Before he was a world famous fashion photographer, Helmut Newton was interned at Tatura as a German-Jewish refugee.

Karl Lagerfeld, in writing of the life of Helmut Newton, describes the years the famous photographer lived in Australia as ‘mysterious and unknown’. Though Lagerfeld wrote this while Newton was still alive, it would seem that collective amnesia regarding Newton’s internment in Australia during the Second World War endures after his death.

The multitude of articles and reviews written over the course of the photographer’s life usually omit any detail of his Australian years, touching on Newton’s early life in Berlin before focussing on his return to Europe at the beginning of his career in fashion photography. Guy Featherstone’s research into Newton’s experiences in Australia is a rare exception.

This silence prompts wonder about how Newton remembered his internment. To what extent did this period influence his photographs, his settings and his self-expression? His various interviews suggest that he was not a man to dwell on the past. Lagerfeld, who met him several times, had the same impression. He described the way in which Newton was not interested in perfecting a style and sought to avoid professional stasis; he moved forward, pushing up against the next boundary. His was ‘a talent that never looks back in time’.

Newton, then Helmut Neustaedter, was interned in Tatura, Victoria, on his arrival in Australia in September 1940. He had been raised by German-Jewish parents in Berlin, and while they were not strict in observing Jewish customs, they frowned upon an early Aryan girlfriend. Helmut did not tell them when he dropped out of school at the age of sixteen to work as an apprentice for the photographer Else Neulander Simon.

Newton’s budding career was interrupted by the rise of the Nazi Party. His father, a button manufacturer, spent time in a concentration camp before managing to escape to Chile with Newton’s mother. Simon, known to many by her professional pseudonym Yva, was forced to work as a radiographer before the Nazi regime ordered her deportation to Madjanek concentration camp; she was murdered in 1942. Helmut, then eighteen, secured a ticket to Trieste and there boarded a ship for China. As it was, he disembarked in Singapore where he worked as a reporter and photographer. In September 1940, authorities identified him as an ‘enemy alien’ and ordered his deportation to Australia.

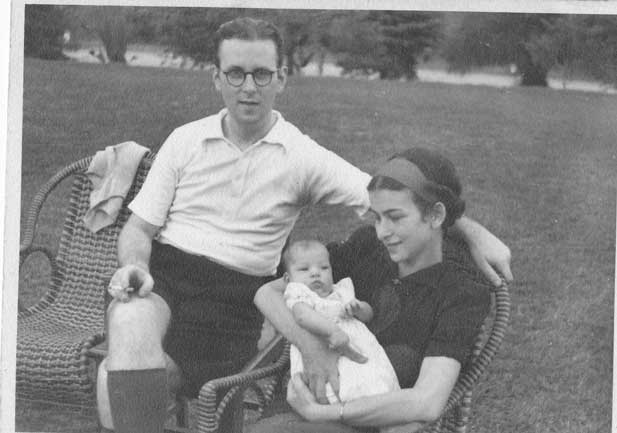

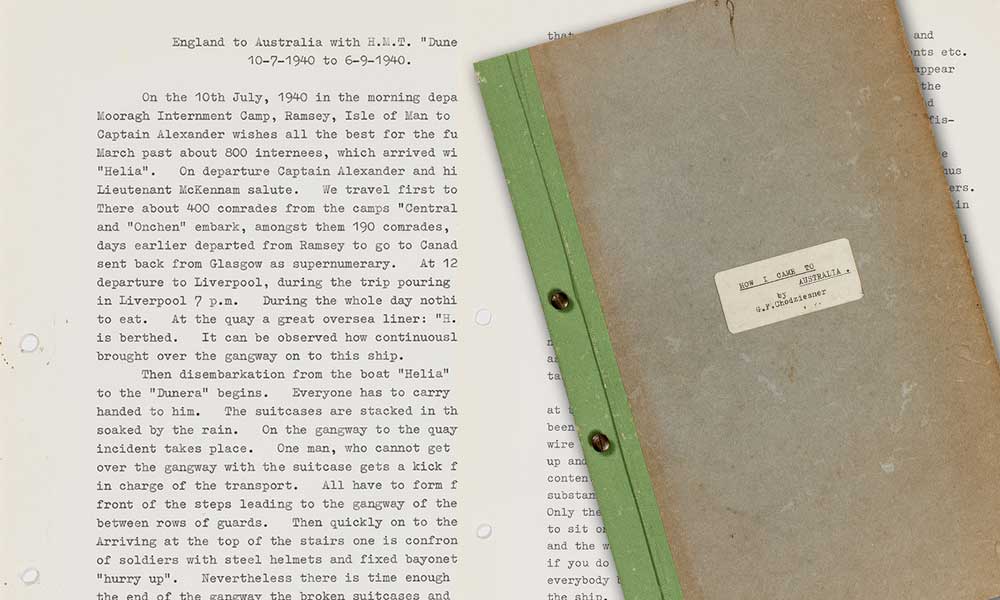

The Queen Mary was an ocean liner that the British requisitioned as a troop ship during the Second World War. In 1940, she carried 266 men, women and children to Australia where they were to be interned for the duration of the war. Though the Queen Mary carried out the same duty as the HMT Dunera in transporting ‘enemy aliens’ to Australia, the internees on the Queen Mary were considerably more comfortable. Newton shared the voyage with other escapees from Hitler’s Reich, the Duldig and Baer families among them.

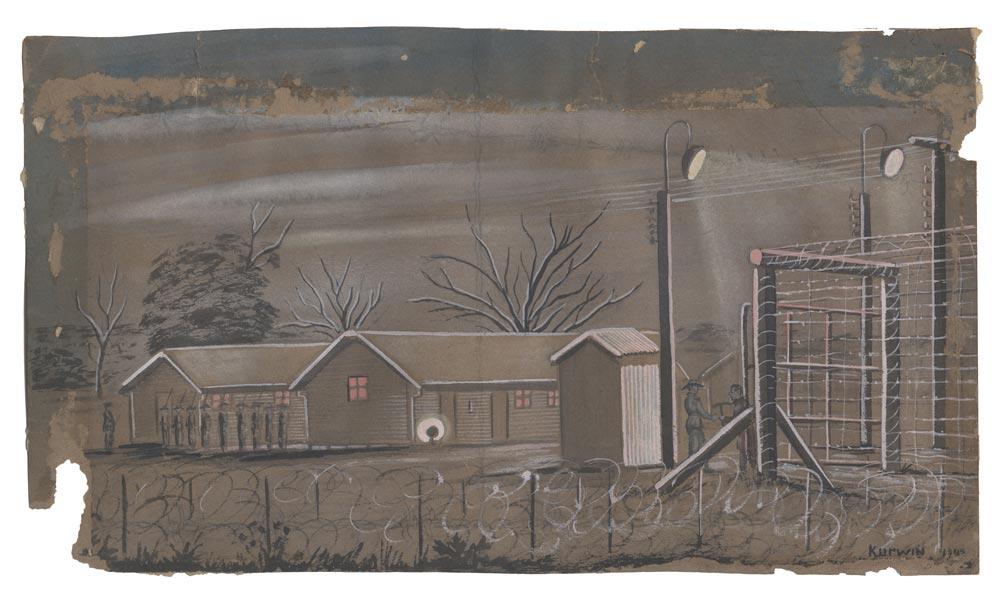

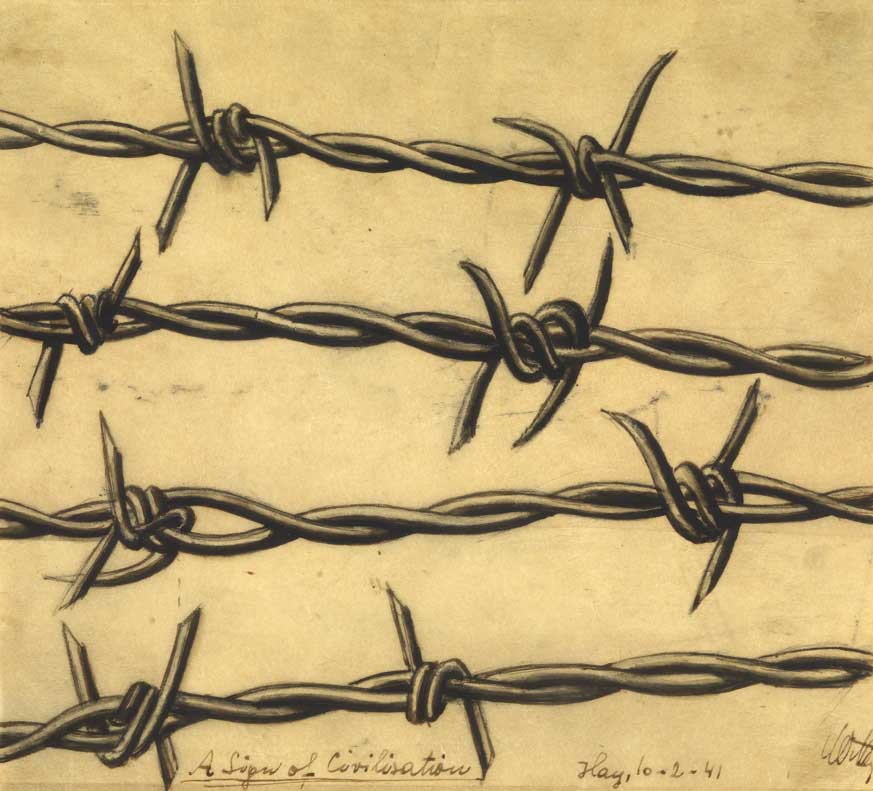

The Queen Mary internees arrived at Tatura in September 1940. Initially, they were placed in Camp 3; married couples, children and single women were separated from the single men. Life dragged on in Tatura. Newton volunteered for latrine duty, an unpleasant job but one that lasted only a few hours each morning and freed the rest of his day. Newton contributed to the intellectual culture at Tatura by teaching photography. The few photographs that capture the lives of internees – generally, cameras were forbidden in internment camps – originate from the Queen Mary camp.

One of Newton’s pupils was Bern Brent, who had been transported on the Dunera at the age of seventeen. Brent recalls that he and Newton met properly when Newton noticed a photograph mounted in Brent’s hut. Newton recognised the unique mounting of the image as the hallmark of none other than Yva, his boss in Berlin. Brent told him that he had received the photograph from Gaby Weyl, a photographer and a colleague of Newton’s at the studio where he had worked as a teenager.

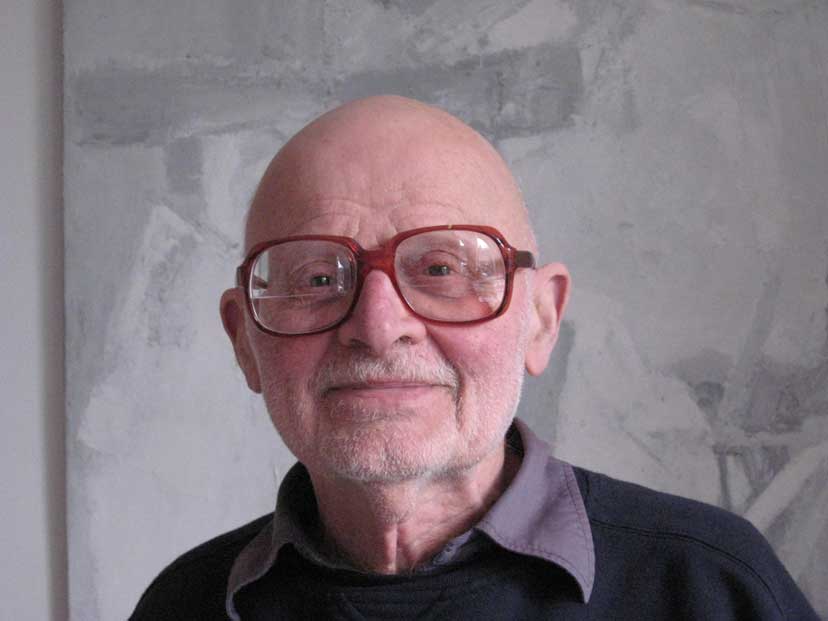

A photograph taken in the 1940s. Newton stands at the back of the line with his hands on his belt.

A photograph taken in the 1940s. Newton stands at the back of the line with his hands on his belt.

Newton joined the 8th Employment Company in 1942. After three months fruit-picking, he donned a uniform and joined the army. Brent recalls that, one morning, the conversation among the ranks turned to ‘Quislings’, or the governments sympathetic to fascism in wartime Norway. ‘Quislings?’ Newton called out. ‘We are all Quislings!’

Newton was discharged from the Army in 1946. That same year he was naturalised, and changed his name from Neustaedter to Newton. Between 1946 and 1948 he rented a small studio on Flinders Lane and scraped together a living shooting clothing catalogues, one of which included the ‘Hat of the Week’ feature for Myer department store, with actress and model June Browne. June and Helmut were married in May 1948, heralding the beginning of their entwined creative careers. Browne reached the height of her acting career in the Melbourne theatre scene during the 1950s.

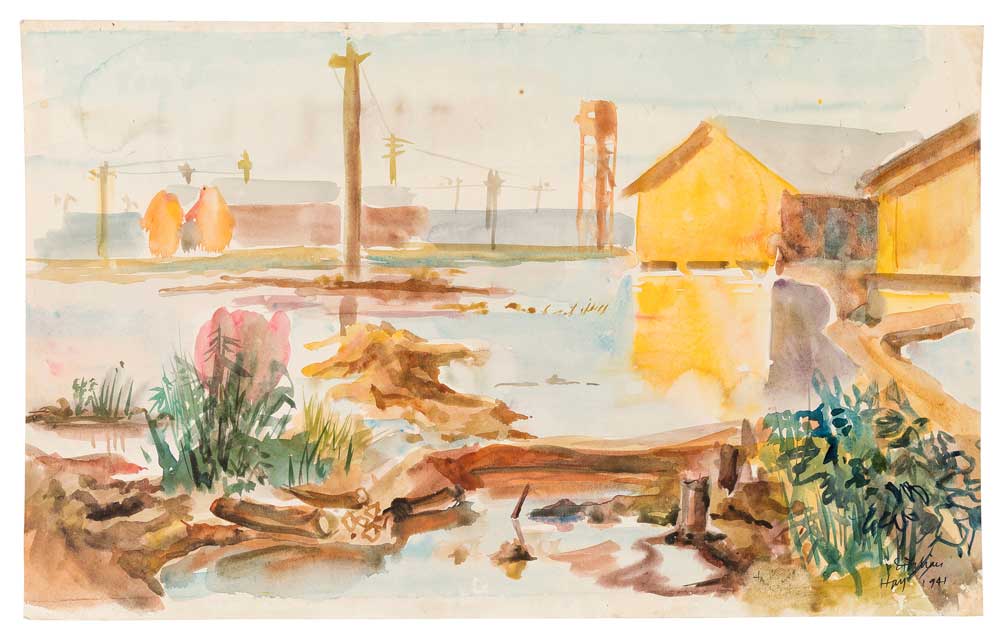

A small, inauspicious exhibition at the University of Melbourne in 1950 hosted Newton’s images. However, the work that paid in the booming post-war economy was industrial. Newton worked at the Shell Company in Geelong from 1951 to 1956. He was employed to take photographs of the construction process, capturing picks, shovels and the ‘everyday’ of men at work. A catalogue advertising Shell products shows Newton’s photographs: a slight nod to the fashion photography he would become known for.

Shell paid the bills, and in 1953 allowed Newton to show his works with fellow refugee Wolfgang Sievers in an exhibition titled ‘New Visions in Photography’ at the Federal Hotel in Collins Street. The Age remarked that this exhibition was to be the first of its kind’ in Australia, introducing the ‘New Photography’ of 1920s Europe to post-war Melbourne. Through exposure and work with some of Melbourne’s most well-known models, Newton began to make inroads into the fashion industry and feature more prominently in print style sections. The year 1956 saw the end of his work with Shell, the opening of a joint-studio with fellow Tatura internee Henry Talbot (Heinz Tichauer), and the chapter where Newton’s biographies usually begin: his contract with Australian Vogue and subsequent employment by British Vogue. In 1957, June and Helmut left Melbourne for London.

The rest of Newton’s and Browne’s careers are well documented. Newton’s photography for Vogue elevated fashion photography beyond clothes and accessories; his photographs placed his model at the centre, creating a cool mood of distance and foreboding through her pose, her expression and often, her unapologetically naked body. His career took him to Paris, Salzburg, New York, Los Angeles. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, he took the portraits of style icons and European royalty: the only clients who could afford his charge of $14,000 per shoot. His subjects included Karl Lagerfeld, Gianni and Donatella Versace, Angelica Houston and Brigit Nielson. A heart attack in 1971 saw Newton with a newfound appreciation for life, selling his Paris and Los Angeles homes to settle with June in Monte Carlo.

A couple of years later, when Newton was nursing a cold, June showed up for a photography assignment for which her husband had been contracted. With this chance encounter her own career as a photographer began. The couple agreed that to use the name June Newton would be too much of a risk, should her photography flop. In deliberating over a professional pseudonym at a dinner party, a Spanish film producer said ‘You must be Alice Springs. It’s a delicious name, isn’t it?’ And so Alice Springs was born. She would receive high acclaim for a photo, often wrongly credited to Newton, depicting a model with a hitched skirt walking down the Champs-Elysees.

The historian Klaus Neumann marvels at the number of newspaper articles and obituaries that document Newton as having worked in Singapore before ‘settling’ in Melbourne. But for the research of Neumann and Featherstone, little would be known of Newton’s past as an interned refugee. (An ‘autobiography’ covering his time in Australia was published posthumously in 2003, but it is uncertain how much of it was written by Newton.) His story remains firmly grounded in his European roots, and European was how he presented himself. Post-war Europe allowed him to pursue the experimental and the provocative where conservative Melbourne did not.

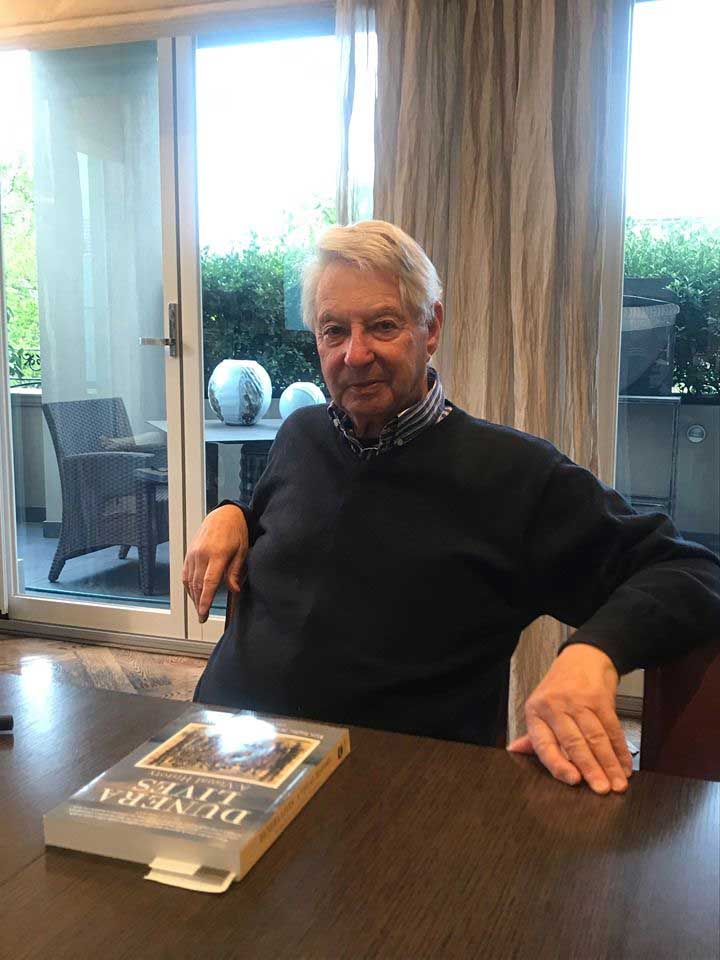

Taken in the 1940s, in this photo, Newton sits second from the right.

Taken in the 1940s, in this photo, Newton sits second from the right.

The lack of memory (and interest) regarding his Australian years is seemingly a product of his own cultivation. In 1989, a Sydney Morning Herald journalist lamented that Newton ‘refused point blank to discuss why and how he made his way to Singapore and hence to Melbourne’. ‘It’s a long story’, Newton reportedly said. ‘We won’t go into that. Everybody knows I’m Jewish.’ When he changed his name in 1946, he swore ‘to never think of himself as Neustaedter again’. Yet the young photographer did not renounce those roots altogether, as shown in his partnerships with fellow German refugee artists in the post-war years. Perhaps the best way of understanding the artist’s time in Australia is through his own words: ‘they were formative years, but they didn’t form me.’

All images © Bern Brent

Author: Georgina Rychner