Not every internee who came by boat to Australia during the Second World War was male – much less an adult. While the passengers on the Dunera were all men, another ship, the Queen Mary, brought another group of passengers to Australian shores: families. And they were not coming from Great Britain, but from British Malaya, which today makes up parts of the Malay Peninsula and Singapore. Some 266 men, women and children, considered a threat to the Straits Settlements, were rounded up and sent to Australia. Ruth Simon was one of those children.

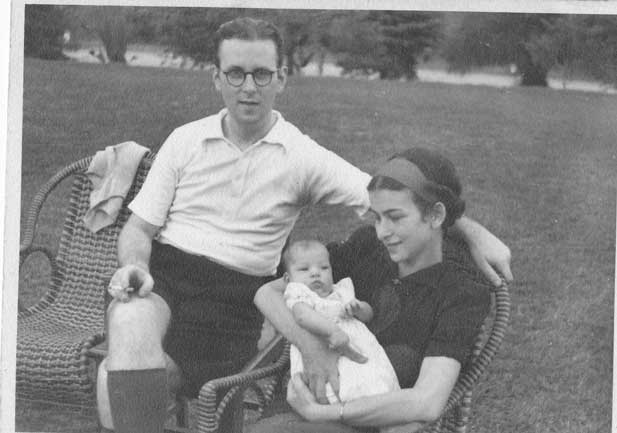

Ruth with her parents in British Malaya.

Ruth with her parents in British Malaya.

Ruth's mother, Johanna Bianchi, was from Vienna; her father, Otto Gottlieb, from Tyrol. Her mother was Catholic, her father Jewish. Otto's was the first Jewish family in their small village of Wörgl, and Ruth tells us that, by and large, his memories of this town were positive. For the most part, people there were kind to him, and during his school years, Otto, her father – the only Jewish student in his school – won a scholarship to travel from his hometown to Rome for an audience with the Pope. Ruth chuckles at the irony. After the war, three of Otto's former classmates made the effort to reach out to him in Australia, and they kept up correspondence for many years.

Johanna and Otto met in their teens through mutual friends, after Otto moved to Vienna to pursue his studies. They married several years later, following Otto's return from a stint in Italy, where he worked as a civil engineer. Their marriage coincided with the introduction of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 – right after Johanna had converted to Judaism. ‘She always said her timing was never very good,’ says Ruth with a wry smile.

Not long after they married, Otto was captured and interned in Dachau – for ten days – before Johanna's brother was able to pay for his release. As a Lutheran, this show of support for his Jewish brother-in-law was brave, but certainly not without risk. Ruth says her mother was shattered by her father's imprisonment. She would later tell Ruth that those ten days took such a toll on Otto that she barely recognised her husband when she saw him after his release. Her father never spoke about what happened in Dachau, but the experience stayed with him. Otto would not return to Europe, even to visit, until the 1970s, and according to Ruth he was not interested in the memorialisation of the camps. These were the locations where his family members were murdered, and Ruth recalls his saying he couldn't understand why people would want to go back and look at Dachau. But in spite of this, and though Ruth's father was open with her about what had happened in his country of birth, she does not remember any bitterness.

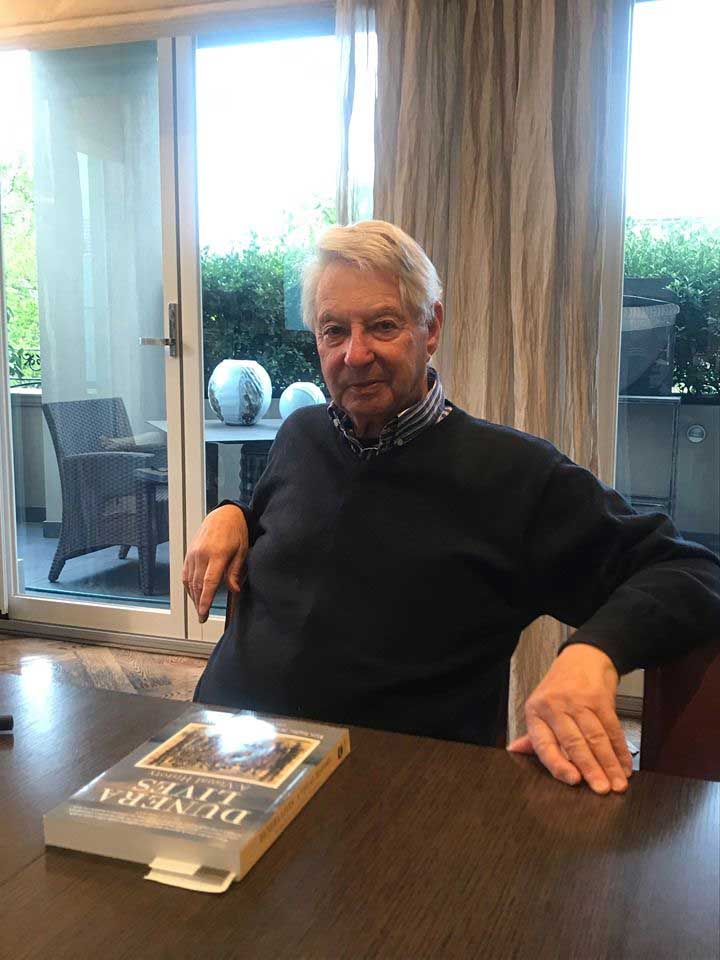

Ruth as a young child, before leaving Europe.

Ruth as a young child, before leaving Europe.

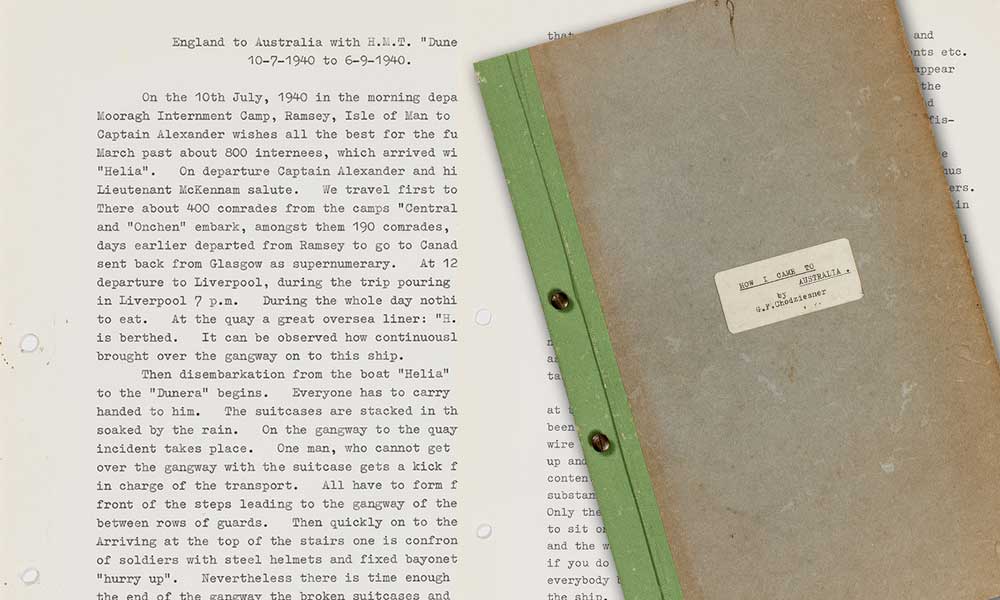

Ruth was born in the small town of Novi Ligure, Italy, in 1936. Her family did not remain there long. The rise of National Socialism and anti-Semitism across Europe meant her parents soon began searching for ways to leave the continent. Her family had cast a wide net, looking for safe harbours as far abroad as South America and Asia. They were accepted somewhere in South America; Ruth does not recall where exactly. There was even talk of going to Shanghai, which at that time was an open city that required no passport or visa for emigrants, making it a beacon of hope for Jewish refugees as one country after the next shut its borders. Although Johanna had converted to Judaism, in the eyes of the Nazis, she was not considered Jewish: when the time came, her Jewish husband boarded a ship and headed east alone.

The ship was most likely heading to Shanghai, though Ruth is no longer certain. When it docked for a time in Singapore, a representative from a British mining company came on board looking for an accountant, a baker and, most importantly for Otto, a civil engineer. Otto disembarked and headed off to his new employment, deep in the jungle far outside Singapore. Ruth and Johanna boarded a ship and followed soon after. Ruth once asked her mother if she, and Otto before her, were afraid to leave Europe. Did she ever consider not following her husband to Malaya? Johanna responded, ‘Oh, no, I loved to travel.’ Ruth adds that the other thing her mother emphasised during these conversations was how much she loved her husband. ‘I'm sure they were terrified,’ Ruth tells us, ‘but they never would have done anything that made me feel insecure.’

This is something Ruth returns to again and again as we talk. By her own admission, Ruth was quite sheltered from the horror playing out in Europe. Otto's parents were murdered in Theresienstadt. His sister and brother-in-law were intercepted in Yugoslavia while trying to flee to Palestine by boat. Ruth remembers her mother's sadness when she received the news about her parents-in-law – she had been close to them. But she says this sadness was not overt. Johanna hid her grief for the sake of her young daughter. This must have been hard for them. Ruth says as a child she would often speak about various members of the family as if she knew them, though she had never met any of these relatives. When we ask if she has any other family in Australia, she says simply, ‘there was no one else’. Her extended family in Europe was murdered. ‘[In those days] everyone in the camp called everyone aunty and uncle,’ Ruth says, remembering the adults she met during her family's internment. ‘So, I had heaps of aunties and uncles, but none of them were “real”’.

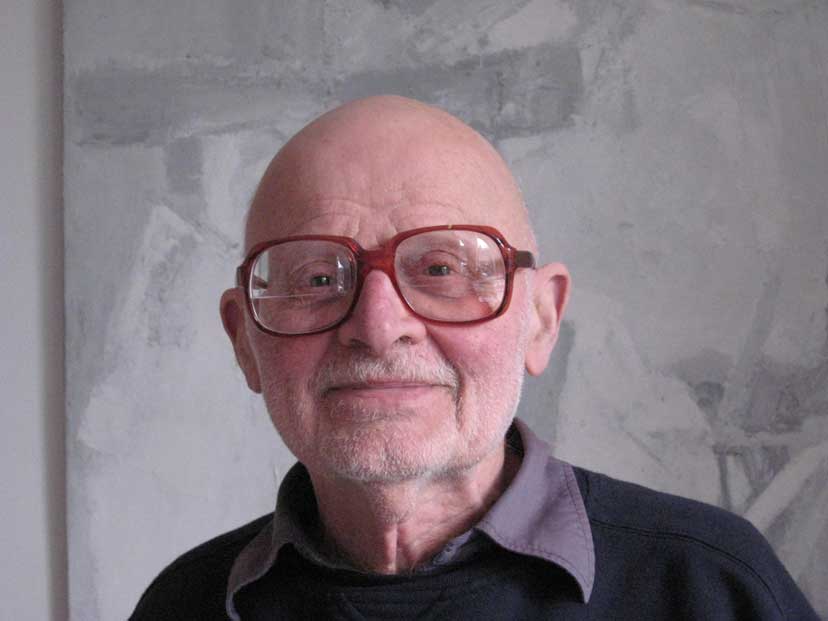

Ruth arrived in Malaya when she was just two years old, so her memories of this time are scant – but a few things stand out. She remembers the sleeping arrangements in the small Dayak village they lived in, her pet monkey Billy, and the terrible bout of malaria that landed her, Otto and Johanna in hospital. With the exception of the malaria, this was a happy time for her parents. Otto was engaged as a civil engineer. People were kind to him and his wife. They were young, and in many ways the whole thing was a big adventure.

Ruth's parents in the camp they lived in British Malaya. Otto, on the left, holds Ruth's monkey, Billy.

Ruth's parents in the camp they lived in British Malaya. Otto, on the left, holds Ruth's monkey, Billy.

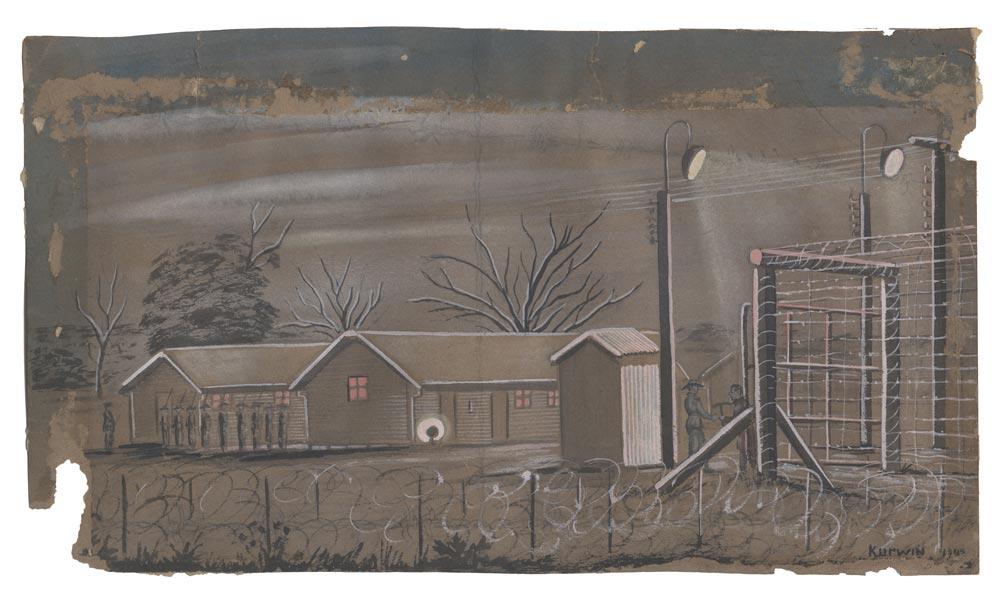

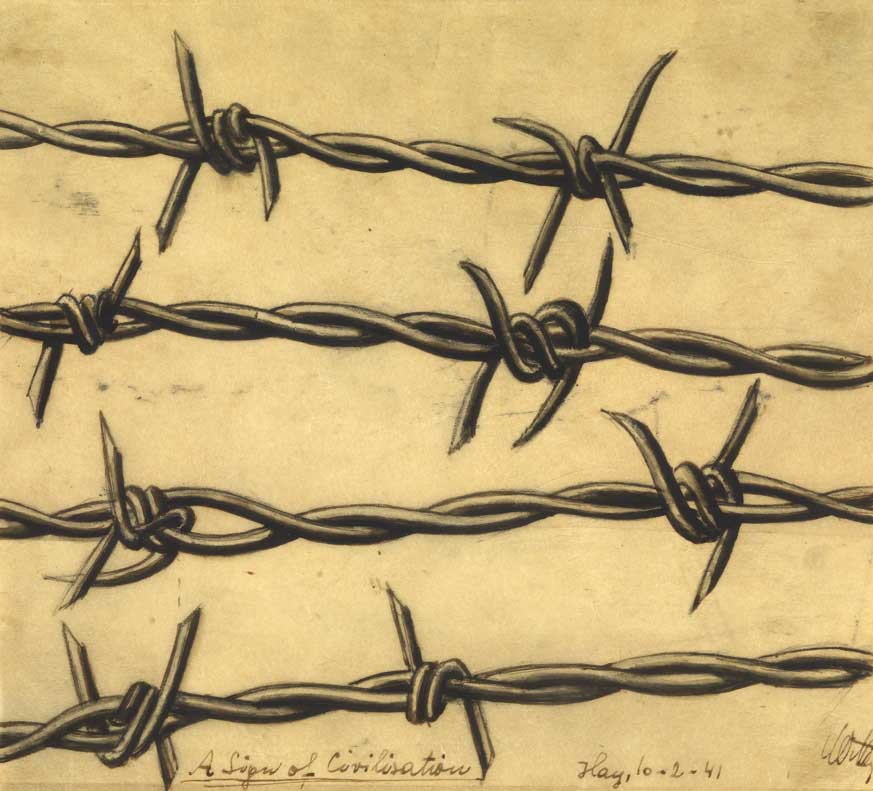

Ruth and her parents were taken to Australia aboard the Queen Mary when she was four years old. Similar to the Dunera internees, they had received a letter requesting that, as ‘enemy aliens’, they present themselves to authorities. They had no idea what to expect. The time her family spent interned at Tatura has left an indelible mark on Ruth's memory, but none of these memories are bad. She remembers the barbed wire, of course, but also the other families and the children she played with. She even remembers receiving a chocolate bar from one of the officers while sitting with her father in the back of the police van on the way to visit Johanna in hospital, after she gave birth to her second child and Ruth's brother, Ron. He was born not long after their arrival in Australia – the first child to be born in the army hospital. The head doctor probably hadn't had to deliver a child in quite some time, Ruth laughs.

As was the case with many of the families that arrived on the Queen Mary, once the father volunteered for the military service his wife and children were released. Ruth and Johanna left the camp in April 1942, two months after Otto joined up. The small family went to live in a bungalow behind a Melbourne home, where Ruth's mother did the cooking and cleaning. Her parents settled into life in Melbourne. They shared their flat with the Fischers, a family they had met in the camp, and made many Australian friends. Ruth grew up as an Australian. She tells us that while her parents had certainly never imagined coming to Australia, initially thinking Malaya already to be far enough away, ‘they always felt extraordinarily lucky’ to have ended up where they did.

Growing up, Ruth says she knew she ‘didn't fit in quite anywhere, but … I don't ever remember anyone being nasty’ – not beyond the odd kid calling her a 'reffo'. Her parents, for their part, remained ever conscious of the high cost of excluding those different from themselves. Ruth recalls a young Greek boy joining her primary school class and being assigned to sit beside her. In her childish innocence, she complained about having to sit next to the new student, only for her father to say, on hearing her new schoolmate's surname, ‘Well, you've got to be nice to him – that's Gottlieb in Greek.’

Ruth's parents placed importance on higher education – for Johanna, it was because this was something that she had never been able to pursue, despite her intelligence. For Ruth, not attending university was never really an option: her father, on hearing that Ruth was interested in becoming a nurse, responded, ‘Why a nurse? Why not a doctor? Or why a draftsman, why not an engineer?’ Ruth went on to study English and German, and had a successful career, and later a family. She worked initially as a share broker's clerk, and later in education, despite the fact that during her studies she had determined that she would never teach.

Johanna and Ruth with one of Ruth's friends in Malaya.

Johanna and Ruth with one of Ruth's friends in Malaya.

Some things have stuck with Ruth from her childhood split across three continents. She grew up speaking German and Italian, and while her language skills have, by her own admission, deteriorated over the years, she continues to chat in German when she catches up with friends – other children of immigrants or refugees. She's always been adaptable when it comes to new situations, and she remembers how affectionate and loving her parents were – with each other and with her. ‘Somebody said to me once, don't you remember the barbed wire in the camp? I said, I remember that, but I remember my mother and father were there. I always felt secure. I think that was my whole thing right through life.’

All photos © Ruth Simon

Author: Kate Garrett