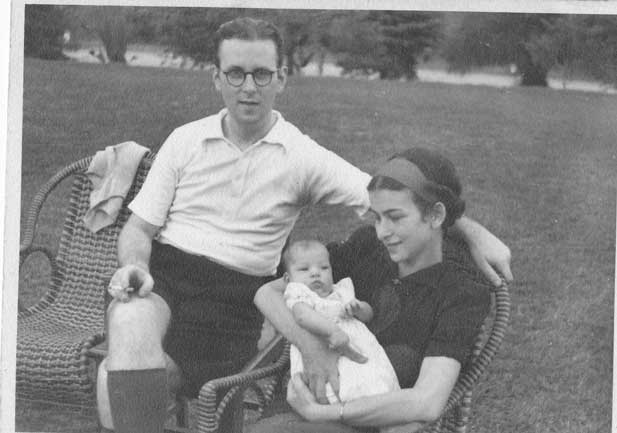

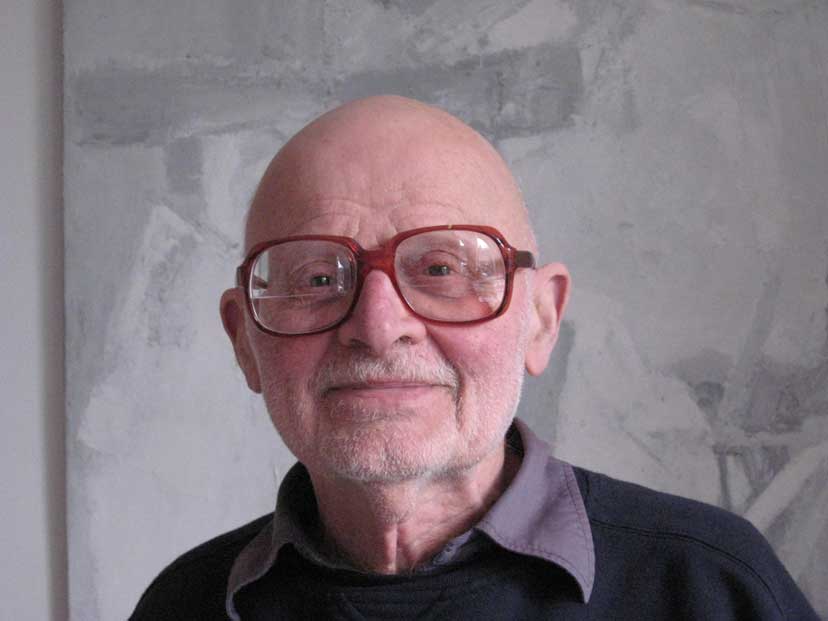

Paul Georg Glass was one of the many refugees interned by the British government at the start of the Second World War and sent to Australia on the Dunera. It can be easy for us – especially as the distance between then and now grows larger – to think of the 74,000 ‘enemy aliens’ interned in Britain in terms of simple numbers, but behind every number is a person with a unique story to be told. This is the story of Paul Glass, a Viennese lawyer and talented artist, who was arrested in England, put on board the Dunera and interned in Australia.

Paul Georg Glass was born in Vienna on 5 September 1891 to Gabriele Gutmann and Max Glass, a consulting engineer, and was raised in the city. Paul’s sister, Alice Margarete, died in infancy. Paul began his university studies at the Law Faculty, University of Vienna, in the winter semester of 1910-11, and finished his degree just before the First World War broke out. He enlisted in the Austrian Army and from 1914 to 1918 fought at the Russian Front with the mounted artillery, operating heavy trench mortars. Paul was decorated for his army service, including with the Iron Cross.

Paul's First World War medals.

Paul's First World War medals.

On 12 March 1919, only four months after the end of the war, Paul received a Doctorate of Law from the University of Vienna, and in 1922 was registered as an advocate, a lawyer, in Vienna. During these years, on 14 February 1920, Paul left the Viennese Jewish community. Later, on documents relating to his internment in Australia, he wrote he was Roman Catholic, although he was raised in a Jewish family. Sometime during or before 1920 Paul’s father Max died.

Paul’s mother Gabriele also left the Viennese Jewish community in 1920, a few months after Paul. Leaving this community could not have been an easy decision for either of them, with the possibility of being cut off from friends, family and community. Paul and Gabriele may have left because of a loss of faith, or a feeling of rejection. Although Gabriele left the Jewish community, she was deemed Jewish by the Nazis who deported her to Litzmannstadt in 1941, a Nazi ghetto established in Lodz, Poland, in February 1940. More than 20,000 Jews from Germany, Luxembourg, Czechoslovakia and Austria, and over 5,000 Roma peoples, were in Litzmannstadt. Gabriele was murdered there on 14 July 1942.

Paul lived and worked in Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s. His law office was on Salztorgasse, in the first district of Vienna and by the Donaukanal; his professional life at the very centre of Austria’s bustling and beautiful capital. The Nazis revoked Paul’s position as a lawyer because he was Jewish, and he fled to Britain. The Austrian official statement records note that Paul left Vienna on 6 December 1939, three months after the start of the war. However, Paul was recorded in the England and Wales Register, 29 September 1939, as living in Hampstead.

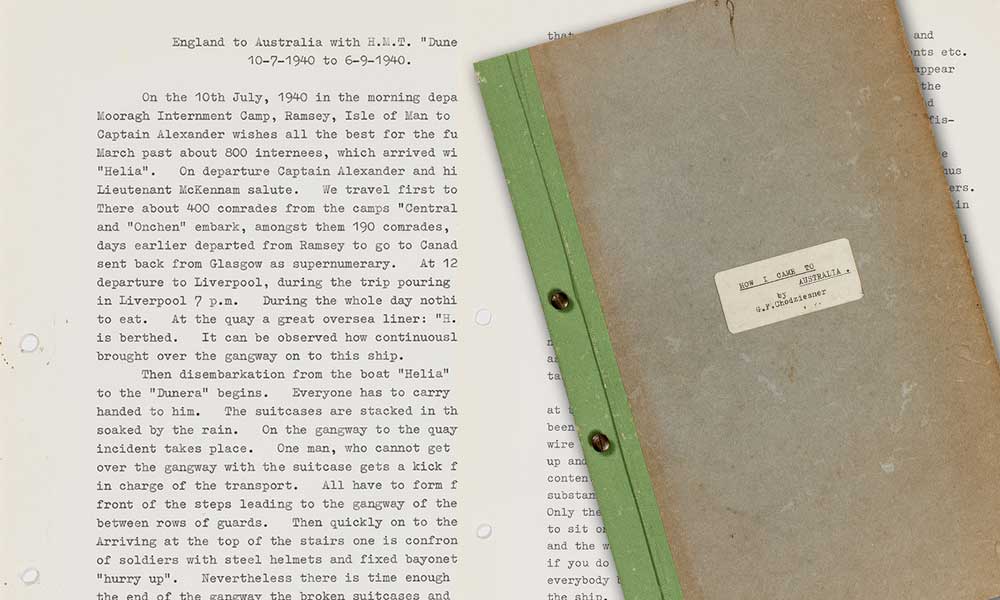

Paul lived in London until he was arrested as an ‘enemy alien’, an Austrian living in Britain, on 2 July 1940. It didn’t matter that Paul had left Austria for fear of being persecuted because of his Jewish heritage. On 10 July 1940, Paul was deported to Australia on the HMT Dunera.

Prisoner of War/Internee Form: Paul Georg Glass. NAA: MP1103/2, E39579.

Prisoner of War/Internee Form: Paul Georg Glass. NAA: MP1103/2, E39579.

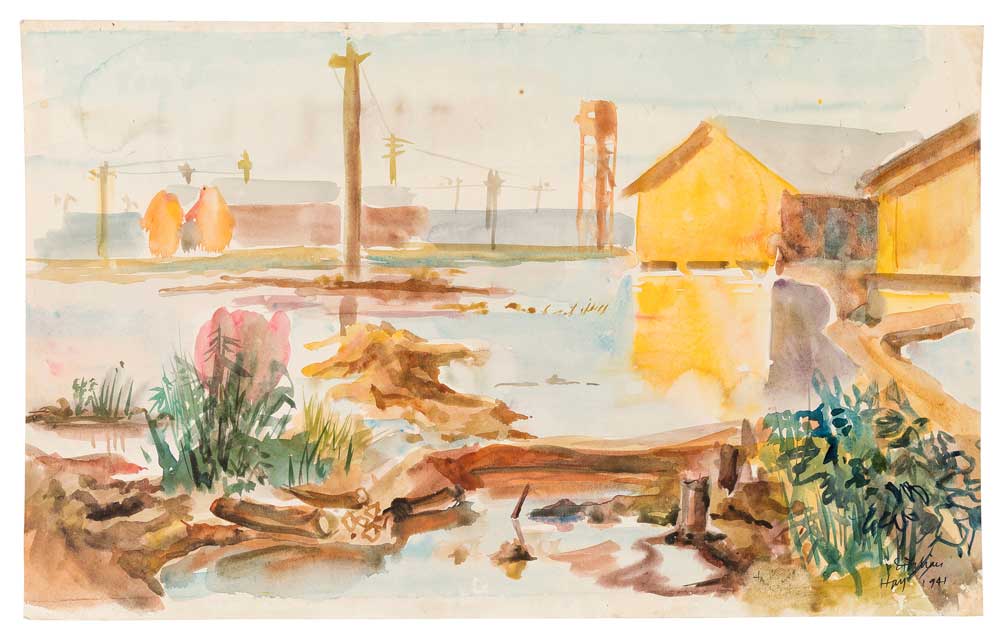

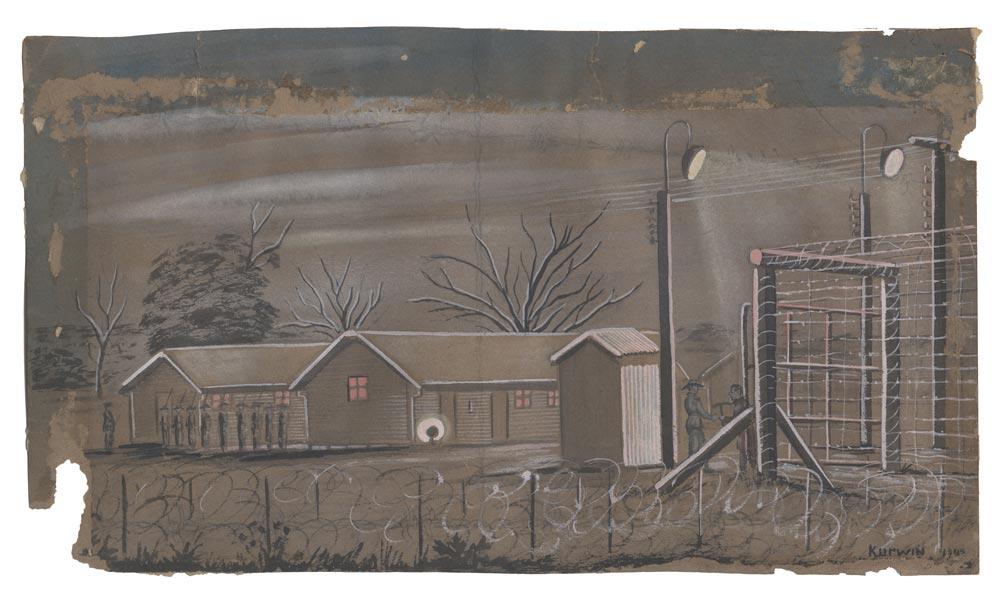

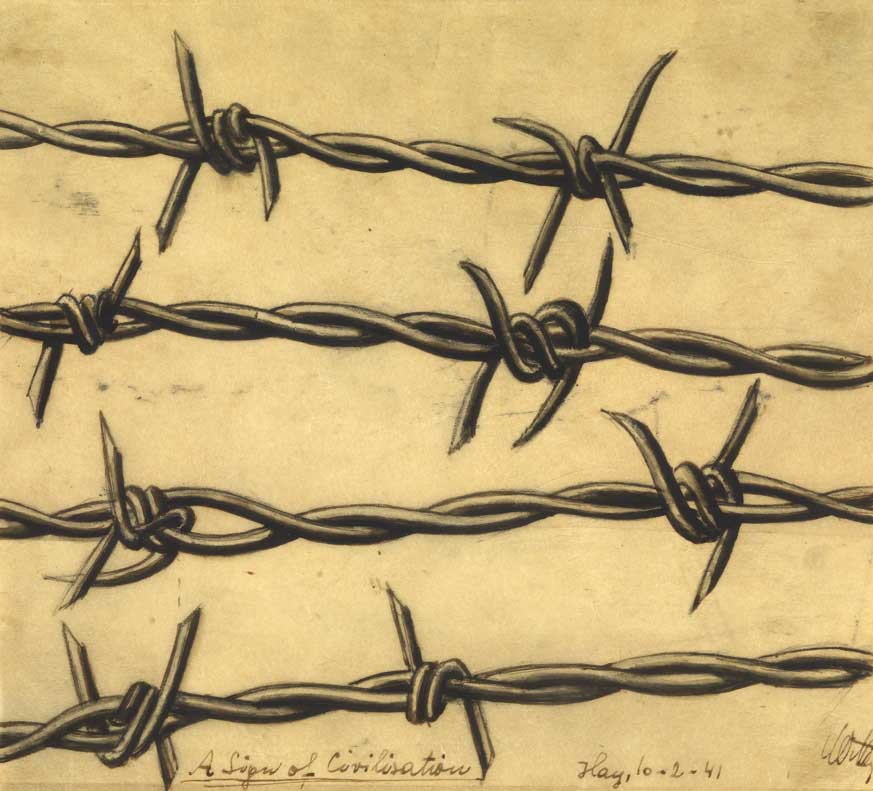

There is little information on Paul’s life during his internment in Australia. He was first interned at Hay, New South Wales, then briefly at Tatura in Victoria. At Hay, he lived in hut 35, Camp 7. He shared the hut with about 21 other men, 16 of whom were Austrian. One of Paul’s hut-mates was the athletics coach Franz Stampfl, who organised various camp sports. George Lederer, who was in hut 26, Camp 7, remembered Paul as an eccentric man with a curly moustache who painted military scenes, including the charge of the Inniskilling Dragoons, on the inside wall of a hut. This must have been a striking mural to stumble on in the sunny Riverina! During his internment Paul produced lots of beautiful art, including a large painted portrait, likely of another internee in the camp. This and other artworks were later found by Valerie Reynolds, Paul’s great niece. In a box of Paul’s keepsakes she discovered also a German translation of a St John Ervine play. She wonders if perhaps it was performed by and for the internees.

Paul left Australia for Britain aboard the SS Ceramic on 15 October 1941. It is unclear exactly why he was released and sent back to Britain. He had been accepted into the British Army Pioneer Corps, but had also been given an unconditional release. Paul married Ena Victoria Glanville at the Registry Office in Westminster on 6 September 1943. Paul was naturalised in Britain through his marriage to Ena, a British citizen. Paul and Ena lived together in London. Valerie believes they lived in Britain until 1947, when they moved to Vienna. Certainly, they travelled from London to Vienna in 1947. Paul was officially reinstated as an advocate in Vienna on 7 October 1946, before this trip. He may have registered with the Austrian legal authorities before his return, or possibly had visited Vienna in the post-war period.

Paul and Ena on their wedding day.

Paul and Ena on their wedding day.

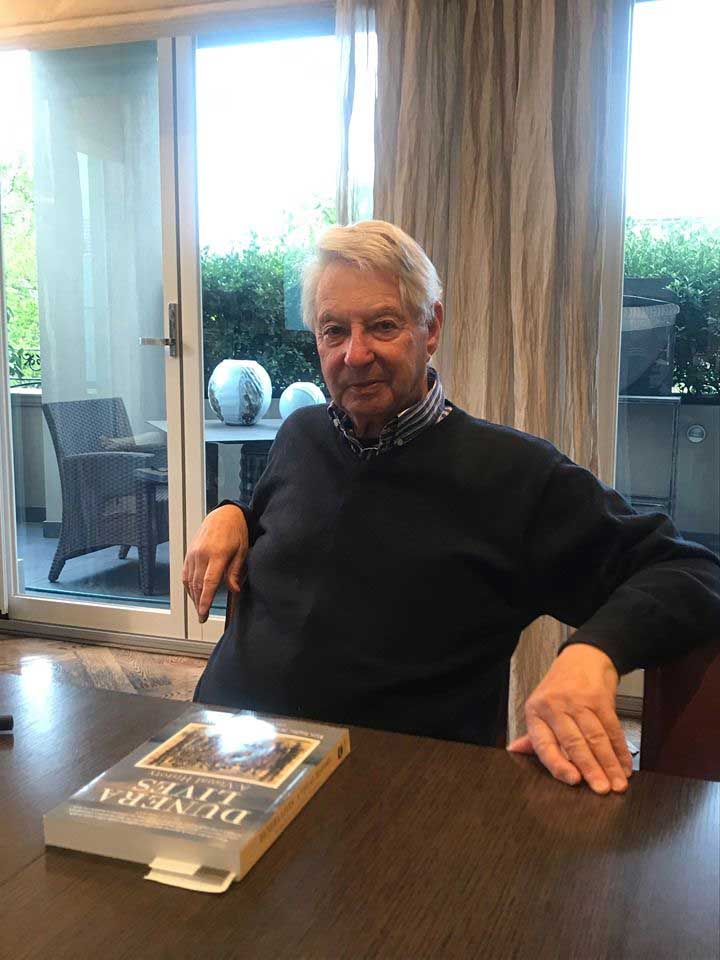

It was unusual for Dunera internees to return to live in Germany or Austria. Potentially there was trauma in such a move. Many felt, understandably, that their country had failed them. Many, including Paul, had friends and family who had been murdered by the Nazis. Some Dunera internees vowed never to return to their homeland, and most chose to start, resume or continue lives elsewhere – in Australia, Canada, the United States, Britain, Palestine/Israel, South America. Paul and Ena lived the rest of their lives in Vienna. Interestingly, five other internees in Paul’s hut at Hay also returned to Austria after the war; perhaps Paul had befriended other men on the Dunera or at Hay who were keen to go home. Much of Paul’s and Ena’s later lives were spent at Liechtensteinstraße 53, also named Palais Kranz – a gorgeous Viennese building located in the 9th district. Paul died in Vienna on 4 September 1962. Ena died in late 1994 or early 1995. They had no children.

Palais Kranz.

Palais Kranz.

In her collection of Paul’s items, Valerie has a treatise he wrote on the history of Tyrol. Tyrol was an Austrian state divided after the First World War when South Tyrol was ceded to Italy. This was clearly a subject Paul was passionate about and his lengthy history must have taken considerable time and effort. Paul was also deeply engaged in supporting Holocaust survivors on his return to Austria. He helped Jewish people recover property that had been appropriated by the Nazis during the war. Perhaps this was the reason he returned?

Paul and Ena in Tyrol.

Paul and Ena in Tyrol.

Paul should be remembered as a fighter, a wonderful painter and a passionate lawyer. Part of his story was in Australia, but he also had a life in Britain, where he married his wife, Ena, and in Austria, where he advocated for the Jewish community. Clearly he felt a strong connection to his Jewish heritage, even if not the religion.

Thank you to Valerie Reynolds, Elisabeth Lebensaft and Carol Bunyan, who have helped me enormously.

All images © Valerie Reynolds

Author: Hannah Robinson