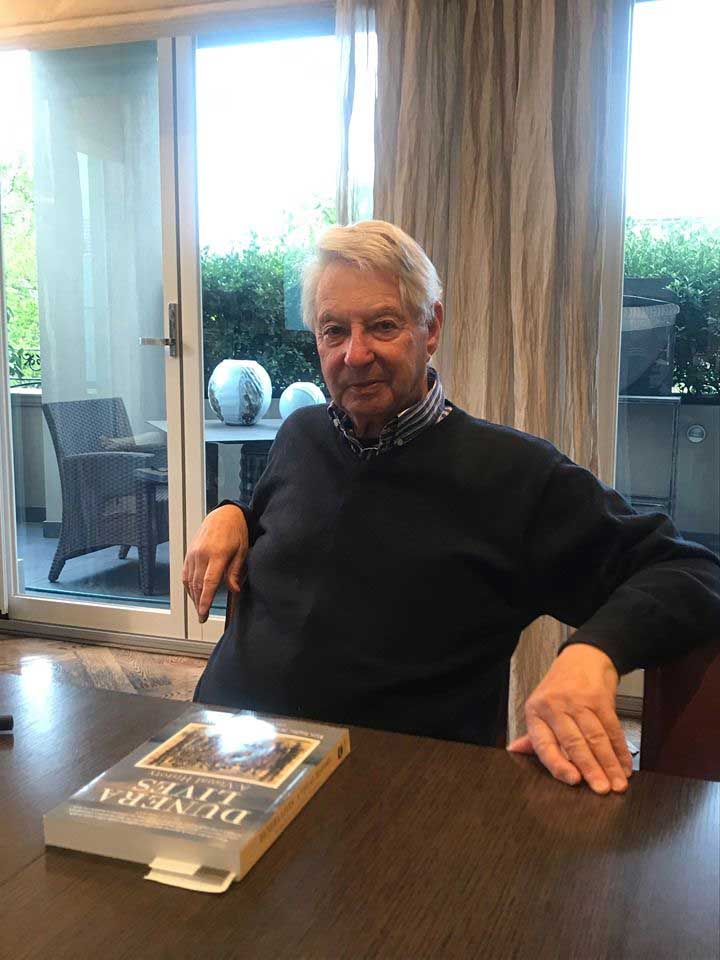

Gerry and Dasia at a wedding reception in 1990.

Gerry and Dasia at a wedding reception in 1990.

Dasia and Gerry met via a mutual friend, who Gerry knew through his role as First Assistant Secretary of the Department of Territories. Though educated herself – Dasia was working on completing her PhD, on the construct of empathy in therapeutic and educational contexts, when they met in May of 1980 – she says Gerry ‘broadened her horizons’ in many ways. One of those was artistically. Throughout his life, Gerry possessed a keen interest in art. As a young boy, living in Munich with its great art museums, he would save his pocket money to buy Rembrandt prints and later he developed an interest in Gandhara art – Buddhist sculptures with a Hellenistic influence – which he first became acquainted with in Pakistan. Dasia herself still has some of the pieces, though the bulk of the collection is now proudly displayed in the home of Gerry’s daughter, Tara, in Canberra.

She has many fond memories of their years together and, above all, recalls his thirst for adventure – a quality she says she has taken on, in some ways, since his death. ‘[Gerry] did not want the straight and narrow’, recalls Dasia. It wasn't until they'd lost the trail on a bushwalk or followed a side street off into the bowels of an unknown Japanese city that Gerry felt the adventure was truly beginning: ‘as soon as [we] got lost, Gerry was in his element’.

Gerry Gutman died on 16 January 1992. He was 69. The young man who set out for Canberra adamant that he wanted to make the world a better place, had championed labour market reform, spearheaded an enquiry into gold taxation at the request of Paul Keating during his time as treasurer, and dedicated decades of his life to the service of his adopted country. When Gerry died, Prime Minister Keating wrote to Dasia: ‘I learned of the death of your husband, Gerry, with shock and regret. Over many years, I had come to value his good sense and intellectual courage… In and out of the public service, Gerry was always a public servant of this country, and one whose wisdom we will miss.’

All photos © Dasia Black

Author: Kate Garrett