In the years before and during the Second World War, Jewish and anti-Fascist doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists left Nazi-occupied Europe for Australia. Refugee and migrant doctors came to form an integral part of the post-war Australian intellectual landscape, albeit struggling to attain medical certifications that matched the credentials in their home countries.

The internees of the Dunera fit within this broader narrative in diverse and interesting ways. Some men were related to influential psychoanalysts in Vienna and brought their knowledge of Freud to the internment camps in Australia. Others became interested in the workings of the mind after being removed from home, having to make sense of life on foreign soil halfway across the world. These stories are unusual additions to our knowledge of migrant doctors in Australia, adding a rich complexity to our understanding of the internment experience and its global intersections.

Surprisingly, many of these men and women have had their lives documented in newspapers and online with little reference to their time in Australia. There is a puzzling tendency for journalists to skip the years of internment; some erase the period of internment completely. This piece aims to show that the extraordinary minds of these migrant doctors were all, at one time, in the same place under extraordinary circumstances.

A number of internees had been enrolled in British universities when the war disrupted their studies. A register that survives from the internment camp at Hay shows 46 students who were enrolled in studies across England, with four enrolled in medicine.

Psychoanalysis at Tatura

Franz Borkenau-Pollak studied psychoanalysis as a student in Vienna and went on to complete a PhD in history at Leipzig University in 1924. A committed Marxist, he was a member of the Communist Party of Germany from 1921 until his expulsion in 1929 because of differences in opinion regarding Stalinist policies. He left Germany in 1933 and worked in research and political activism in Austria, France and Panama. By 1940 he was married to his wife Johanna and working as a tutor at the University of London when he was captured and deported on the Dunera. Few histories acknowledge Borkenau’s time in Australia, assuming he continued to live in London, working as a writer for the duration of the war.

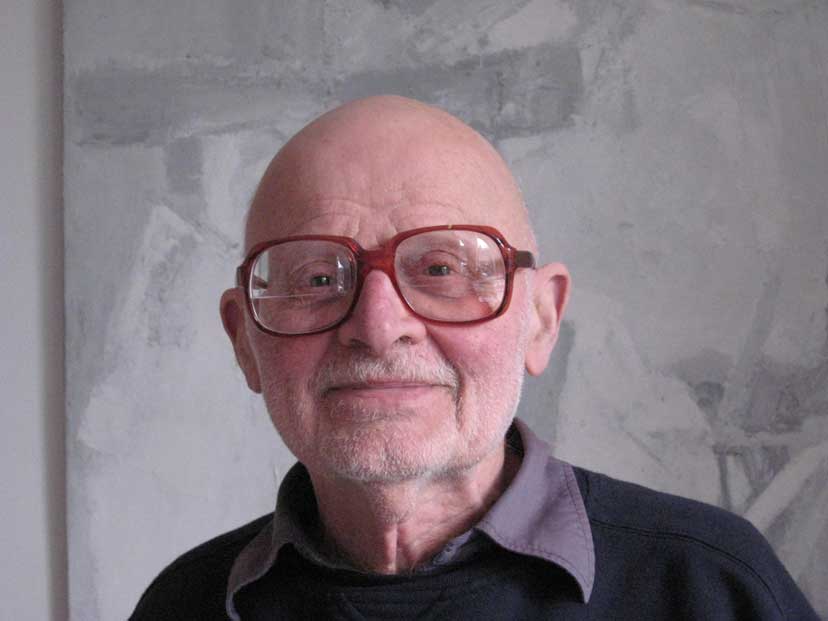

Borkenau gave talks on psychoanalysis to the inmates at Tatura, which one fellow internee recalls as ‘fascinating’. After release, Borkenau returned to Germany to work as a professor in history at the University of Marburg and went on to become a prominent historian and political commentator on Soviet politics.

European Connections

Freud’s grandson: Anton Walter Freud

The most well-known connection to psychoanalysis aboard the Dunera was Anton Walter Freud, grandson to Sigmund Freud. With the help of international connections Anton, Sigmund and other members of the Freud family left Vienna in 1938. Anton was interned with his father on the Isle of Man, before authorities deported Anton on the Dunera.

Anton opted to return to England in 1941 where he joined the Pioneer Corps, transferring to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1943. In an interview with Elisabeth Lebensaft and Christoph Mentschl decades later, Anton Freud expressed his dismay at post-war Austria’s treatment of refugees displaced by Nazism. The Austrian government never requested or invited him to return. Anton remained in England, studied chemistry and worked in that field for much of his life. In the same interview Freud gave the impression that while many people asked him about his famed grandfather, their relationship had always been distant.

Ilmari Federn

Another young man on the Dunera, Ilmari Federn, was the nephew of one of Sigmund Freud’s early associates, Paul Federn. Paul Federn published on the psychoanalytic concept of the ‘ego’, drawing different findings from Freud. Paul’s son and Ilmari’s cousin, Ernst Federn, was a Trotskyist and anti-fascist who after several arrests was incarcerated in Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps over a period of seven years. After the war, Ernst Federn relocated to the United States and published on psychology. Chapters in his volume Witnessing Psychoanalysis detail Federn’s observations of prisoners and perpetrators in Buchenwald, and his conversations with the notable psychoanalyst and fellow inmate Bruno Bettelheim.

Friedrich Fokschaner

More subtle family threads make it difficult to secure information. For example, internee Friederich Fokschaner’s father, Walter Fokschaner, was a member of the Viennese Psychoanalytical Association between 1919-28. He is remembered on their memorial page. There remains little archival trace of him.

After the war

Max Glatt: Tackling alcoholism in post-war Britain

Max Glatt was born in Berlin and graduated from Leipzig University in 1936, earning a doctorate in neurological medicine. After a failed attempt to leave the country in 1938, Glatt was imprisoned in Dachau for a short period before German authorities deported him to England. There he lived freely until he found himself interned in 1940 and placed aboard the Dunera. After almost two years internment at camps in Hay and Tatura, Glatt returned to England. By that time his parents had been killed in Bergen-Belsen Camp.

In his post-war career, Glatt became one of the first psychiatrists to recognise alcoholism as a serious mental addiction requiring medical treatment rather than social condemnation. Glatt lobbied the World Health Organisation to recognise alcohol addiction in the same way as drug addictions. He was successful, and joined the World Health Organisation’s expert advisory panel on drug dependence. He also taught on the subject of addiction at University College Hospital, Middlesex Hospital and Royal Free Hospital.

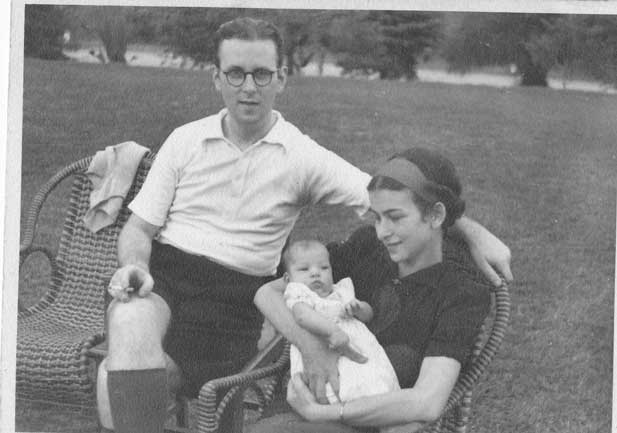

Peter and Nora Huppert

Peter Huppert was qualified as a doctor by the time he was interned, and had intended to specialise in psychiatry. Huppert had migrated from Austria to England in the late 1930s. After deportation on the Dunera and more than a year in camps at Hay, Tatura and Loveday, Huppert took the opportunity to join the Pioneers Corps in Britain. He found employment as a doctor when discharged from service.

In London he met Nora Huppert, a middle-class German Jewish refugee who had left her home in Berlin and reached England, via Prague, on a Kindertransport before the war began. Both her mother and brother perished at Auschwitz. Nora trained as a dressmaker and found work with a dress manufacturing company. She and Peter married in 1951. In the 1960s, they decided to emigrate and make Australia their permanent home.

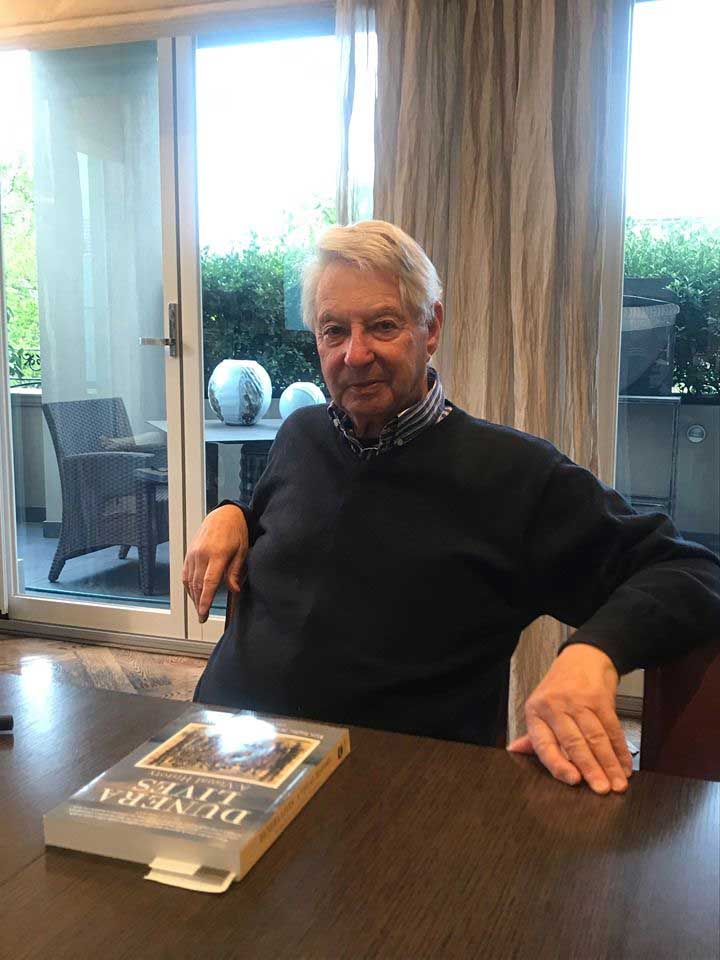

In Australia, the pair devoted themselves to the field of mental health. Peter established a private practice in psychiatry and Nora entered the field of marriage guidance counselling. She would later work at the Australian College of Applied Psychiatry, where there is a student scholarship in her name.

Bela Lindenfeld

Bela Lindenfeld, a Hungarian dermatologist, was married to the psychologist Elda Lindenfeld-Lachs. The Jewish couple and their son escaped Austria in 1939, travelling to England. In 1940 Bela was interned and placed on the Dunera, separating the family. In 1941 Bela was released from Tatura and migrated to Canada where Elda was living. There she published on child and community psychology, and worked with social workers in mental hospitals and in the Department of Public Health in Manitoba. The family moved to Vancouver in 1946, where Elda established a community counselling centre and set up a private practice. The Elda Lindenfeld Memorial Fund continues in her memory.

Edward Trautner

Eduard (later Edward) Trautner served with the German Army in the First World War and in the Weimar years in Berlin was a medical graduate and a fiction writer. He was listed as a member of ‘Gruppe 1925’, a group of 39 left-wing writers and artists which included Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Toller. Forced to leave Germany because of his political writings, Trautner migrated to Spain, then England, where authorities interned him in 1940. His fiancée and her two children followed him to Australia in September 1940, while his wife Marion, a Jewish woman, remained in France. Little is known about the women in Eduard’s life.

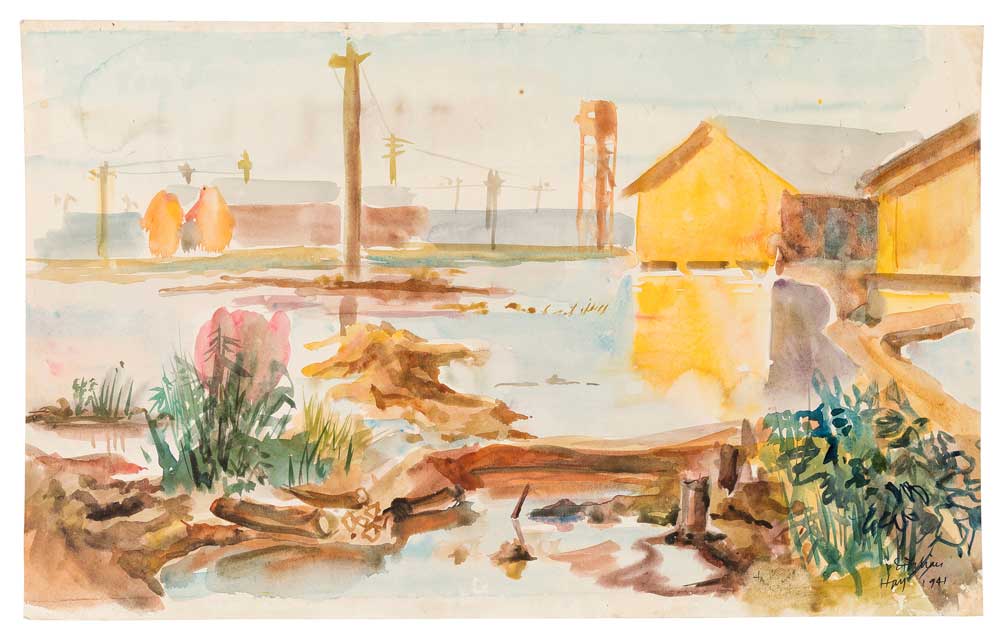

Trautner spent almost two years in camps at Hay, Orange and Tatura from 1940-42. In March 1942 authorities permitted him to leave internment to work in Melbourne, researching the production of synthetic organic chemicals. By 1944 he was living in Altona and had applied for naturalisation; Eduard became Edward. After a trip to Britain, Edward returned to Melbourne in 1948. The Medical Practitioners Registration Act (1946) made it possible for ‘alien doctors’ such as Trautner to register and receive the same recognition as doctors trained in Victoria. Noting Trautner’s work, Professor Douglas ‘Pansy’ Wright invited him to join the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at the University of Melbourne. A report by John Cade in the Medical Journal of Australia in 1949 led to the re-introduction of lithium therapy in psychiatry. However, lithium was not used in hospitals because of its toxicity. In the 1950s, Trautner and a team of associates investigated the use of lithium in clinical settings and issued four reports that contributed to global knowledge of lithium treatment for psychiatric illnesses.

Traces

Less is known of Georg (later George) Dürrheim, who was in his fourth year of study in medicine at the University of Vienna in 1938. A Jewish man, Dürrheim was forced to abandon his studies and moved to England, where he was interned. After release from Tatura in 1942, Georg completed his medical studies at the University of Melbourne. He applied for naturalisation in 1948, and went on to work as a physician in Sunbury and Ararat Mental Hospitals. He married in 1953 in Vienna, and his wife arrived in Australia at the end of January 1954. In the 1960s George and his wife returned to live in Vienna.

Hans Nathanson was a candidate at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute when he was forced to leave Germany. Records indicate he worked in Australia after release from internment, before returning to East Germany to work as a psychologist in homes for neglected children.

After release from internment and service with the 8th Employment Company, Philip Herbst studied psychology at the University of Melbourne and returned to Europe in the post-war period. Herbst went on to pioneer research in industrial psychology, the study of human behaviour and group psychology in the workplace.

References

A big thank you to Carol Bunyan for her research assistance.

Ernst Federn, Witnessing Psychoanalysis: From Vienna back to Vienna via Buchenwald and the USA (London: Routledge, 1991).

Philip Herbst, ‘Foundations for behaviour logic’ Mathematical anthropology 14, 2 (1975); 81-100.

Colleen Ward, Stephen Bochner, Adrian Furnham, The Psychology of Culture Shock (London: Routledge, 2005).

https://individualpsychology.wordpress.com/elda-lindenfeld-lachs/

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2002/may/25/guardianobituaries.drugsandalcohol

https://www.smh.com.au/national/survivor-used-story-to-teach-others-20121105-28tz3.html

Author: Georgina Rychner